The rescue of 438 people by the MV Tampa on 26 August 2001, and its boarding three days later by Australian special forces after its captain had defied a government order not to enter Australian waters, are widely seen as a pivotal moment in Australian history. The ABC identified the day of the vessel’s arrival in Australian waters as one of “eighty days that changed our lives.” The Conversation selected it as one of ten “key moments in Australian history.” The Guardian called the Tampa “the ship that capsized Australia’s refugee policy” and Amnesty International referred to the incident as “the single most important moment in the history of Australia’s response to refugee arrivals.” It is the topic of the final chapter in the 2008 book Turning Points in Australian History.

This and similar claims are based on five enduring myths:

Myth #1: The Australian government’s response to the Tampa determined the outcome of the November 2001 federal election.

No doubt, the government’s handling of the Tampa’s arrival persuaded many of those who three years earlier had voted for Pauline Hanson to return to the Liberal–National fold. But pre-election polls and analyses of the 2001 Australian Election Study strongly suggest that the 9/11 terrorist attacks played a greater role in the re-election of the Howard government.

Myth #2: The Pacific Solution and Operation Relex constituted a radical departure from Australia’s established asylum seeker policies.

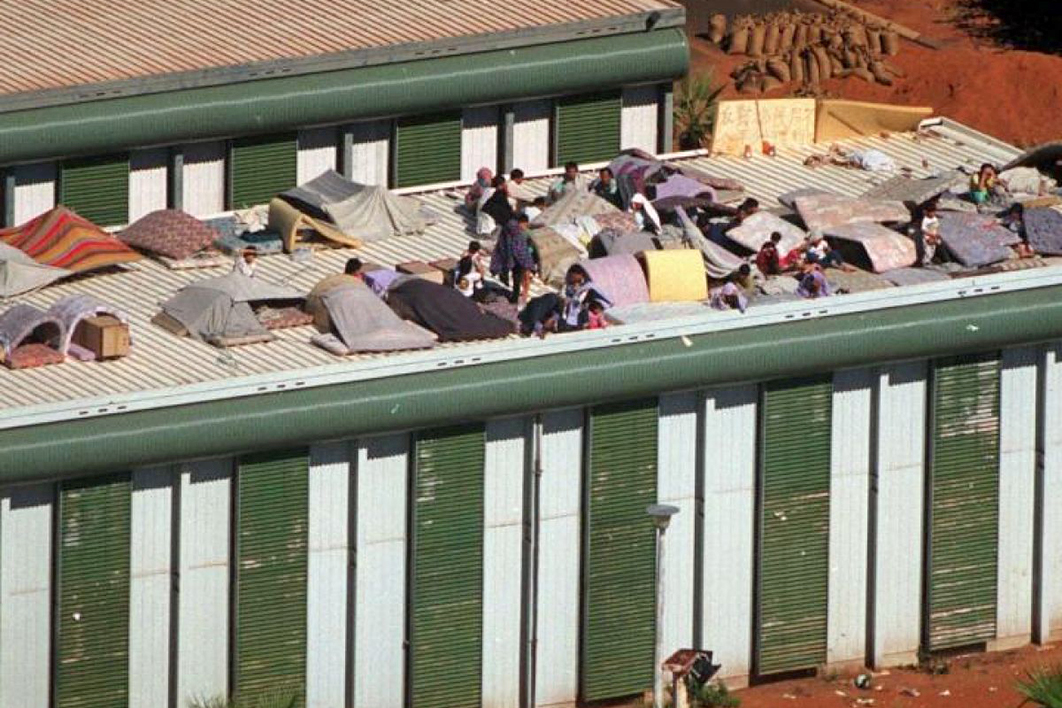

The introduction of extraterritorial incarceration and processing as part of the Pacific Solution and of pushbacks during Operation Relex were indeed new. But they followed a long succession of ever more draconian measures to punish people who had sought Australia’s protection, including the introduction of temporary protection visas and the isolation of asylum seekers in remote camps. Extraterritorial incarceration and pushbacks were simply the logical extension of policies of exclusion and deterrence that went back at least to the Keating government’s introduction of mandatory detention nine years earlier, if not to the Whitlam government’s resolve in 1975 to disembark Vietnamese boat arrivals into custody to be able to return them to their boat “for the purpose of departing them from Australia.”

Myth #3: The Pacific Solution and Operation Relex were innovative responses to irregularised migrants, in Australia and internationally.

The government’s response was not unprecedented. Other states had tried, sometimes successfully and sometimes not, to prevent refugees and other irregularised migrants from entering their territory by deporting them to places where they were out of sight and beyond the reach of supporters and domestic courts. In 1940, Britain deported more than 1500 Jewish refugees who had tried to settle in Palestine to the British colony of Mauritius, where they were detained for several years at the Beau Bassin prison. The British government toyed with a similar approach in 1972, when it briefly considered deporting people of South Asian ancestry, who had been expelled by Uganda’s Idi Amin, to the Solomon Islands.

But Australian policymakers in 2001 probably looked for inspiration not to Britain but to the United States, and to its policy of interdiction, in the 1980s, and then of interdiction and offshore detention, in the early 1990s. This policy was mainly directed at Haitians trying to reach the American mainland. From 1991, those interdicted by the US authorities in the Caribbean were incarcerated at the Guantanamo Bay naval base.

Myth #4: Australia’s response to asylum seekers in the wake of the Tampa’s arrival has served as a blueprint for European asylum seeker policies.

Over the past twenty years, the Australian government has promoted its “solution” in Europe, with senior bureaucrats regularly trying to convince their European counterparts of its advantages. In some instances, the arguments were well received.

Some European politicians have tried to persuade their governments and the European Union to establish processing and detention facilities in other countries. Advocates of policies reminiscent of the Australian approach have included, among others, the German interior minister Otto Schily, a Social Democrat who in 2004 proposed to establish extraterritorial camps for asylum seekers, and the Danish Social Democrats, who since 2018 have sought to introduce laws to transfer all asylum seekers arriving in Denmark to a third country.

Pushbacks, too, have occurred at the European Union’s external borders, most recently in Poland, Croatia and Greece. And on 1 December, the European Commission put forward proposals for a temporary suspension of established asylum procedures at the borders of Lithuania, Latvia and Poland.

But although currently all European governments bar three —Germany’s, Portugal’s and Luxembourg’s — would like the European Union to adopt harsher measures to stop prospective asylum seekers from reaching Europe, Australia’s response has thus far not been emulated. This is because European governments are bound by domestic and European refugee and human rights law that prevents them from copying outright Australia’s flouting of international law. Or at least, it means that when European governments do violate the rights of irregularised migrants, they risk being called to account, if not in domestic courts, then in the European Court of Human Rights. In 2012, for example, the court found in the landmark Hirsi case that Italy had violated European law by turning back some 200 Somali and Eritrean irregularised migrants to Libya.

In Australia, by contrast, the absence of constitutionally enshrined human rights has allowed the government to introduce legislative changes whenever domestic courts, including the High Court, have objected to the country’s punitive asylum regime.

It’s worth noting that those who want European governments to follow the Australian example all the way tend to belong to the far right. Katie Hopkins, rather than Otto Schily, is representative of those suggesting that the Australian “solution” ought to be copied. From a European perspective, the Australian government’s response to irregularised migrants arriving by boat is extremist — and baffling even for many of those on the political right.

Myth #5: The cruel treatment of asylum seekers in Nauru and on Manus effectively deterred potential sea-borne arrivals.

The policies of deterrence caused great harm to the detained asylum seekers, were extremely costly — and were largely ineffectual in terms of their ostensible aim. Boats with asylum seekers continued to arrive after those rescued by the Tampa had been deported to Nauru. But the Howard government must have known that deterrence on its own does not work, since it had tried for several years and without much success to deter prospective asylum seekers by turning detention centres on the Australian mainland into veritable hell-holes. It was only when customs and navy ships physically prevented asylum seekers from reaching Australia that the boats stopped coming. Similarly, it was the Abbott government’s Operation Sovereign Borders, rather than the reopening of Nauru and Manus, that persuaded irregularised migrants of the futility of boarding a boat bound for Australia.

But the policies of deterrence were also successful in that they served to appease an anxious Australian public. And arguably that has been their main rationale all along.

The Tampa affair is nevertheless extraordinarily significant — not because it represented a turning point back then, twenty years ago, but because of how it has been remembered — indeed because it has been remembered as a turning point.

Turning points in history — the storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1789, for example, or the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on 28 June 1914 — are seemingly singular events. In the most extreme case, that event is reduced to a single shot, as if the broader context were a distraction that needed to be blotted out. Thus the fact that Gavrilo Princip killed not only the Austrian heir presumptive, but also his wife Sophie, has been largely erased from collective memory. Even more important, what happened before becomes part of an amorphous pre-history that cannot compete with the era heralded by such pivotal events.

The focus on a singular event is problematic when we try to understand what caused the first world war, for instance. But it is even more problematic when the significance of a particular event is overstated.

Because we remember the moment the Tampa sailed into Australian waters as a new beginning that delineated a pre-historical past from our present, we tend to forget that pre-2001 policies of exclusion reach back to the early days of the Australian nation-state. We also tend to pay too little attention to the history of mandatory and potentially indefinite immigration detention that began under the Labor government in the early 1990s.

We don’t remember that in the 1960s Australia pushed back refugees from Indonesian-controlled West Papua across the border of the Territory of Papua and New Guinea without allowing them to lodge an application for protection, and that those who were permitted to remain in the Australian territory were only given temporary protection visas. We don’t remember that some of those permissive residents were isolated in a camp on Manus in the late 1960s.

We don’t remember that the mantra “we will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come,” far from being invented by John Howard, consistently accompanied twentieth-century Australian politics. In 1934, for example, Robert Menzies, then attorney-general in the Lyons government, declared in parliament: “We have, as an independent country, a perfect right to indicate whether an alien shall or shall not be admitted within these shores.”

We don’t remember that the 2001 election campaign was not the first in which a major party tried to appeal to, and stoke, Australian fears of seaborne arrivals. In 1977, the Labor Party tried to use the spectre of Vietnamese “boat people” to gain an electoral advantage. It was then that the term “queue jumper” made its first appearance, employed by none other than Gough Whitlam. Labor’s scare campaign was unsuccessful — but who is to say that Howard would have been successful in 2001 if it hadn’t been for the threat of terrorism?

The Howard government’s response to the Tampa is widely considered a cynical ploy to win the November 2001 election. The decision to board the Norwegian container ship may indeed have been informed by the government’s poor performance in the polls. But there is more to the Tampa affair’s historical context than the Newspoll results of July and August 2001.

That context also includes the screening of the Four Corners documentary “The Inside Story” on 8 August. It showed footage shot with a camera smuggled into the Villawood detention centre. The footage, which featured Shayan Badraie, a deeply traumatised Iranian child, had a huge impact at the time, and immigration minister Philip Ruddock was initially unable to say anything that would counter it. The government risked losing control of the narrative about asylum seekers and border protection. The response to the Tampa — and, even more so, the children overboard affair — were also attempts to regain that control.

The Tampa affair has been significant because the five myths that surround it have been so enduring. The idea that the Tampa’s arrival decided the 2001 election has served as an excuse for Labor to go along with the Coalition’s policies for most of the past twenty years. Maybe key Labor leaders really have been convinced that asylum seekers are always foremost on voters’ minds when they cast their vote; certainly this “myth that grips a nation” has allowed Labor leaders who are comfortable with the Coalition’s border policies to say that they would have adopted a different stance but could not because it would have resulted in electoral suicide.

If the boarding of the Tampa by Australian special forces on 29 August 2001 was not as significant an event as is commonly assumed, then it makes sense to ask: was there anything else, in terms of Australian responses to migrants in general and refugees and asylum seekers in particular, that was more significant?

Yes, there was. Here is my selection of six days that shaped the nation.

The most pivotal date is 1 January 1901, the day the Australian Constitution entered into force — not because of what the Constitution says, but because of what it does not include: a bill of rights. Australia’s lack of such an instrument has determined not only refugee and asylum seeker policies but also the public discourse about these policies.

Australia embarked on a particular trajectory right after Federation, with the passage of two pieces of legislation on 12 December 1901: the Pacific Island Labourers Bill, which provided for the deportation of Pacific Islanders who had been brought to Queensland as indentured labourers to work on the cane fields, and the Immigration Restriction Bill, designed to ensure that only Europeans would migrate to Australia, which became the legal cornerstone of the White Australia Policy.

These were not the only pieces of legislation intended to deport certain Australian residents and exclude particular groups of prospective immigrants. The Labor Party’s first major contribution was the Wartime Refugee Removal Act 1949, which provided for the deportation of non-European refugees brought to Australia during the second world war, regardless of whether they had Australian families. And then, of course, came the numerous amendments to the Migration Act under Labor and Liberal prime ministers over the past thirty years.

The introduction of mandatory detention was another key moment. But the Migration Amendment Act 1992 was but one of many legislative changes designed to ensure that unwanted arrivals could be detained and then deported. So let me opt for another, less well-known piece of legislation that predated the introduction of mandatory detention: on 21 June 1991 parliament passed the Migration Amendment Bill 1991, which allowed the authorities, among other things, to indefinitely detain one particular individual: a Cuban refugee it had deported earlier that year but had to accept back into Australia because no other country was willing to take him.

But Australia’s response to forced migrants has been contradictory — and that too is often forgotten when we imagine Australian history as going one way until August 2001 and another way thereafter. Here are three dates that could anchor an alternative narrative: On 22 August 1945 Arthur Calwell — the same Calwell who was later responsible for the Wartime Refugee Removal Act and who in 1972 objected to Australia’s accepting a handful of refugees from Uganda because they had the wrong skin colour — decided that Jews who had survived the Holocaust and who had relatives in Australia were welcome to settle there even if they did not meet the usual entry requirements.

On 19 June 1975 Gough Whitlam — the same Whitlam who did not want Vietnamese “boat people” to enter Australia because they were supposedly jumping a queue — announced that Australia had selected Vietnamese refugees in Hong Kong for resettlement. What he did not say was that this selection represented a new beginning because for the first time Australia took in refugees foremost on humanitarian grounds.

On 29 July 2008 then immigration minister Chris Evans gave a talk at the ANU in which he outlined the Rudd government’s far-reaching changes to the way it would respond to asylum seekers. Admittedly, these changes were shortlived. But they are worth mentioning, not least to debunk the idea that our present began in August 2001 and has seamlessly continued since the day the Tampa appeared off Christmas Island. •

This is an extended version of a talk delivered on 2 December at the 2021 Australian Historical Association conference.