After the next election, whatever the outcome, major party campaigners will showcase their prowess, explaining to journalists how they “saved” these electorates and/or heroically “snatched” others. They’ll usually neglect to mention the personal-vote dynamics that led them to prioritise those seats in the first place.

What’s a personal vote? It’s the small level of support that attaches to any House of Representatives MP simply because they are the sitting member. A per cent or several of the electorate will vote for that person because they know their name, or have seen them at events, or in the local paper, or perhaps in parliament on the nightly news.

It’s conceptually simplest in the two-party contest, and is best estimated, or at least identified, after a change. When an MP retires (or is forced out) support for his or her party slumps a bit in that seat relative to the rest, or at least relative to surrounding electorates and/or similar electorates.

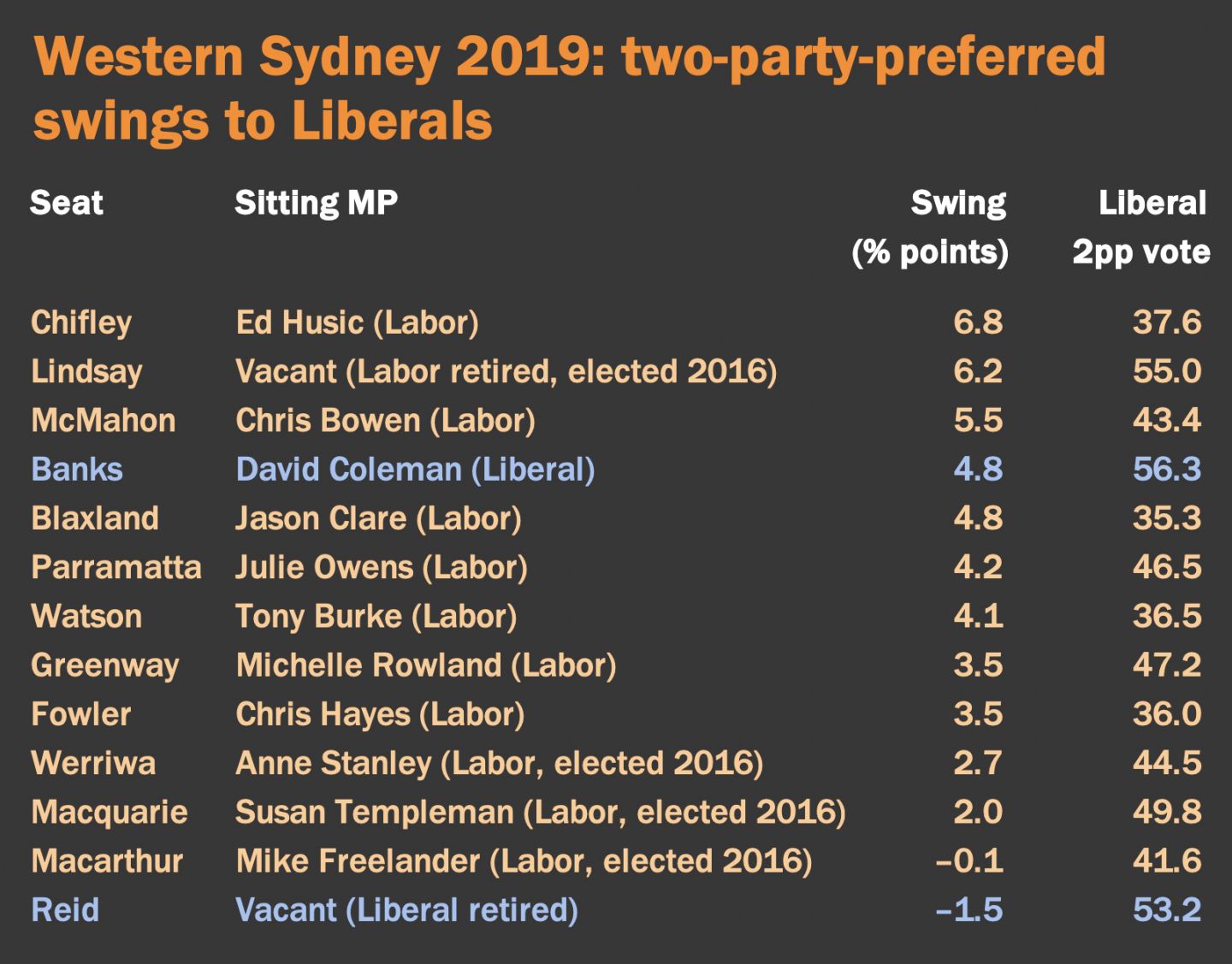

Western Sydney’s performance at the last federal election — when it famously swung to the Morrison government — is a good example. (Much of it was simply reversing outsized swings to Labor in 2016.) This chart shows the swings to the Liberals in decreasing order of size. The two seats at the bottom — one the seat of a retiring Liberal MP, Craig Laundy — swung to the opposition, the rest to the government. The next three were sophomore seats: Labor members elected at the previous election; having been largely unknown candidates in 2016, they had generated at least some profile in the community in the intervening three years.

(Lindsay, which swung big, would have been sophomore if the Labor MP Emma Husar had not been shafted. As it was there was no sitting member on offer.)

As Reid shows, personal vote effects also tend to show up when an MP retires (or is forced out by their party), particularly if they’ve been there for a long time. In 2019 four NSW seats had departing MPs. Lindsay, as mentioned, had no personal vote effects, but the other three, all Coalition-held — Reid, Cowper and Gilmore — swung to Labor, and Gilmore even changed hands. (And not just because of the disendorsed MP; Scott Morrison captain’s call of Warren Mundine as candidate proved a disaster.)

Back in 2016 Julia Banks was the only Liberal candidate to take an electorate from Labor. Buried in the fine print of this achievement was the fact that it was an empty seat, the sitting Labor MP of sixteen years, Anna Burke, having pulled up stumps. Burke had built up a good personal vote, particularly during her term as speaker in the Gillard government, so a drop in the Labor vote was inevitable.

Personal vote effects don’t always show up, but they usually do. All sorts of other things matter too. Sometimes sitting MPs end up with negative personal votes; they are a drag on the vote and the party would have been better off with somebody else there. That was the case in Warringah in 2019, when Tony Abbott’s unpopularity created the opportunity for an insurgent. Labor, the party of unions and workers, could never have won that upper-middle-class seat, but an independent stood a chance in a compulsory preferential system. Step forward Zali Steggall. Independent candidates are hoping to do this country-wide in 2022. Their endeavours will nearly all come to nothing, but one or two, maybe, could get through.

Major party campaigners tend to be sceptical of personal vote effects, particularly sophomore surges. They instead nominate the seats to throw resources at, and if they do relatively well there, they claim vindication of their campaigning prowess. In reality they chose these electorates because conditions were welcoming.

Maybe the most dramatic example of this was in 2010, when the Gillard government suffered a swing that should have put them into opposition, at least according to the pendulum. Of the NSW seats the apparatchiks crowed about “saving” — Eden-Monaro, Page, Robertson, Greenway, Lindsay — all but Robertson was sophomore (and Robertson was complicated.)

In general, the sophomore surge means that governments tend to do well, swing-for-seat, at the election after they’ve taken a big bunch of them off the other side. In October 1998 the Howard government survived a swing that, if uniform, would have sent them into opposition. It was put down to brilliant marginal seat campaigning, particularly in New South Wales, where it turned the then state Liberal director into a rock star, but only until the Carr government’s huge win at the state election in March the next year, which sent the same party official to the electoral dog house.

Retiring MPs in 2022 (announced so far) can be found here. Sophomore seats are here. Over the summer I will write a much bigger, wonkier examination of personal vote effects in 2022.

Have a wonderful break everyone! •