Is the Party Over? is the book’s title, and its subtitle is The Future of the Liberals. A topic for our time, you may think, and you would be right. But it was published in 1994 and written by Chris Puplick, a former Liberal senator and shadow minister.

That was the year after John Hewson lost the unlosable election to Paul Keating. Labor had been in power for a decade, Australia had endured a severe recession in 1991 and the popular Bob Hawke had been replaced by the unpopular Keating. And yet the Liberals lost. Twenty-eight years later, the arguments in Is the Party Over? have striking resonances.

Puplick is what was once called a Liberal “wet,” as opposed to the party’s conservative “dries.” (They’re better known these days as small “l” liberals, or moderates.) Among the reasons he cited for Hewson’s loss to Keating was the pledge to opt out of environmental policy by deferring to states’ rights — or, as Puplick put it, “the right of states to butcher the environment.” The Coalition’s advocacy of nuclear power was “plainly stupid.” It had failed to recognise the rights of Aboriginal Australians. Its narrow-minded, penny-pinching approach to the arts and “bizarre threats to all but destroy the great national institution of the ABC” had cost it votes in the arts community. Its “crass homophobia” had alienated the gay and lesbian community.

He argued that the party also had a problem with women dating back to 1987, when the John Howard–led Coalition opposed the Hawke government’s affirmative action legislation for government employees. “Indeed,” wrote Puplick, “John Howard’s problem in the eyes of many feminists was compounded by the fact that the two most ardently pro-feminist members of his shadow cabinet, Peter Baume and Ian Macphee, were both ruthlessly eliminated from it.” Baume had been shadow minister for women’s affairs. Puplick himself lost his seat in the 1990 election after being relegated to third place on the NSW Senate ticket.

Yet the Liberal Party had a proud track record on these issues, Puplick argued, pointing to measures including creating the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park and the Kakadu and Uluru national parks, steering through the 1967 referendum that led to Aboriginal people being counted in the census, and legislating in the states to remove discrimination on the basis of sexuality.

In 1989, when Puplick was shadow environment minister, the Coalition adopted a target of a 20 per cent reduction in greenhouse gases by 2000 — well ahead of any commitment by Labor. Who could have imagined that a third of a century later, some Liberals and Nationals are still arguing the toss about human-induced climate change and whether we even need targets? Or that the Liberals would revisit the option of nuclear power, which is no more popular now and makes even less sense given the low cost of renewables.

Of course, more important factors were responsible for the 1993 election loss, including Hewson’s complex and ambitious Fightback! package, which included a GST and significant changes to Medicare. As well, Keating’s formidable political demolition skills exposed Hewson’s limitations as a campaigner.

Nevertheless, Puplick’s key point had force: the Liberals couldn’t afford to write off the voters they had alienated. The same choice, on many of the same or similar issues, faces the party after this year’s election loss.

Despite Howard’s argument that the Liberal Party is a broad church, the moderates lost influence in the years he presided over the party. Now the teals have scythed through their already depleted ranks, defeating moderates Trent Zimmerman, Katie Allen, Dave Sharma, Jason Falinski, Tim Wilson and Celia Hammond, as well as taking out Josh Frydenberg.

Scott Morrison’s election strategy assumed he could find an electoral majority in the outer suburbs and regions, despite the Coalition’s negatives on climate change, women and government integrity. Indeed, he was prepared to alienate small “l” liberal voters by advancing the credentials of his handpicked candidate in the seat of Warringah, Katherine Deves, and endorsing her criticisms of transgender rights. That failed both as a political wedge and as a strategy to attract conservative votes.

“It was a strategic, dog whistle–type manoeuvre to awaken culture war anxieties in outer-suburban seats,” said the Blueprint Institute, a think tank espousing classic liberalism, in its scathing post-election briefing. “Morrison was actively sacrificing the teal for the new dark blue.”

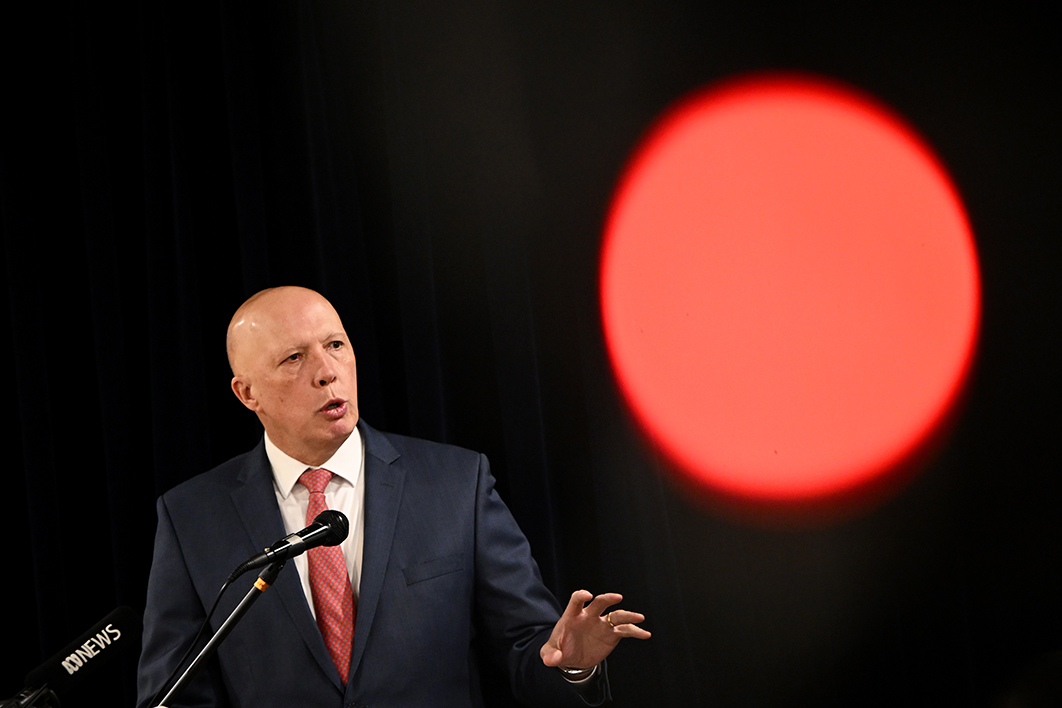

Yet Peter Dutton sees Morrison’s strategy as the way of the future, at least in broad terms. He says that 200,000 voters deserted the Liberal Party for the teals at the election compared with the 700,000 who switched to right-wing parties such as One Nation and the United Australia Party. His office didn’t respond to repeated requests for an explanation of these figures, which appear difficult to reconcile with the election results. “Our policies will be squarely aimed at the forgotten Australians,” Dutton said at his first news conference as leader, “in the suburbs, across regional Australia, the families and small businesses whose lot the Labor Party will have made more difficult.”

As for the teal seats, Dutton thinks that well-off voters can cope with higher petrol prices, whereas “people are putting $20 and $40 in their car because they can’t afford to fill up” in many of the areas he sees the Liberals representing.

One of Dutton’s predecessors, Tony Abbott, has his own instant history of the election result, perhaps tinged with schadenfreude over the losses by Liberal moderates. “This wasn’t actually a climate change election,” he argues. “The question is do we win so-called teal seats back by trying to be even more zealous on climate or by finding other issues on which to appeal?”

Dutton told his party room that the opposition will announce a new target for emissions reduction before the next election. But he didn’t take what many thought was the obvious step — as advocated by Zimmerman and other moderates — of accepting Labor’s target of 43 per cent and moving on. Colleagues say he believes he will be able to link Labor’s climate policies to the rising cost of living.

Senate opposition leader Simon Birmingham, the senior parliamentary moderate, was reduced to tortuously arguing that he would have supported the 43 per cent target if it hadn’t been put into legislation, given that the legislation was unnecessary. Such is the price of party unity.

But Birmingham and other moderates have a very different interpretation of the election result from Dutton’s. Apart from the teal electorates themselves, Birmingham tells me, many other seats were lost to Labor and the Greens because of the party’s loss of “teal-type” voters. “To win those seats back we are going to have to reconcile with those voters and their concerns on issues of inclusion and climate ambition.”

He draws a contrast with the 2019 election, after parliament had resolved the issue of marriage equality “and there were no particular distractions being run in the culture war space. We were able to keep the focus relentlessly on the economy and tax, with Labor’s help, and we won. By 2022, having had internally divisive debates on religious discrimination and then the distraction of transgender issues, they just compounded a sense of intolerance that is out of step with large parts of Australia, particularly in those seats that we lost.”

Fellow moderate, NSW senator Andrew Bragg, emphasises that the Morrison government lost seats to Labor and the teals rather than to right-wing parties. “It is very clear that the fastest way back to government is to reclaim the Liberal heartland,” he tells me.

Bragg has calculated an average Liberal primary vote of 41 per cent in the (broadly defined) inner-city Sydney seats of Warringah, retained by independent Zali Stegall; North Sydney, Wentworth and Mackellar, all won by teals; Reid and Bennelong, won by Labor; and Bradfield and Berowra, held by Liberals despite significant swings against them. To replace these eight seats, he says, would require winning in areas of western Sydney such as Bankstown, Parramatta and Liverpool, where the average Liberal primary vote was around 23 per cent. “It is a pipedream,” he says. “Our primary vote is simply too low.”

By contrast, lifting the Liberal vote by as little as six percentage points to 47 per cent in seats closer to the city should be enough for a win after preferences. “The idea that we abandon heartland seats and not represent people in the inner cities would be the first time the Liberal Party has sought not to represent a large part of the community. It is a politically innumerate approach.” And the story is similar in Melbourne and Brisbane, he says. “All up, it would be giving up on sixteen current or former Liberal seats.”

An analysis by Ross Stitt, a lawyer and political scientist, supports Bragg’s broad point by using the twenty electorates with the highest Yes vote in 2017 for marriage equality as a proxy for socially liberal values. The Liberals held ten of those seats in the 2016 federal election and eight in 2019 but lost all of them to teals, Labor and the Greens this year.

Despite Bragg’s figures, winning back teal seats is likely to be a challenge. Independent MPs in recent periods generally have increased their margins at subsequent elections. Labor has an interest in encouraging its supporters to vote strategically, as it did at this year’s election, to help the teals get re-elected, since it has no prospect of winning those seats itself. Ultimately, events over the next few years, including the performance of the Albanese government, the Dutton opposition and the teals themselves, will determine the future of these seats.

Bragg sees opportunities. “The first thing you need is a philosophy of live and let live,” he says. “Most people aren’t into weirdo culture war issues.” Another requirement is a distinctive economic policy — and this is where he sees openings, given Labor’s “vested interests” through its links with trade unions. He cites the Albanese government’s likely reintroduction of collective bargaining and steps to reduce the transparency of superannuation funds. “So we have to be bold in industrial relations, superannuation and tax. I don’t think we did enough on economic policy in the last election.”

Bragg’s views are echoed by influential Liberals outside parliament. David Cross, chief executive of the Blueprint Institute and a former head of policy and chief-of-staff to NSW Liberal education ministers, makes the point that Tony Abbott seems to have missed: every one of the teals ran campaigns attacking the Coalition’s weak position on climate change. “They pitched themselves as disaffected small ‘l’ liberals,” he says, “and the electorate responded.”

Cross believes that Liberals, “as friends of the free market,” know that liberalism is best placed to enable conservation and climate action. “They know we should be supporting the private sector’s desire to speed up the exit of coal from the grid rather than forcing energy companies to keep open loss-making coal-fired power stations — a perfect example of government overreach if there ever was one.”

Not facing the restraints applying to federal MPs, the Blueprint chief makes another point: there is no alternative. “Even in an alternate reality where Matt Canavan is prime minister, you are going to end up with net zero because you will be dragged there by the global economy. There is no conceivable world where in fifty years from now we won’t be in a net zero economy. That being the case, do we want to get the wooden spoon or take the opportunities?”

The concern of small “l” liberals like Cross is that the party has broken away from its moorings to become reactionary rather than liberal. “Whether you look at the treatment of LGBTQI students at school or the environment or even tax and fiscal reform, which policies in the party’s platform can you point to as being consistent with the philosophy on which the party was founded?” he asks. “You can see why the party has bled votes — to the teals because it is not a liberal party and in some other seats because it is not a conservative party.”

Rather than shifting to the populist right, says Cross, the party “must re-engage with classical liberalism and stop listening to those who bastardise their party’s philosophy to shroud Luddite attitudes towards progress and veil naked bigotry towards people that make them uncomfortable.”

As for the outer-suburban strategy, Cross calls it the “mythical base.” The idea that the party needn’t focus on winning back teal seats is “ludicrously misguided.” These are areas where people have voted for the Liberals all their lives, he points out — until May this year. “As recently as three or four years ago, the Coalition was holding these seats by massive margins. The idea that this [loss of support] has suddenly become a long-term trend, I don’t buy at all. What it does show is that the federal party, particularly under Morrison, has just diverted so far from these voters’ policy priorities. It shows the extent to which they have abandoned liberalism.”

The moderates’ arguments find support in the re-election in May of Tasmanian Liberal Bridget Archer, who defied the national voting trend to secure a small positive swing in the ultra-marginal seat of Bass. Archer stood up to Morrison and crossed the floor in support of an integrity commission and LGBTQI rights, and since the election has voted in favour of Labor’s legislation for the 43 per cent emissions reduction target.

Might the NSW Coalition government be the model for the federal party to follow? True, it has become mired in all sorts of scandals this year. And premier Dominic Perrottet hails from the conservative wing of the party, though the moderates say he shares many of their concerns, particularly over the federal party’s resort to populism.

But when it comes to policies, the government in Macquarie Street arguably does set a positive example. “The policy platform of the NSW government has been really successful,” argues Cross, citing moves on climate change and other issues that make it less likely to be threatened by a teal wave.

One answer to the question in the title of Puplick’s book, Is the Party Over?, came two years after its publication with John Howard’s landslide win against the Keating government — the start of four terms in office. Howard didn’t win by embracing moderate policies; rather, he focused on neutralising negatives, including his party’s hostility towards Medicare and his own fears about Asian immigration. By offering the smallest possible target, he got out of the way of voters who, in the words of Queensland Labor premier Wayne Goss, were waiting on their verandas with baseball bats to deal with the Keating government. Howard exploited the sentiment by aiming, he said, for an Australia that was “comfortable and relaxed.”

When the electoral pendulum swings, it can knock over everything in its path, including perceptions of electoral vulnerabilities. But a vote overwhelmingly against a government does not mean an opposition should forget about adopting policies that appeal to voters.

Despite preaching the gospel of the Liberal Party as a broad church, Howard often acted as though he didn’t mean it. But he was pragmatic enough to sway with the electoral wind. As opposition leader he appointed Puplick shadow environment minister because he saw the traction the issue was gaining with voters. He allowed a conscience vote to overturn health minister Tony Abbott’s ban on the RU486 abortion pill — an issue that had split the Coalition parties. In his last term of government he endorsed an emissions trading scheme to tackle climate change. It was the ideologues in the party, led by Abbott, who took a different path.

Puplick’s basic point remains clear and valid: a party seeking government can’t afford policies that put so many voters offside. As another prominent Liberal put it to me, “Will we win an election on reframing these issues? Perhaps not, but we have to stop losing votes on them.” •