Journalists often lead peripatetic lives, but few have travelled more than foreign correspondent Jill Jolliffe, whose career included covering war in Angola, investigating secret Nazi gold in Portugal and documenting the sex-slave trade in Europe. She wrote for newspapers and news agencies across the world on a wide variety of subjects but will always be associated most strongly with Timor-Leste and its struggle for independence from Indonesia.

Jill witnessed Indonesia’s military incursions first-hand when she was part of a student delegation visiting the new nation in 1975 to celebrate its release from Portuguese colonial rule. A group of journalists covering the invasion for the Seven and Nine networks asked her about conditions at Balibo, a town on the border with Indonesian West Timor that she had just visited.

It was a bush warfare situation out there, she told them, but if they kept their heads down they should be okay. Regardless of their precautions, though, all five journalists in the group were murdered by members of the Indonesian military and became known as the Balibo Five. Journalist Roger East, who was sent to investigate their deaths, was also executed.

Jill — who died in Melbourne on 2 December aged seventy-seven — began doggedly and dangerously seeking the truth about the murders and reporting on conditions more broadly in Timor-Leste. She spent twenty years in Portugal working with the Timorese resistance-in-exile and making secret visits to the island (from which she was banned by the Indonesian government). On one occasion she was captured and briefly imprisoned. Her determination to keep the story alive often met with media indifference and Australian government attempts to play down a complex geopolitical situation.

Her first book, East Timor: Nationalism and Colonialism, was published in 1978, three years after Indonesia’s invasion, and her 2001 study, Cover-Up, became the basis of the highly regarded feature film Balibo in 2009.

Timor-Leste regained its independence after much bloodshed in 2002. By then, Jill had set up the Living Memory Project, which recorded the testimonies of former political prisoners and victims of torture. Her reporting also played a crucial part at the 2007 NSW coroner’s enquiry into one of the murders, which finally established the role of the Indonesian military in all the journalists’ deaths.

“I was told recently that my coverage of the Balibo story was what really alerted people to the East Timor issue and that began it all,” Jill said in a documentary we made together for ABC Radio National in 2017. “I felt proud of that… An injustice is an injustice and it doesn’t change with time and people need to be brought to account.”

After moving back to Australia in 1999, Jill lived in Darwin and then Melbourne, where she wrote Finding Santana (2010) about her secret return to Timor-Leste for a rendezvous with guerilla leader Nino Konis Santana. But her last book, published in 2014, was quite different.

Run for Your Life covered her unhappy childhood with outwardly respectable but violent adoptive parents in the Victorian seaside town of Barwon Heads, and her political awakening at Monash University. Her well-honed sense of rebellion made her a natural for membership of the radical Monash University Labor Club, and her achievements included disrupting a Billy Graham evangelical gathering and being one of the only female speakers at Melbourne’s 1970 anti–Vietnam war march. She also ran a feminist bookshop — Alice’s Restaurant — in Greville Street, Prahran, and helped found an early feminist magazine, Vashti’s Voice.

Jill found out later that her adoptive mother had dobbed her in to ASIO for subversive activities. When she gained access to her file she was amazed and amused by its size.

It was only when she reached her sixties that Jill decided to risk finding out about her birth parents, and that story too is covered in Run for Your Life. To her relief (and with a great degree of trepidation) she discovered that her mother was still alive and willing to meet. “I’ve thought about you every day” were the first words she said to Jill when they spoke by phone.

Having known Jill since her return from Portugal I was honoured to be asked to drive her to the rendezvous with her mother at an anonymous bus stop in a northern suburb in 2013. The woman we saw walking briskly towards us was remarkably like Jill, with her short crop and outfit of baggy trousers, loose shirt and small beaded necklace. Given the age gap was only fifteen years, she could have been Jill’s older sister.

The hug they shared was their first bodily contact in sixty-eight years. They quickly established how much they had in common: both were atheists, passionate about history and politics, and fiercely independent. As Jill said at the time, “I think we shared more than a few genes.”

Although her mother died two years later, the reunion was profoundly healing for both of them.

Jill was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s at the end of 2016. It was a particularly cruel diagnosis for a woman whose life had been spent travelling and uncovering truths in very dark corners of the world, and she took it badly.

In the radio documentary about her life, we covered her medical diagnosis and its ramifications, which included severely curtailed freedoms.

As she commented rather bitterly, “People say that my capacity to cope with [dementia] is very limited but I don’t see it that way, because I have spent most of my life as a foreign correspondent and I’ve been under fire from the Indonesian army and from the American air force and I’ve come up against quite hair-raising situations; I’ve survived all of these, some people might say through my rat cunning.”

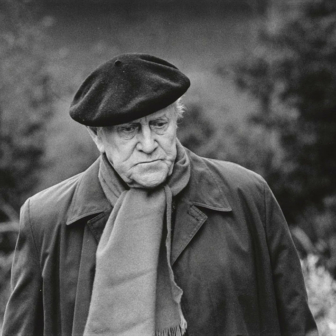

Jolliffe was nuggetty, cynical, sometimes ornery but also generous, witty and fiercely principled. She was also a very fine journalist and, for the people of Timor-Leste, a hero.

One of many fine tributes to her came from Timorese leader Xanana Gusmão: “Jill was an activist, a rebel and a fighter. At great cost to herself, she persistently exposed the reality of the Indonesian military occupation of Timor-Leste and supported the struggle of our people. She is one of us.” •