The greatest and most influential Australian cartoonist of the postwar era, Bruce Petty, died just before Easter this year. Fifty-six years ago, also just before Easter, he was working on an incendiary image:

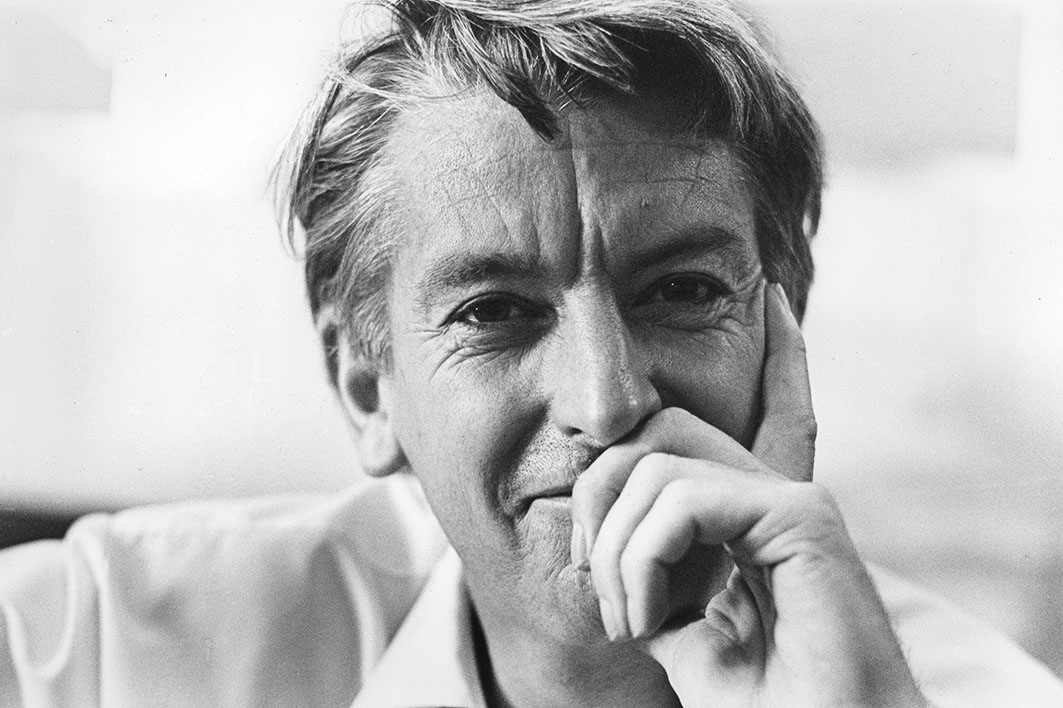

Petty in the Australian, 25 March 1967. Flinders University Museum of Art

In a cross made of newsprint, the words on the upright are Ho Chi Minh’s and those on the crosspiece are Lyndon Johnson’s. You can imagine the indigestion at the breakfast tables of a still very white Australia when politicians’ words burdened a shockingly Vietnamese Christ on a modern via dolorosa. It isn’t pretty or funny, but it is morally and intellectually arresting. It has historical and symbolic depth as well as contemporary bite.

If you’re looking for ground zero of the idea that cartoonists are “of the left” in Australia, Petty’s stint at the Australian during its first decade is it. He sided with the little guy, then asked how the system worked to keep him little and the usual suspects (captains of industry, financiers, the military industrial complex) big. His cartoons can be busy because he thinks in systems and mechanisms and wants to make them operate more fairly and generously.

Petty was always inclined to treat politicians more as lackeys of vested interests and playthings of historical processes than as proper villains in their own right. This, I think, made him deeper than most other cartoonists or, indeed, most other satirists. I put no statute of limitations on this view. Juvenal looks like a grumpy whinger with a brilliant turn of phrase by comparison. Bill Leak could play the man superbly in his caricatures and punchlines, but the shafts of lightning didn’t shed consistent light on Australia as it is, and as it could be.

Petty’s cartoons did just that. The critique changed with the times, as the times demanded, but the golden thread of wanting a better, fairer, more intelligent and independent nation never disappeared into the fabric of daily affairs. On my first visit to interview him in the late nineties, he pointed me to a cupboard where there were “a few pictures of mine.” It was less than a dozen — Petty visited the past often to learn lessons, but never to dwell there. He lived for tomorrow’s paper, and the current art project.

He came a long way from a fruit farm in Doncaster as a child of the Depression, but he never lost the practical attitude to problems and sense of guiding purpose. Every cartoon asks something like “How do you fix this bloody thing, and get it to do what we want?” More or less sequentially, his satire had four great themes.

I have already illustrated the first — the horror and stupidity of war, particularly the Vietnam war. He had been to London and witnessed the collapse of Empire made explicit in decolonisation and the Suez Crisis of 1956. He returned to Australia via Southeast Asia in time to be cartooning during the death of Kennedy, the resignation of Menzies and, most importantly, the incremental decision to join the United States in Vietnam.

Rupert Murdoch’s adventure in national influence, the Australian, was in its initial (wildly) progressive phase, and Petty was its standard-bearer. He was half a generation older than baby boomers threatened with conscription and increasingly inclined to flood the street with moratoria. He also blew up the pomposity of Anzac Day in 1969 with a dismembered soldier’s corpse from the actual war diverting a pious procession of “lest we forget.”

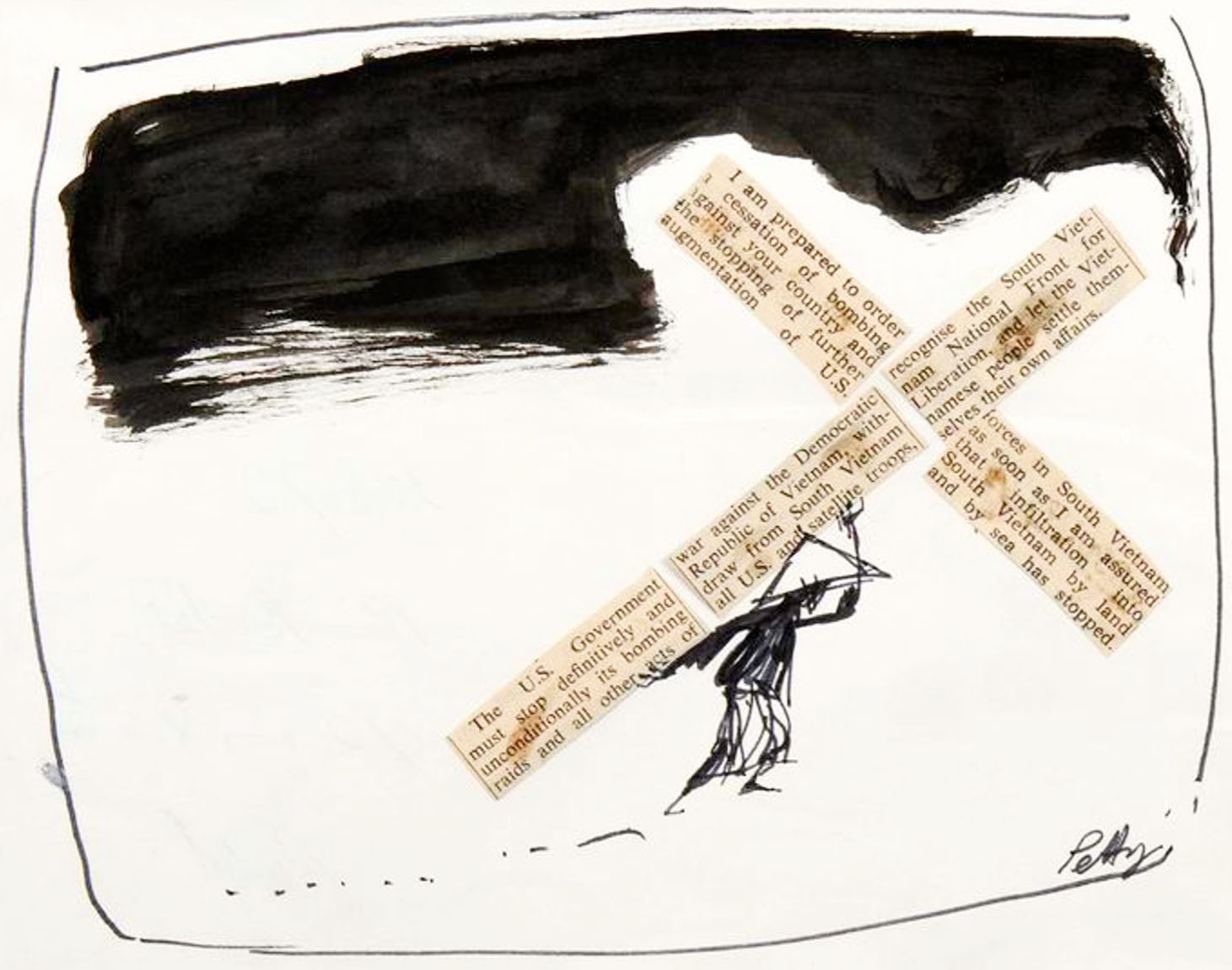

Meanwhile, the Coalition governments were deteriorating comically, and Petty especially “owned” the image of Billy McMahon as a hapless, vainglorious fool with very big ears:

Broadsheet, November 1972. National Gallery of Victoria

It’s funny, in a bitter kind of way, how often people have had recourse to the “worst PM since McMahon” trope in recent years. I wonder if Morrison has reset the clock on that one.

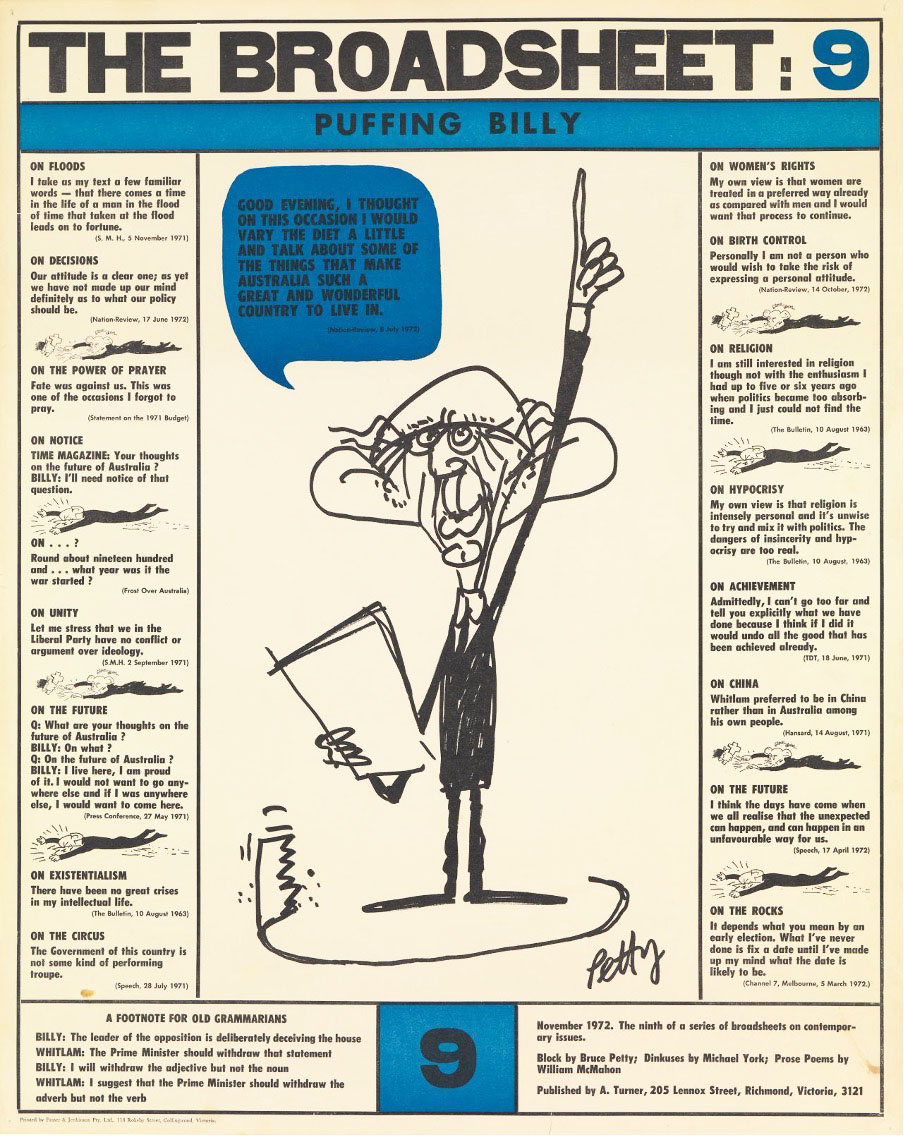

In a series of cartoon books as well as at the Australian, he sought to shape the rebirth of interest in national character and destiny in the dawning post-British age. In the heroic age of this project, the hero — and the exemplar of Petty’s second theme — was Gough Whitlam:

The Australian, 14 November 1972.

The fulfilment of the dream of an open, egalitarian and cosmopolitan Australia under Whitlam was messy and exciting — Petty even donated a logo to the 1974 election campaign. The big hump in his career was when the dream collided with the first of several stages of reaction to the dismissal at the end of 1975. Malcolm Fraser wrongly assumed that normal postwar boom conditions would return with sensible chaps back in the big white cars, a trick Tony Abbott and Scott Morrison tried in recent years with even less success.

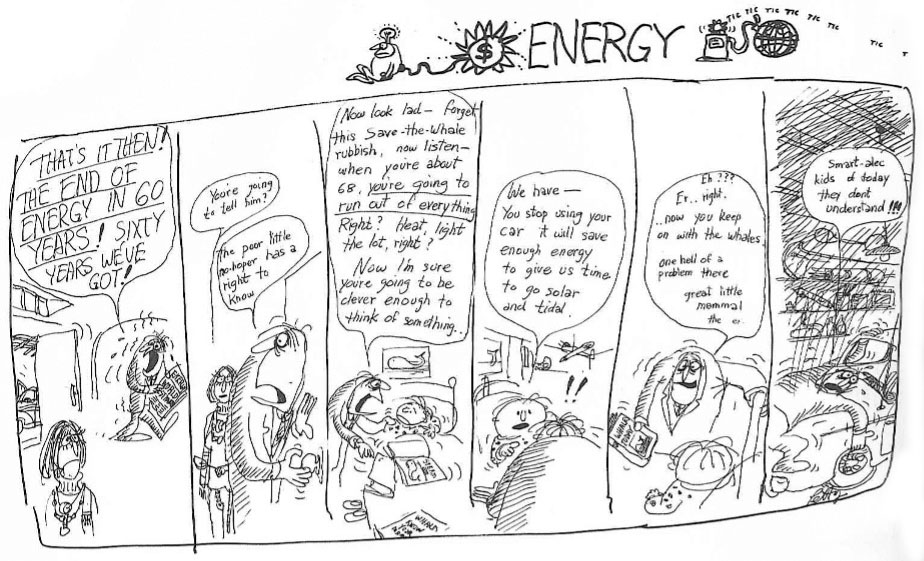

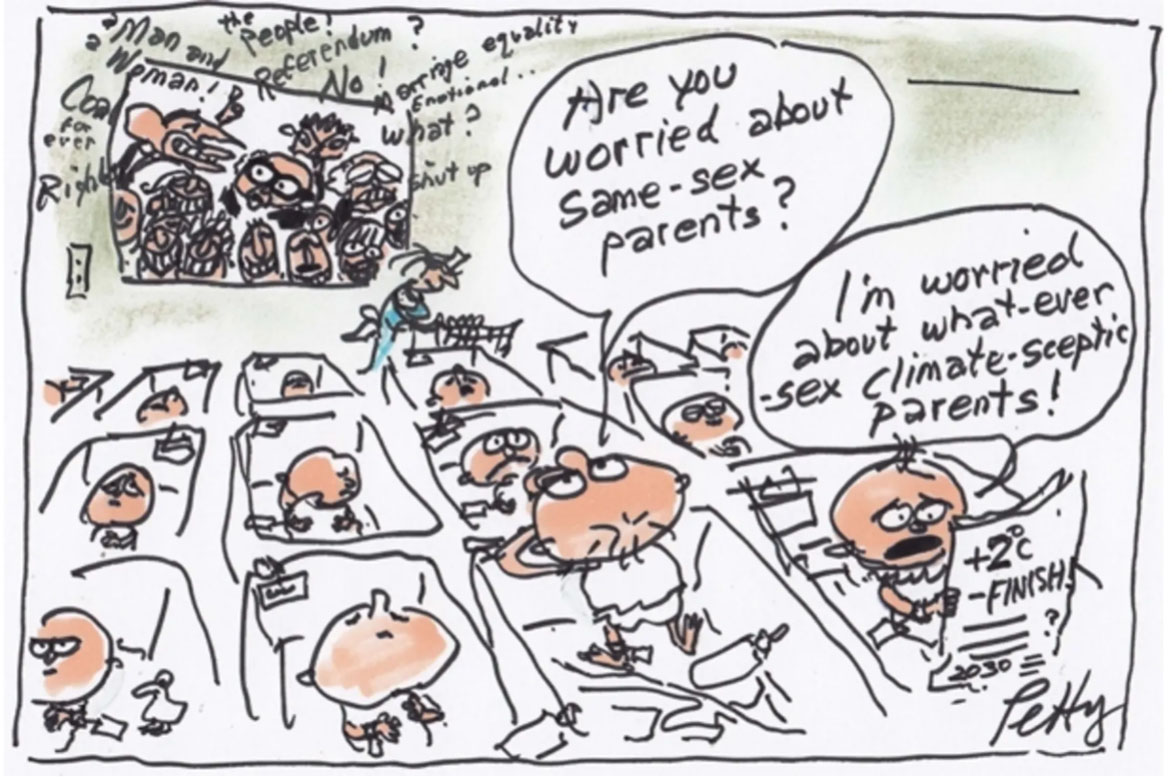

Petty spent the second half of his life exploring his third and fourth themes, a long, intelligent dissent from this “Lucky Country” mentality and from the Reaganite confidence in market forces that came in its train. He never tired of showing how and why the economy should serve human needs and desires rather than its own geometry of indices. And he was farmer’s son enough to recognise that you have to protect long-term interests from human rapacity. Two cartoons, from 1977 and 2015 respectively, show that you can be right a long time as a satirist and not necessarily be attended to:

The Age, 30 April 1977.

The Age, 17 August 2015.

When the Age suggested that he stop cartooning in 2016, at the ridiculously premature age of eighty-six, he was annoyed and disappointed. He lived for the work, and kept drawing anyway, right up to the last months. He understood ideas and the weight of the past, but it was the next paper, the next crop, the next generation that always mattered most. His optimism was informed by clear-eyed experience but was also incredibly robust.

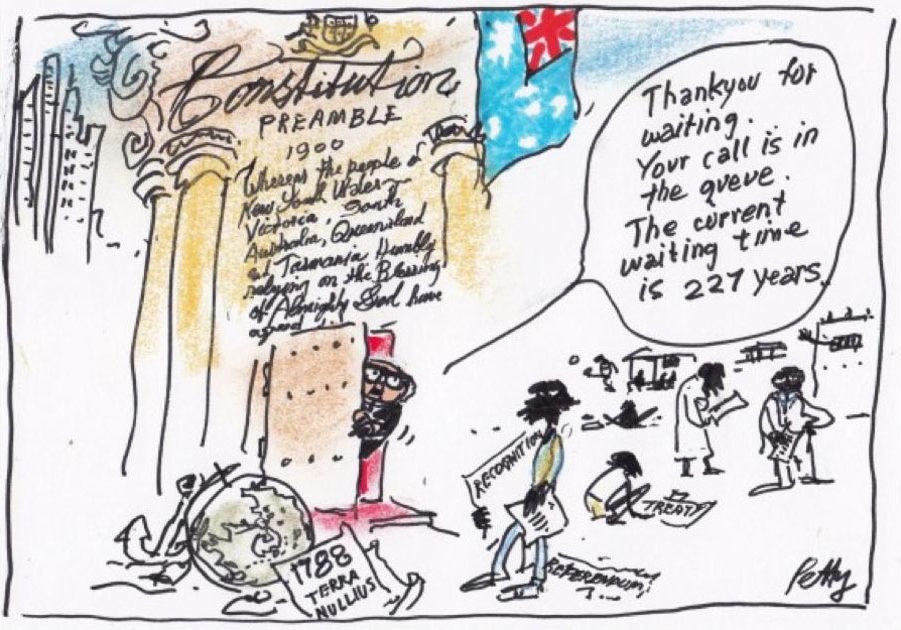

What would he say to the nation today? With his genius for being stern yet quizzical, I don’t think he’d mind having this cartoon thrown back into the current debate over what it is to be a proper nation, one true to its past, present and future:

The Age, 20 April 2015.

Though he is gone now, it wouldn’t be a bad idea for us to look again into the satirical mirror he held up to us for so many decades. We might see something we could fix. •