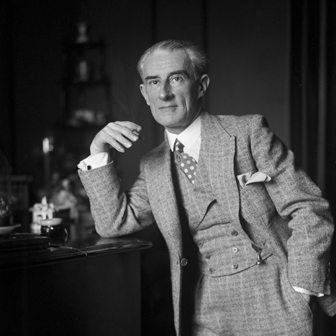

“The best ideas come as jokes. Make your thinking as funny as possible.”

— David Ogilvy

It is difficult to pinpoint the beginning of the Beatles. We might date it to when Paul McCartney joined John Lennon’s group, the Quarry Men, in the summer of 1957, or to when George Harrison joined, the next year. Maybe it was the moment that Stuart Sutcliffe and Lennon came up with a new group name, or maybe the Beatles truly began when Ringo Starr replaced Pete Best in 1962.

Here’s what I think: the Beatles began, in spirit, in 1960, during their first stint in Hamburg (when the group comprised Lennon, McCartney, Harrison, Sutcliffe and Pete Best). Going to Hamburg was immensely formative and not just because they played for so many hours and got better at performing. It was culturally formative. They were far from home, away from the expectations and judgements of everyone who knew them. Relatively few people in this strange and thrilling place spoke or understood English. So the Beatles formed their own private society with its own micro-culture, composed of clowning, teasing, dreaming, wordplay and music (a culture which germinated in all the time John and Paul had spent eyeball to eyeball over guitars in each other’s homes in Liverpool). That micro-culture was the Beatles. Within four years, it had eaten the world.

In fact, we can be more precise. The night that the Beatles really became the Beatles was the night that they began to “mach schau.”

They had been playing at the Indra, a small and grotty club in the red light district, run by Bruno Koschmider, who had recruited them from Liverpool. Koschmider wasn’t happy with how things were going. The job of the Beatles, from his perspective, was to sell beer. That meant luring customers in off the street by making a loud noise, and then keeping them there by putting on an entertaining show.

But the Beatles were refusing to put on a show. They hated anything that smacked of showbiz, like dance routines, and they disdained stagecraft. They saw themselves as beatniks; they were cool. And that meant they were boring. They just stood there and played songs, as customers tumbled in and wandered out again. Koschmider complained. He wrote to their manager back home, who wrote them a strongly worded letter, which they ignored.

Then one night, Koschmider’s day-to-day manager, Willi Limpensel, started yelling at them: “MACH SCHAU! [Make show!] MACH SCHAU!” The Beatles found this alarming and hilarious. Lennon was first to respond. Taking Limpensel’s instruction as a goad, he started diving around the stage as they played, lurching toward the mic, duck-walking like Chuck Berry. He sang lying on the floor, and pretended he had a bad leg. Paul and George picked up on John’s wild parody of stagecraft and started fooling around too.

Finally, the Beatles were putting on a show. But rather than by attempting to emulate the bland professionalism of rival acts, they were doing it their own way. “We did ‘mach schauing’ all the time from then on,” said John. Within weeks, the Indra was full of dancing, beer-drinking customers every night. The Beatles were no longer just another British beat act, but a unique experience: uninhibited, funny, forceful. They had learnt how to share their internal culture with an audience. Koschmider moved them to a bigger club.

Six years previously, at the close of a long, tiring and fruitless recording session in Sun Studio, Memphis, the nineteen-year-old Elvis Presley began to goof around. Sam Phillips, the studio’s owner, had put this talented, shy kid together with a guitarist and a double bass player in the hope they’d come up with something worth releasing. But the session hadn’t caught fire. In a break between takes, the group started loosely playing a blues song called That’s All Right Mama, by the Black singer Arthur Crudup.

The guitarist Scotty Moore recalled, “All of a sudden Elvis started singing this song, jumping around and acting the fool.” Presley sang this blues song in a country and western style. He sang it fast and put a funny little hiccup in his voice. His backing group, bemused at first, played along. Sun’s boss, Sam Phillips, who was in the control room, put his head round the door to ask what they were doing. “We don’t know,” they said. “I like it,” said Phillips. And so rock and roll, as the world (including Lennon and McCartney) came to know it, was born.

In 1992, a group called Radiohead were in a studio in Oxfordshire, attempting to crack their debut single. The sessions weren’t going very well. None of their songs hit home, and their producers weren’t impressed. While rehearsing the group played a song the group’s lead singer, Thom Yorke, had written years before, just to loosen up. It was called Creep. The producers loved it, but Yorke informed them that the melody and chords had been lifted from The Air That I Breathe by the Hollies.

When the sessions continued to fail, the group was reluctantly persuaded to record Creep, just to see how it sounded. The group’s lead guitarist, Jonny Greenwood, thought the song was so lame that he decided to fuck it up by hitting some ridiculously grandiose thunderbolts on electric guitar during the verse, and power chords during the chorus. Greenwood, who thought he was killing off the song with a joke, had unlocked its hidden majesty. As Yorke observed later, that guitar is the sound of the song slashing its wrists: “Halfway through the song it suddenly starts killing itself off, which is the whole point of the song really. It’s a real self-destruct song.”

Creep became a huge global hit, launching Radiohead into orbit (a share of the royalties went to the songwriters of The Air That I Breathe). It contains some of the fundamentals of the group’s subsequent sound, absent until then: a sense of drama and dynamic contrast, shifting from soft and intimate to loud and bombastic. It also defined Thom Yorke’s artistic personality: self-loathing yet proud, sardonic yet painfully sincere.

Why is that great leaps forward often start off as jokes? I recently wrote about how important it can be to turn off your inner critic, and this is particularly true for anyone engaged in a creative endeavour. Anything that doesn’t exist except in your own mind is prone to seeming ridiculous when it’s aired. Since most of us hate seeming ridiculous, our mind finds multiple ways to cut off weird ideas at the pass.

One of the ways we can smuggle them past the internal censor is in the form of a joke. You don’t have to be a full-on Freudian to see the truth in Freud’s proposal that jokes are the release of pent-up subconscious energies. Our jokes allow us try out new thoughts and behaviours, while insuring ourselves against the cost of failure or embarrassment. If it doesn’t work out — well, we were just having a laugh.

I’m not saying that Elvis knew he wanted blend blues and country and then spotted an opportunity to do it. I’m saying that by moving into joke mode — by goofing around — he switched off his inhibitions and expanded his sense of the possible. He didn’t do this strategically; he did it because he was tired and little desperate, like Radiohead were after so many hours of failed takes, or the Beatles were when on the verge of being fired and sent home. In all three cases, entering into joke mode allowed these musicians to unlock some kind of truth or sensibility hitherto inaccessible.

Humour was crucial the culture of the Beatles, more so than almost any other band, and I don’t think this is unrelated to their matchless record of musical innovation. That other titan from the sixties, Bob Dylan, is often discussed as if he’s deeply serious, but of course he is very funny. His early albums include brilliant comic riffs like Talkin’ World War III Blues and Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream and many of his “serious” songs have jokes in them (“I can’t help it if I’m lucky”). In fact I’d bet that some of his best known “serious” songs started off as jokes. (The closing lines of Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right are funny and heartfelt at the same time.)

It would be dull to conclude that we should “take jokes seriously.” But I do think we should listen to jokes for the potential that can be secreted inside them, just as Sam Phillips listened to Elvis messing around and heard the future of popular music. That includes your own jokes. When you joke about your hopes and dreams you’re sometimes describing what you haven’t yet admitted is your most heartfelt wish. Sometimes you’re essaying a genuinely good idea.

There’s a dark side to this process too, of course. We can all think of public figures who have used humour while pursuing harmful or nefarious ends, and sometimes, bad things start off as jokes. I’ll leave you to decide into which category the following example falls. From Walter Isaacson’s authorised biography of Elon Musk:

On the Friday after the Twitter board accepted his offer, Elon Musk flew to Los Angeles to have dinner with his four older boys at the rooftop restaurant of the Soho Club in West Hollywood. They did not use Twitter very much and were puzzled — why was he buying it? From their questioning, it was clear that they didn’t think it was a great idea.

“I think it’s important to have a digital public square that’s inclusive and trusted,” he replied. Then, after a pause, he asked, “How else are we going to get Trump elected in 2024?” It was a joke. But with Musk, it was sometimes hard to tell, even for his kids. Maybe even for himself. •

This article first appeared in Ian Leslie’s Substack newsletter The Ruffian.