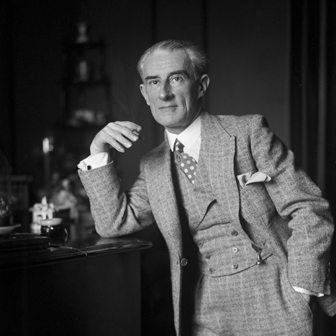

There’s a story about Hubert Parry, King Charles’s favourite composer, hearing Arnold Schoenberg’s atonal Five Orchestral Pieces Op. 16. It was in 1914, two years before Parry composed “Jerusalem” to William Blake’s words.

The concert was at London’s Queen’s Hall and Schoenberg himself was conducting the New Queen’s Hall Orchestra. At the end of the performance, a young Adrian Boult felt a thump on his shoulder and there was the elderly Parry.

“Bless my soul that’s funny stuff,” he said. “I must say I rather like it when they do it loud like Strauss, but when it’s quiet all the time like this, it seems a bit obscene, doesn’t it?”

There are still those who think Schoenberg’s music is “funny stuff” and possibly even some who consider it “obscene,” but London has been hearing it now for well over a century. The world premiere of the Five Orchestral Pieces had taken place there eighteen months earlier in September 1912 at a Promenade concert by the same orchestra conducted by Henry Wood.

Mr Robert Newman’s Promenade Concerts, as they were originally known, began in 1895. Newman, manager of the Queen’s Hall, wanted to expand public taste for music and, in Wood, found the ideal musician, a missionary on behalf of unfamiliar repertoire and a moderniser in terms of orchestral standards; in his quest for exact intonation, Wood was known to go around his orchestra with a tuning fork prior to concerts.

Over its 130 years, the two-month-long summer concert season — called the Henry Wood Promenade Concerts following Wood’s death and, today, the BBC Proms — has greatly evolved. After the bombing of the Queen’s Hall during the Blitz, the concerts moved to the Royal Albert Hall and, in time, out to other venues — even, recently, other cities. The range of artists has continually broadened, as has the repertoire, expanding to include complete operas, music from the Renaissance and Middle Ages, music from India, Thailand and Japan, jazz and hip hop.

But one thing has remained constant. New works — Wood called them “novelties” — have been a feature of these seasons from the very start, their presence more traditional even than Parry’s “Jerusalem,” which Wood only introduced in 1942 (it was another decade before it turned up on the Last Night). In many cases, thanks to the Proms, new works quickly ceased to be novelties. Ethel Smyth’s overture to her opera The Wreckers was played in every Proms season from 1913 to 1933, by which time it must have been extremely familiar to regular attendees.

The BBC’s involvement in the Proms began in 1927 and it was a natural fit, John Reith’s philosophy of public broadcasting matching Newman and Wood’s approach to their concerts. Adrian Boult, founding conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra, shared that philosophy and had a similar attitude to Wood when it came to including “novelties” alongside familiar works. In his final Proms season in 1977, the eighty-eight-year-old Sir Adrian conducted Malcolm Williamson’s Organ Symphony, with the composer himself at the organ.

William Glock’s tenure as the BBC’s controller of music and, therefore, the Proms (from 1959 to 1973) is often considered to be the moment modernism arrived in the Albert Hall, but it was already there. Glock’s main innovation was to bring in music from the fourteenth, fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, which had hitherto been largely ignored by programmers. But he also brought Pierre Boulez, first as composer/conductor, later as the BBC Symphony Orchestra’s chief conductor (1971–75), and this year’s Proms, which began on 18 July, celebrate the Frenchman’s centenary.

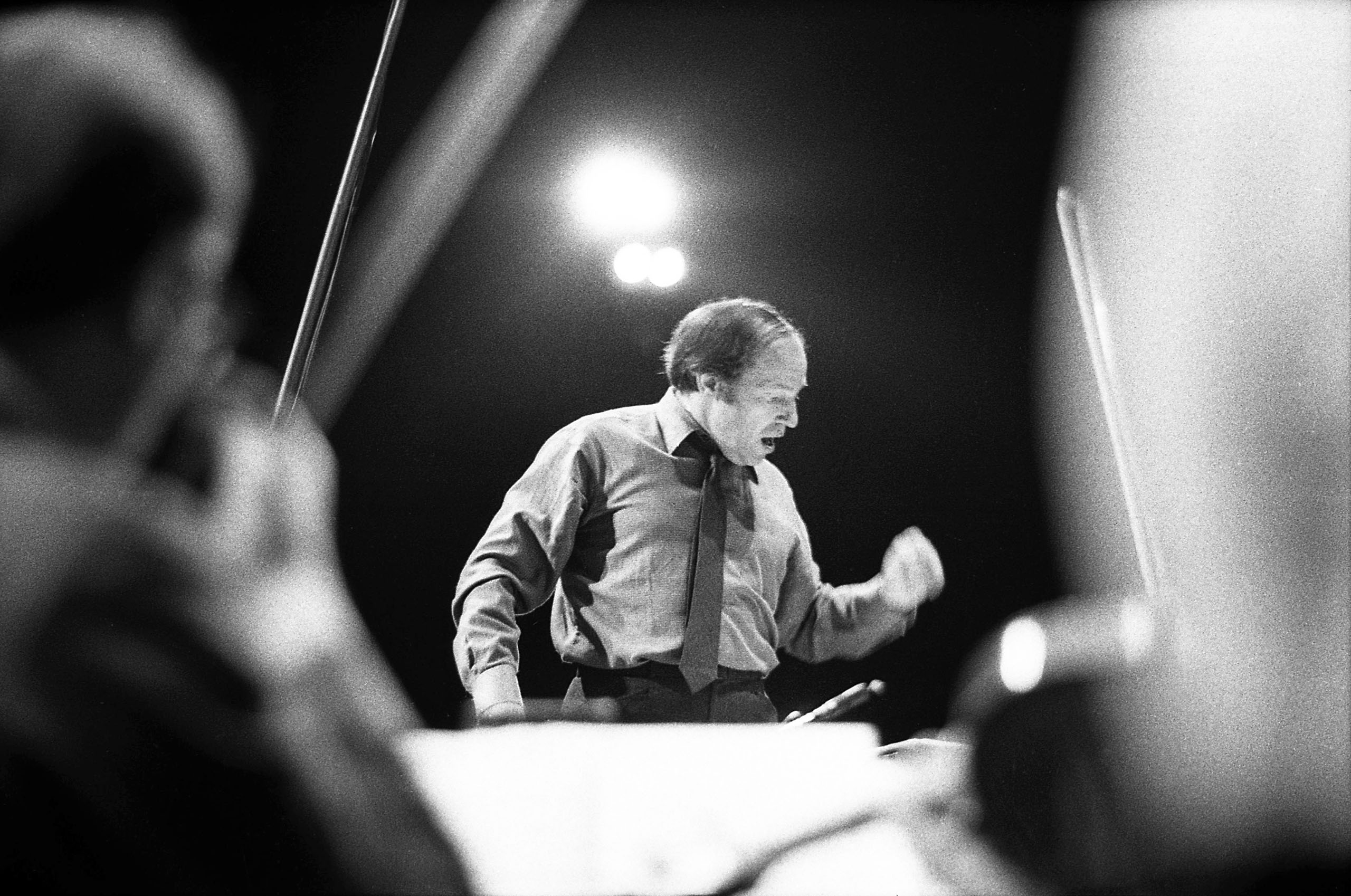

We still hear the cliche that Boulez was a “high priest” of modernism. Like most cliches it contains an element of truth, but is ultimately unhelpful. It certainly doesn’t explain how Boulez became a Proms hero. In that regard, his skills as a conductor and communicator were more germane. No less an authority than Otto Klemperer considered Boulez the finest conductor of his generation, and, as a proselytiser, Boulez was in his element at the Proms. Not that he spoke from the podium, but his programming — full of surprising and provocative juxtapositions — spoke for him. His concerts made you think.

In this, he fitted the model established by Wood and continued by Boult. Wood would certainly have approved of Boulez’s famously exact ear for tuning and balance, and while Boulez the conductor used no stick, in contrast to Boult’s baton of half a metre, the two men’s cool, clear beat was remarkably similar. They shared a single concert, the opening night of the 1974 season, at which Boulez conducted a Haydn Mass and Boult Schubert’s last symphony.

Boulez conducted sixty-nine Proms between 1965 and 2008 and became an audience favourite. His concerts were full of Wood’s “novelties” — recent works and older pieces, long neglected. Yet perhaps most memorable was how those programs were assembled, often mixing chamber music with works for large orchestra. Schoenberg’s Pierrot lunaire for reciter and five players appeared one year alongside Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, another year with Mahler’s fifth. When Glock retired, Boulez prefaced a performance of Mahler’s mighty Resurrection symphony with Mozart’s E-flat piano quartet played by Glock himself and members of the Lindsay quartet.

Boulez championed twentieth-century modernists from Debussy to Berg, Varèse to Stockhausen, and certain nineteenth-century composers — Schumann, Berlioz and Wagner were favourites. At the same time, the Proms represented an opportunity for him to explore music that was novel to him. On the opening night of the 1973 season, for instance, he conducted Brahms’s German Requiem, a work well outside his normal repertoire. You can find the performance on YouTube and while no one would call it “idiomatic,” Boulez’s ear for tuning and balance scotches the popular belief that Brahms’s orchestration was muddy. In this performance, the music glows.

In his final Prom, Boulez ended as he had begun. Aged eighty-three, he presented a concert devoted to music by Leoš Janáček, a composer he had come to late and whose works he had never before conducted at the Proms. •