When Jamie Hanson reviewed the documentary Turn Every Page for Inside Story, he singled out a scene — a search for a yellow pencil — that stayed with me too.

The writer Robert Caro and his editor of fifty years, the late Robert Gottlieb, have met at the Manhattan offices of Alfred A. Knopf to work on the still-incomplete fifth volume of Caro’s “three-volume biography” of Lyndon Johnson. Finding the pencil they need is proving tricky for these two elderly men. People search through drawers and come up with pens and sharpies, which the men reject. Someone finds a mechanical pencil but that, too, isn’t right. Caro and Gottlieb want one of those yellow pencils, because, it is implied, it’s what they always have. It’s important to use the correct tools of the trade.

Turn Every Page is a wonderful piece of filmmaking by Gottlieb’s daughter, Lizzie. I have watched it four times now, partly for the relationship between the two men, which, at one level, is the relationship between any writer and editor but in this case, after half a century, runs deep; partly because, when the United States is going to the dogs, it is reassuring to watch civilised Americans arguing over semicolons. In my line of work such details are also important. And I feel considerable empathy for everyone involved in that pencil search.

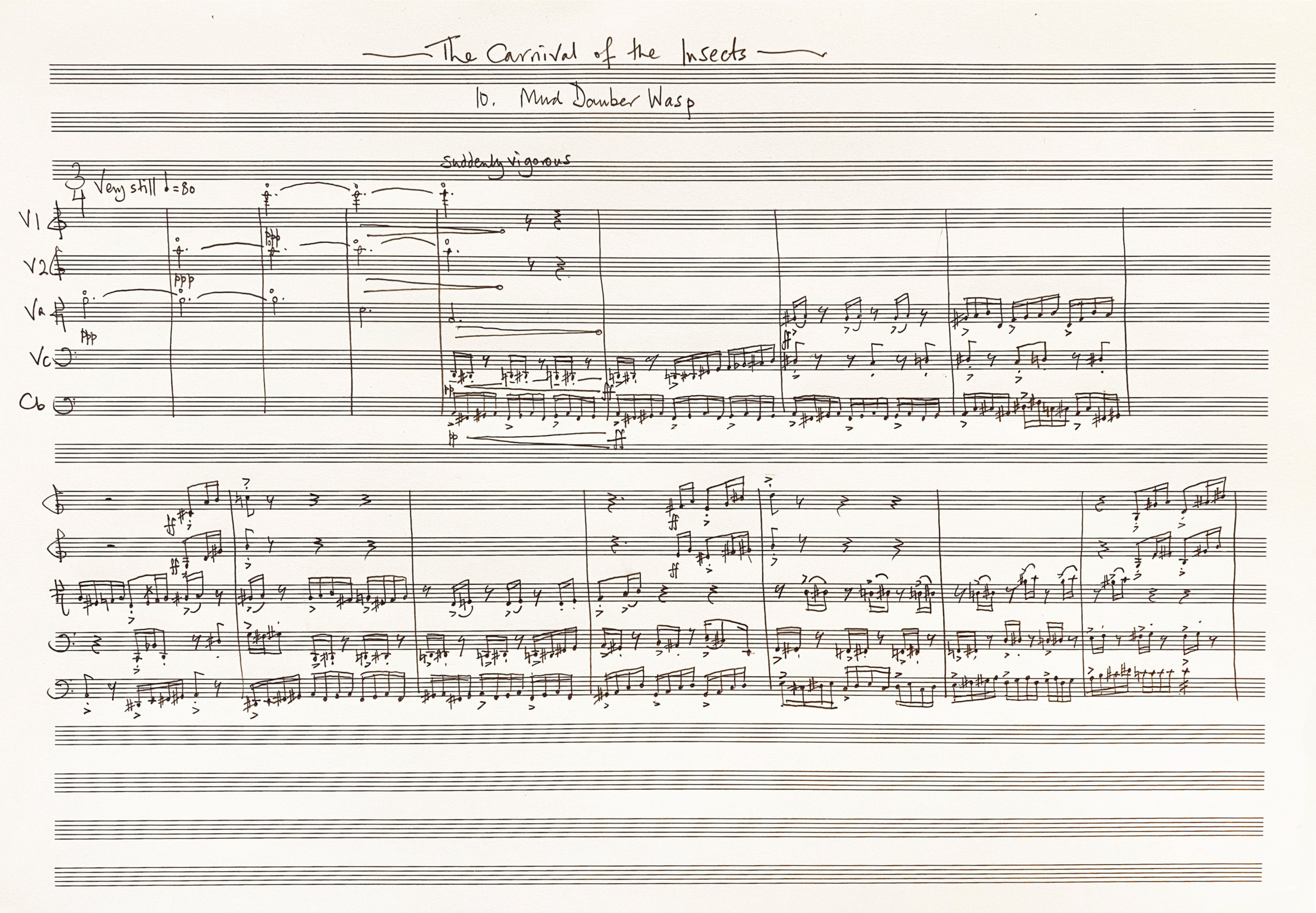

Most of my composer colleagues now work on screens, clicking pitches and note values, dynamics and articulation markings, copying and cutting, pasting and deleting. I am not the last composer to write music on paper with a pencil, but I am possibly among the last. For me, composing is a form of manual labour. I like to feel the pencil on the page. I like to press, but not too hard, because then when I rub out (which is often) the indentations remain. There is something about the making of marks that is directly related to the sound of the music in my head. I write loud and quiet notes differently — the physical sensation is different.

The pencil itself must be 2B. My artist neighbour, Ben Quilty, says it’s “the king of pencils,” and I do feel that, in some senses, I am making a visual work of art. I like to work on large sheets of paper, so I can map out the piece, and so my eyes can take in as much music as possible at a glance (if the music is fast, this might be just a few seconds). Just as with a visual artist, the quality of the paper is important. There’s a practical aspect to this — rubbing out on cheap paper leads to holes — but there’s also something psychological, for if I’m using good quality paper then the music itself had better be worth it.

I am not a performer, but I’ve recently come to realise that, for me, composing is a kind of performance — perhaps, more accurately, a kind of practice, since there is no one present to witness it. Even if there were an audience, there would be nothing for them to hear: some humming and whistling, perhaps, the occasion fumbling through a passage at the piano. But in the physical act of composing with a pencil, I am making musical movements, pressing harder, pressing more lightly, gliding the pencil slowly across the page, then quickly, sometimes getting into a rhythm.

Decades ago, I also used to copy up the completed music in ink on thick transparent paper. When I made a mistake, I would allow the ink to dry then lightly scratch the offending error off the paper with a razor blade. I loved the business of hand-copying and was good at it, the aim always to make the music look as impressive as I hoped it would sound, the score attractive enough that a player would want to spend time with it. The trouble was it took up too much of my time.

So now I pay others to typeset my music using the software most composers employ in order to compose. I have occasionally been tempted to use the software myself, because composing on screen would mean that when the piece is finished the score is ready to print. The saving of time and money would be significant. But I find it impossible to imagine starting a piece on a computer. I need a big, blank piece of manuscript paper, at least A3, and the heavier the better.

Recently, I have to report, the quality of my favourite manuscript paper has diminished. A new consignment turned up and while, superficially, it looked the same, as soon as I began turning the pages I realised it was a lighter than I was used to. My disappointment has not yet subsided. It’s the same with the pencils. Some years ago, I made the transition from proper pencils to mechanical ones because they stayed sharp. But it seems you can no longer buy mechanical pencils filled with 2B leads. You have to buy the leads separately then empty out the HB leads from the pencil and replace them. More disappointment.

Most of the world’s music isn’t notated or, if it is, employs some form of tablature as an aide-mémoire. But in Western art music the score has long been the means by which the music is thought up and its details worked out. It is also how this information is precisely communicated to the players. If I am composing music for players who are using their bodies to play acoustic instruments, creating sounds that depend on the pressure and speed of a bow, the heaviness of a pluck or the length of a breath, it seems to me appropriate that the music itself is imagined, developed and written down by hand. •

Andrew Ford’s The Carnival of the Insects (with accompanying poems by John Kinsella) is having its first performance at the end of July at the Australian Festival of Chamber Music in Townsville.