We sit on plastic chairs under strips of fluorescent lighting. Spread across the tables are large sheets of butcher’s paper, sticky notes and a paper cup full of pens. Twenty-one of the thirty people who registered to attend are here in East Geelong to talk about housing.

The facilitator says she’s sorry there’s no tea and coffee in the room because the urn is fixed to the wall in the kitchen out the back, but she encourages us to duck out and help ourselves to a cuppa. She apologises that the staff from the Department of Social Security will be late because their plane was delayed by Canberra fog.

This modest Monday afternoon gathering in a suburban hall in East Geelong is the first of twenty public consultations — or “community conversation forums” — to help the federal government draft a national housing and homelessness plan.

There is a lot riding on the process. As Chris Martin from the City Futures Research Centre at UNSW has pointed out, Australia has never really had a national housing strategy. What we have had, he told a recent online forum organised by National Shelter, is a series Commonwealth–State agreements regulating how much housing money flows to the states and what Canberra expects in return. Starting in 1945, those multi-year agreements have focused solely on social housing and homelessness; a bigger vision of how housing fits into the economic and social life of the nation has always been lacking.

Martin hopes the new national plan will be more ambitious in scope and help to end the fragmentation of policy within and between different levels of government. He wants to see housing integrated with other policy areas, including employment, welfare, immigration, urban development, climate change, disability and closing the gap.

But the issues paper designed to kick off our “conversation forum” in Geelong is not a promising start. Like many earlier housing inquiries, it seems to assume that Australia’s complex housing challenge has a simple answer — just build more dwellings. It foresees a happy land where homes are available, and affordable, for all. All that’s blocking the way is restrictive zoning, onerous planning processes, cumbersome building regulations and constraints on the release of land. Cut through that thicket of regulation and our destination is within reach.

This popular supply-side explanation to our housing problems was evident at August’s national cabinet meeting, where the states and territories agreed to build 1.2 million new homes over five years from 2024. That’s 200,000 more than the target announced just ten months earlier under the National Housing Accord.

As an incentive to meet this stretch target, Canberra pledged an extra $3 billion to fund $15,000 bonus payments to the states for each additional dwelling. Another $500 million was set aside to “kick-start housing supply in well-located areas” by delivering public services and amenities or bolstering planning capacity. State and local governments will vie for this money under a competitive funding program.

Anthony Albanese calls it “the most comprehensive housing strategy that we’ve seen for a generation.” Even if that’s true, it’s hardly a big claim. With a limited exception during the Rudd years, when Tanya Plibersek was minister, federal governments have dodged responsibility for housing for decades.

Still, the Grattan Institute reckons the prime minister is right to talk up the new deal. It calculates an extra 200,000 homes could make rents 4 per cent lower than they would be otherwise. Its researchers argue that “state and local governments… restrict medium- and high-density developments, largely to appease existing residents in established suburbs.”

Denita Wawn from Master Builders Australia agrees. Welcoming the national cabinet announcements, she said Australia needs to reform planning, zoning, and building approvals to ensure that we’re “not just going out in the suburbs, but up as well.”

In the hope of slicing through the red tape strangling our housing dreams, national cabinet also agreed to a National Planning Reform Blueprint to promote “medium and high-density housing in well-located areas close to existing public transport connections, amenities and employment.”

Rather than a blueprint, though, this is a vague grab bag of sometimes conflicting proposals. While it aims for more timely development approvals, for instance, it also wants to rectify “gaps in housing design guidance and building certification to ensure the quality of new builds.” And while it wants stronger “call-in powers” for state planning ministers it also favours better “community consultation processes.”

Victorian premier Daniel Andrews has already committed Victoria to reducing the role of local councils in significant planning decisions. Yet his government’s record inspires little confidence that this will dramatically boost supply. There’s been little action on a 2017 plan to devote surplus government land to new housing, and the state government can be just as sensitive to resident opposition as local councils are.

Examples can be found in electorally significant sandbelt seats in Melbourne’s southeast. After Kingston Council refused in 2018 to rezone a disused golf course to allow Australian Super to build more than 800 dwellings, the state government intervened and commissioned an independent inquiry. Two years after it reported, its recommendations are still under consideration.

Then there’s what locals call the Great Wall of Frankston. Developers proposed two apartment buildings side by side overlooking Frankston beach — one fourteen storeys high and the other sixteen. The council approved a development overlay that would have allowed twelve storeys. The matter was before the Victorian Civil and Administrative Appeals Tribunal when planning minister Sonya Kilkenny intervened and imposed interim controls to reset the height limit to just three storeys.

National cabinet’s blueprint also calls for states to “consider” the “phased introduction” of inclusionary zoning, which would force developers to incorporate social and affordable housing in any major project — a common practice overseas. The caveat is that this should be done “in ways that do not add to construction costs.”

It’s hard to see such a limply worded proposal generating much change. In 2022, Victoria sought a similar outcome by requiring developers building three or more dwellings to contribute to a social housing growth fund. In the face of property industry opposition, and claims this would push up the cost of buying a home, the proposal was scrapped within a fortnight.

The national planning reform blueprint appears to draw inspiration from work by the Productivity Commission, including a 2021 information paper identifying planning and zoning reforms and last year’s review of the National Housing and Homelessness Agreement. Both reports argue that reforms to planning, zoning and land release are crucial to increasing the supply and affordability of housing.

Many of the Productivity Commission’s recommendations make sense. Its call for state and local planning to be more closely aligned is a good example: a state-wide housing target has little point if local councils refuse to accept their share of new builds or greater density. The commission also wants fewer and broader land-use zones, permitting a wider range of activities without explicit council approval or costly variations. This would make it easier to have mixed developments that combine business, retail and housing.

But a close reading of the commission’s work reveals that many proposals in national cabinet’s planning blueprint are already in train. To varying degrees, all jurisdictions have been “streamlining approval pathways,” especially for significant projects, often by replacing council decision-makers with expert panels. State and local governments have also put considerable energy into removing “barriers to the timely issuing of development approvals.”

In other words, state and territory governments have been reforming planning for a long time without any appreciable effect on housing affordability. As Sydney University planning expert Nicole Gurran points out, more than 90 per cent of multi-unit development applications in New South Wales are approved and decisions issued within about three months.

Nor is there great evidence of planning and zoning being a significant brake on development. Australian Bureau of Statistics data show that more than a million dwellings were completed between December 2017 and December 2022. So, the government’s original Housing Accord target of one million new homes over five years only seeks to match what went before.

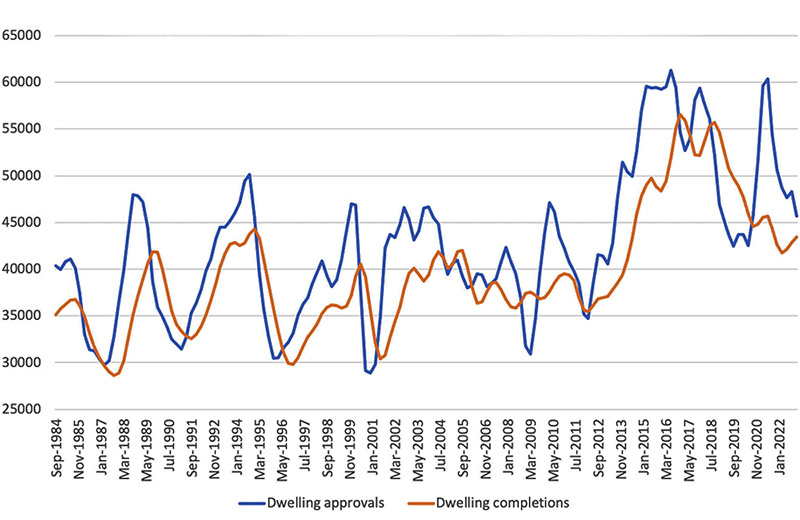

An anticipated decline in prospective construction activity has less to do with planning, zoning and land release than with the cyclical nature of the property industry. As this chart shows, the industry is characterised by peaks and troughs. What is more, dwelling completions lag, but rarely match, dwelling approvals. Considerably more housing gets approved than gets built, which points to factors other than planning influencing the supply of housing.

Dwelling approvals and completions 1984–2022

Source: ABS, 8731.0 Building Approvals, Australia and 8752.0 Building Activity, Australia

Among the factors currently dampening activity are higher interest rates, subdued consumer sentiment, weather problems, labour shortages, increased construction costs, bottlenecks in the supply of building materials and construction firms going bust. On top of all that, the Covid-era stimulus brought forward construction that would otherwise have occurred later. None of these adverse factors will be fixed by planning and zoning reform.

Even in a blue-sky world of light-touch regulation, devoid of constraints on labour and materials, a rational developer would avoid bringing so much housing to market that prices would fall, cutting their profit margins.

When I was researching my book about housing in 2018, I visited the 1000-lot Madora Bay development in the growth region of Mandurah south of Perth and chatted to a bored estate agent flogging house-and-land packages. He told me he would get in strife if he clocked up too many sales. His instructions were to sell a certain number of blocks each year, and no more, to keep a floor under prices.

A recent study suggests Madora Bay is not an isolated case. Prosper Australia examined the sales history of nine master-planned communities in three states and found a striking pattern. Sales peak in the early years when a greenfield development is just getting off the ground. But as the project matures, the sales rate slows, even though there is still plenty of land available and demand for new housing has not diminished.

Take the example of Woodlea, a 711-hectare estate twenty-nine kilometres northwest of the Melbourne CBD that will eventually be home to about 20,000 people. When the first of its 6500 lots were released in 2015, sales were brisk, and over the next two years about 14 per cent of the total development was sold — an average of forty-five properties each month. But then sales slowed substantially, even though land prices were still climbing fast. Over the next three years, only about 6.5 per cent of the total lots were sold — an average of just thirteen properties a month.

“Supply effectively reduced from February 2017 all the way through to January 2020, despite rising prices,” writes Prosper economist Karl Fitzgerald. He infers that Woodlea’s developers needed to wind back supply “for fear of price reductions.”

The property industry is one of the loudest voices calling for more land releases and looser planning and zoning rules, arguing that this will enable them to increase supply and reduce the price of housing. But Fitzgerald says this isn’t how property markets operate and it’s illogical to expect private developers to bring on excess supply and, in effect, undercut their own product.

It isn’t just on the suburban fringe that approved residential developments are slow to manifest as dwellings for sale or rent. In July 2015 developer Sterling Global bought the Australian Federal Police building on La Trobe Street in central Melbourne for $70.7 million. Plans were approved in November 2016 for a 70-storey tower including a hotel and 488 apartments. But Sterling Global instead sold the site to Mirvac for $122 million dollars (booking a 73 per cent capital gain in three years) in 2018. In June 2021, the City of Melbourne endorsed new plans for a 31-storey office complex. Construction was due to commence in 2022 but there is no sign of work. The AFP has moved out and the existing five-storey building now sits empty.

UNSW housing expert Professor Hal Pawson advises scepticism about housing strategies based solely on the belief that regulations are limiting building activity. “In reality,” he writes, “the prime consideration for private developers and their financial backers is expected market conditions when constructed homes are saleable.”

The Planning Institute of Australia also points out that planning “doesn’t control the speed with which housing is developed — nor affect powerful drivers for investment in housing.”

“It is simply wrong to say that planning is what is holding back our housing supply,” urban planner Marcus Spiller told National Shelter’s online forum. Yet he says this is the “intellectual architecture” underpinning the government’s approach to a national plan.

The founding partner of SGS Economics and Planning and former national president of the Planning Institute of Australia, Spiller is a veteran of Australian housing debates and has served on numerous state and federal boards and advisory committees. In his view, it is fanciful to assume that we can deregulate planning and then rely on competitive markets to meet the housing needs of low- and middle-income Australians. There is no trickle-down solution to the housing crisis, he says, and government and public policy must play a much stronger role.

If governments had kept building social housing at the same average rate as between 1955 and 1985, Spiller calculates, then Australia would now have 330,000 more homes for low-income earners. Instead, we shifted to providing rent assistance so tenants could find the housing that best suits them in the private market. The theory was that they would become masters of their own destiny. “It’s a compelling economic proposition that we have been pursuing for thirty or forty years,” says Spiller. “And I think it’s time to ask the question, has it worked?”

Clearly, it has not. Barely one in a hundred rentals is affordable for essential workers in full-time jobs, hundreds of thousands of households are forking out more than half their income on rent, and vacancy rates are at record lows. But the conventional supply-side wisdom can never be disproven. If there’s not enough housing or if housing is too expensive, then that must mean we have not yet deregulated enough, and must deregulate more.

In May this year former Reserve Bank economist Tony Richards published a long article in the Australian Financial Review describing how to solve Australia’s housing crisis. Despite the Financial Review’s simplistic spruiking — “1.3 Million Missing Homes Blamed on Councils and NIMBYs” — it is a complex and thoughtful examination of the issues. Richards recognises the need to build more social housing and acknowledges that we could use the tax system to moderate demand. But I was struck by what Richards does and doesn’t say about one of the local governments he picked out as anti-development.

Like all Sydney councils, Hunters Hill must develop a local housing strategy. Astonishingly, though, the council projects that this relatively low-density area just six kilometres from the GPO will lose population between now and 2036. Richards concludes that getting more medium-density housing in such a well-located area may mean taking powers away from local councils, so decisions are not just based on “the preferences of current residents, including NIMBYs,” but also encompass “the needs of the broader city and of future generations of potential residents.”

Richards commends the work of economist Peter Tulip from the Centre for Independent Studies, who has made a detailed analysis of apartment development in local government areas in Sydney and concludes that units are not being built where they are most wanted. Parramatta, for example, is increasing in density much more rapidly than Randwick.

Tulip says we should “build more housing where people want to live, as judged by their willingness to pay for a location.” Mosman is more expensive than Penrith, therefore also more desirable, and so that’s where we should build more apartments — and if we did, this would bring down prices there.

I have very little argument with this line of reasoning, and I think Tulip’s suggestion of a carrot-and-stick approach requiring councils to meet predetermined housing targets is worth pursuing — though Boris Johnson’s efforts to impose mandatory building targets in Britain quickly shattered when worried backbench MPs rebelled against forcing new developments on their wealthy constituents.

And this is what I think is missing from the Richards–Tulip analysis. It fails to draw the connection between housing and wealth. Tulip recognises that “planning restrictions reflect a desire for social exclusion” — that is, rich people want to live near other rich people and not near poor people — but he fails to consider that planning restrictions may also reflect the political power that wealth brings. Perhaps a more progressive income tax would generate a more egalitarian planning regime.

Or perhaps planning is not the issue. Analysing census data in the United States, Seth Ackerman finds a much stronger correlation between housing costs and household incomes than between housing costs and planning restrictions: “Rents and land values in a particular location are determined by the income and wealth of the people and businesses in and around that location. Put plainly, it’s the presence of rich people that makes rents expensive: they can pay more.”

Nor does a conventional supply-side approach concern itself with the fact that rich people generally consume more housing. As British housing economist Geoff Meen observes, housing demand comes “not just from newly forming households, but also existing households as incomes rise.” We need to consider the distribution of housing as well as supply.

“What happens when you build and you have no plan to distribute the housing to people who need it is wealthy people use more housing,” says Maiy Azize from the Everybody’s Home campaign. “They live in smaller households and they buy second homes.”

Excess consumption of housing by the rich pushes up prices for all, but this demand side of the housing equation is rarely mentioned. If we want to promote more efficient use of housing — like people living in apartments instead of freestanding homes with empty bedrooms — then changing how we tax housing and land could make a real difference.

Of course, planning and zoning matter in housing, but not necessarily as barriers — at least not in the way they are normally presented. They can also help overcome systemic problems.

When the Albanese government emphasises the need to build “well-located homes” or Denita Wawn from Master Builders talks about going up in the suburbs as well as out, they are responding to a major problem, often summarised as the “missing middle,” something Richards also identifies in his piece for the Financial Review.

The “missing middle” is primarily a reference to the lack of medium-density apartment dwellings of three or four storeys — the midpoint between high-rise towers and detached family homes. But it can also be applied spatially, to designate the lack of significant new construction in middle-ring suburbs.

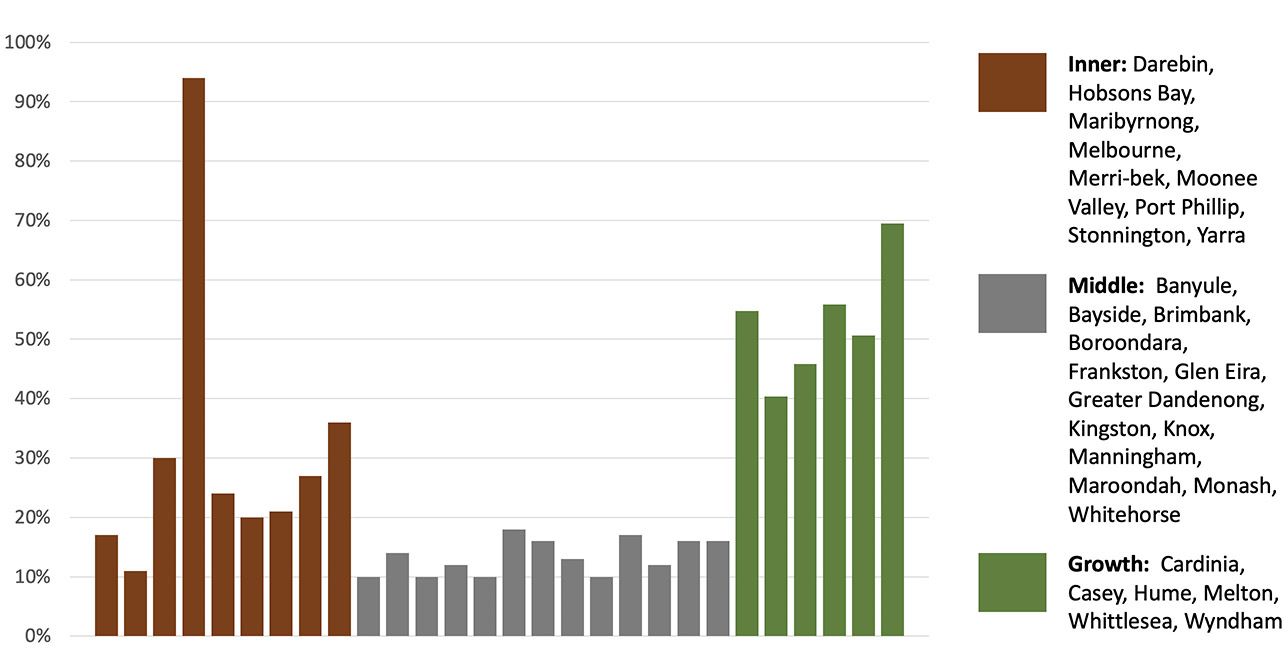

A quick summary of where new housing has been built in Melbourne in the past decade illustrates the issue. Between the 2011 and 2021 censuses, dwelling supply in Melbourne’s nine inner-city councils — members of the M9 alliance — increased by about a third. In the City of Melbourne, housing supply almost doubled in that time, from 53,000 to 103,000 dwellings, as new high-rise residential towers sprouted up across the Hoddle grid, Southbank and Docklands.

The supply of housing on the urban fringe rose by more than 50 per cent over the decade, mostly in the form of detached housing in residential developments on former farmland. But the supply of housing in Melbourne’s middle- and outer-ring suburbs grew by just 13 per cent. These are the “well-located” suburbs that the government is targeting for newer denser housing because they have good access to public transport, services, jobs and amenities.

Percentage of dwellings added in Melbourne local government areas 2011–21

Author’s calculations based on ABS Census data

These suburbs might have the most restrictive planning regulations and the most vociferous and well-heeled resident action groups. But I suspect something else is at work.

Unlike central Melbourne, these suburbs don’t have brownfield sites — disused docklands or railyards that can be home to high-rise residential towers. Unlike inner-city Fitzroy, Brunswick or Footscray, they have few warehouses or workshops that can be redeveloped into medium-density apartment blocks. And unlike the city’s outer-urban growth areas, no greenfield sites are available to be transformed into housing estates.

Melbourne’s middle- and outer-ring suburbs are sometimes called “greyfields.” They are, characteristically, residential neighbourhoods dominated by detached homes on separate blocks, with little in the way of industry. That makes urban regeneration challenging, even as buildings age and are due for replacement. Without strategic planning, redevelopment generally takes the form of piecemeal infill — a single family home is demolished to make way for two or perhaps three townhouses. Gardens and trees give way to garages and driveways. Density is increased but the amenity of suburban life is diminished with little planning for the extra demand on services, roads and public transport. No wonder existing residents object to new developments.

More than a decade ago, researchers Shane Murray and Peter Newton identified more than a quarter of a million middle-suburban properties in Melbourne with “high potential for regeneration, in localities where residential building stock is failing and infrastructure is in need of upgrade.” But the historical pattern of residential development based on freestanding houses on separate titles makes it very hard to assemble parcels of land big enough to carry substantial redevelopment projects — the “missing middle” of European-style medium-density housing. This challenge will be even greater in future decades, when current growth areas with smaller lot sizes are ripe for redevelopment.

The Planning Institute of Australia puts its finger on the problem: “many of the easiest candidate sites for housing development are already spent.” It calls for governments to take a leading role in land markets to overcome the inefficiencies caused by fragmented ownership. What’s required to address the “missing middle” is not for governments to get out of the way but for them to intervene more to assist private capital to carry out high-quality, precinct-level redevelopment.

Melbourne, says Marcus Spiller, needs to add one extra dwelling for every existing 1.3 dwellings over the next thirty years, all within the existing urban footprint, “a level of transformation that is difficult to wrap your head around even as a professional planner.” We won’t achieve that with the “hunt and catch, opportunistic, fragmented approach that we’ve had until now,” he says. “The real issues with housing supply lie in land withholding, land assembly, insufficient infrastructure and land fragmentation, all of which require concerted policy effort and public intervention.”

Chris Martin agrees. In a report for the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, Martin and his co-authors call for a mission-oriented approach to the national housing strategy. Drawing on the thinking of leading economist Mariana Mazzucato, they argue that the state must play a larger role in “innovation and value creation” and “actively create and shape markets.” Rather than a level playing field in which market can compete, Mazzucato says the state should tilt the playing field towards achieving publicly chosen goals.

The mission, says Martin, can be plainly stated: everyone in Australia needs adequate housing.

We reach a similar conclusion in the community hall in East Geelong. The first session is focused on social housing and homelessness, and our initial task is to share three words to describe what a new national housing plan should achieve. An app collates our responses and projects a word cloud dominated by concepts like affordability, safety and security.

Many of my fellow participants work in public and community housing. They are deeply knowledgeable, their comments detailed and passionate. They talk about renters in the private market needing help to hold on to tenancies — it’s better to support someone in housing than see them slip into homelessness. Yet so many services only kick in after someone is in crisis.

They talk about the lack of emergency housing, about mouldy homes, and about extending Victoria’s approach to domestic violence to the rest of the country — it is the only state that has a policy of removing the perpetrator from the home, regardless of who holds the lease. And they talk about the burgeoning number of applications on the priority list for social housing — 7000 in the Barwon region alone.

After ninety minutes, the top half of our sheet of butcher’s paper is a cluttered jumble of coloured sticky notes. This is where we’ve been asked to identify challenges in addressing homelessness and improving access to social housing. The lower half — where we’ve been asked to identify what is working well — is more thinly populated.

Afternoon has turned into evening and it’s time for a break. Fresh fruit and an abundant supply of traditional baked goods compensate for soggy sandwiches. I load my paper plate with lemon slice and hedgehog and buckle down for another ninety minutes of discussion, this time on housing markets. Our numbers have shrunk from twenty-one to ten.

I am the first to speak and express my dismay that the government’s issues paper makes only passing references to tax, most of them referring to recent changes to promote the build-to-rent sector. The paper ignores debates about the relative merits of stamp duty and broad-based property taxes, and makes no mention of negative gearing, the capital gains tax discount or the exemption of the primary residence from the pension assets test — generous tax concessions that encourage property speculation and over-investment in housing.

The facilitator writes notes and thanks me for my contribution. A few others in the room offer supportive comments. But when we eventually disperse I wonder whether our views, falling outside the parameters of the “issues” offered for discussion, will make any impression on the final consultation paper developed from all these community forums. •