The fifty-year anniversaries of the Vietnam war — America’s greatest strategic blunder of the twentieth century — keep arriving. January marked the signing of the Paris Peace Accords in 1973, March commemorated the departure of the last American combat soldier from Vietnam, and this month was the fiftieth anniversary of the Nobel Peace Prize awarded to Vietnam’s Le Duc Tho and the United States’ Henry Kissinger for negotiating the ceasefire.

Amid those anniversary moments, US president Joe Biden flew to Vietnam in September, the fifth sitting American president to visit since Bill Clinton re-established diplomatic ties in 2000 and “drew a line under a bloody and bitter past.”

In Hanoi, Biden and Communist Party general secretary Nguyen Phu Trong “hailed a historic new phase of bilateral cooperation and friendship,” creating a strategic partnership that expressed US support for “a strong, independent, prosperous, and resilient Vietnam.”

With such flourishes, history delivers irony garnished with diplomatic pomp. Expect many shades of irony in April 2025, the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the war, when Saigon fell to North Vietnamese forces. (Note the way the war is named: Australia joins America in calling it the Vietnam war; the Vietnamese call it the American war, the concluding phase of a thirty-year conflict.)

The shockwaves that ran through Asia after the second world war were driven by geopolitical fears that imagined nations as dominos toppling into communism. As France fled Indochina and Britain retreated from Southeast Asia, the United States stepped in to stabilise what it saw as a series of tottering states in Southeast Asia.

The proposition that the Vietnam war was “fought for, by, and through the Pacific” was the focus of a conference at Sydney’s Macquarie University that is now a book with nineteen chapters from different authors.

The editors of The Vietnam War in the Pacific World, Brian Cuddy and Fredrik Logevall, describe a wide gap between US rhetoric and the military reality of the region. The US claimed it was acting to save the whole of Southeast Asia, they write, but “the documentary record suggests that Washington lacked a suitable appreciation of how the war in Vietnam was linked to the politics of the wider region.”

In a chapter on “the fantasy driving Australian involvement in the Vietnam war,” the historian Greg Lockhart, a veteran of the war, writes that the “red peril” rhetoric of the Menzies government “disguised its race-based sense of the threat from Asia.” By 1950, he writes, Australian policy had been shaped by an early British version of domino thinking and the “downward thrust of communist China,” a thrust that linked the perils of geography to the force of gravity.

Just before the defeat of French colonial forces at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, US president Dwight Eisenhower proclaimed the fear that drove US policy: “You have a row of dominos set up, you knock over the first one, and what will happen to the last one is the certainty that it will go over fairly quickly.” The theory held that the Vietnam domino, with pushing by China, would topple the rest of Indochina. Burma and Malaya and Indonesia would follow. And then the threat would cascade towards Australia and New Zealand.

Lockhart scorches the way these fears led Australia to Vietnam:

Between 1945 and 1965, no major official Australian intelligence assessment found evidence to support the domino theory. Quite the reverse, those assessments concluded that communist China posed no threat to Australia. Shaped by the geographical illusion that “China,” or at least “Chinese” were “coming down” in a dagger-like thrust through the Malay Peninsula, the domino theory was the fearful side of the race fantasy, the nightmare that vanished once it had fulfilled its political function.

The US strategic ambition of containing communism in Asia “had been very largely achieved before the escalation of US forces in Vietnam in 1965,” Lockhart concludes, because Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, the Philippines and Indonesia were already “anti-communist nation-states.”

The same quickly became true of Indonesia, where the military takeover in 1965 was a decisive shift towards the United States, destroying the largest communist party outside the Eastern bloc. Yet US president Lyndon Johnson used Indonesia to proclaim what American historian Mark Atwood Lawrence calls “the domino theory in reverse.” LBJ’s argument by 1967 was that the Vietnam war was necessary as a “shield” for a virtuous cycle of political and economic development across Southeast Asia.

Lawrence laments that few in Washington followed the logic that “Indonesia’s lurch to the right, far from justifying the war in Vietnam, made that campaign unnecessary by successfully resolving Washington’s major problem in the region.” He cites evidence to a Senate committee in 1966 by a legend of US diplomacy, George Kennan, that events in Indonesia made the risk of communism spreading through the region “considerably less.”

In 1967, the US Central Intelligence Agency appraised the geopolitical consequences of a communist takeover of South Vietnam. Lawrence says a thirty-three-page report “concluded that the US would suffer no permanent or devastating setbacks anywhere in the world, including even in the areas closest to the Indochinese states, as long as Washington made clear its determination to remain active internationally after a setback in Vietnam.” The study, as he observes, had no discernible impact on LBJ’s thinking. Instead, Washington stuck with its “iffy” and “problematic” assumptions about falling dominos and the interconnections among Southeast Asian societies.

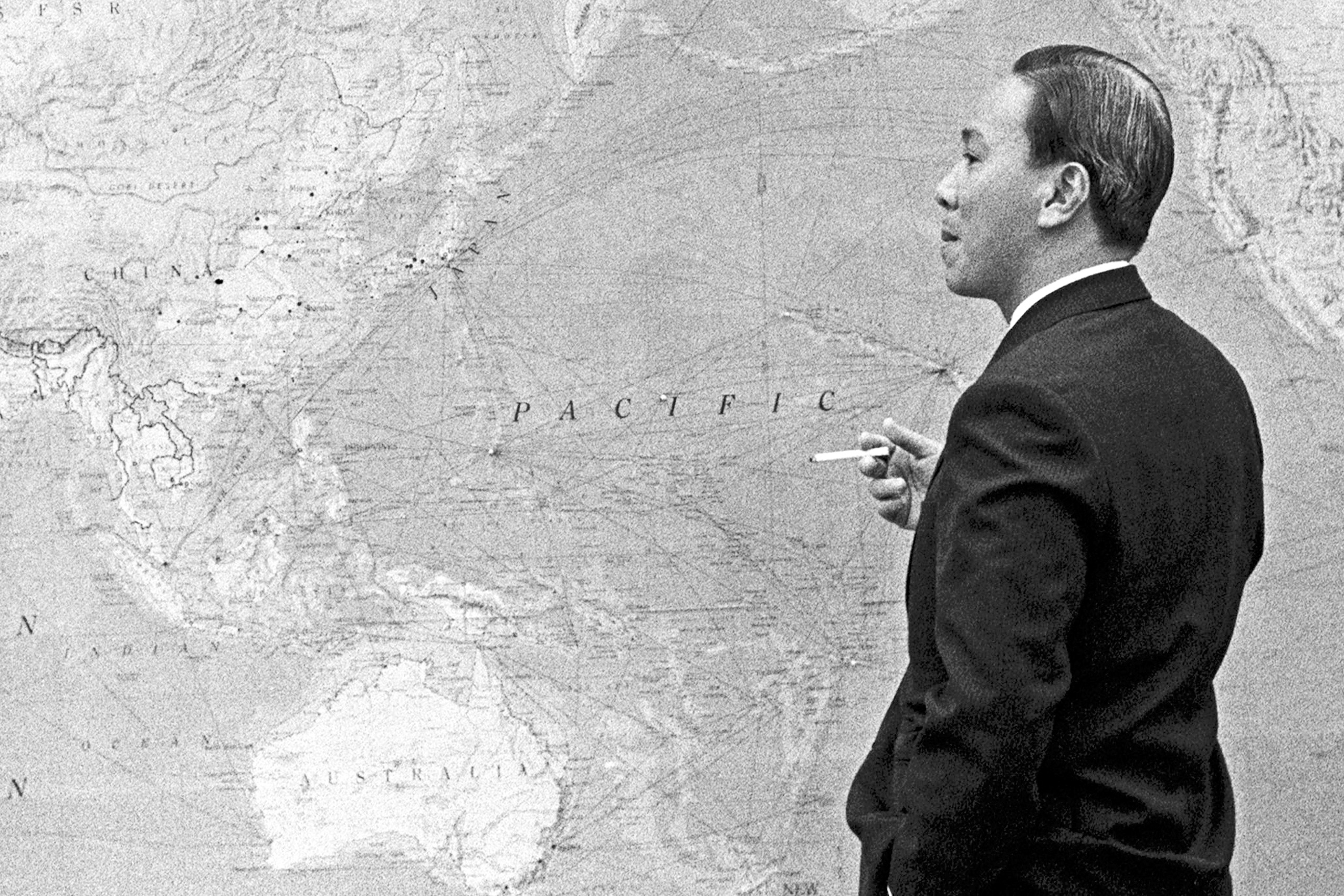

For the new nation of Singapore, separated from Malaysia in 1965, the era offered the chance to build links with the United States and hedge against bilateral troubles with Malaysia and Indonesia. S.R. Joey Long writes that prime minister Lee Kuan Yew used Washington’s Vietnam focus to cultivate America for both weapons and investment: “The inflow of American military equipment and capital enhanced the Singaporean regime’s capacity to defend its interests against adversarial neighbours, further its development strategies, distribute rewards to supporters, neutralise or win over detractors, and consolidate its control of the city-state.” A later chapter quotes a CIA report in 1967 that 15 per cent of Singapore’s gross national product came from American procurements related to the war.

During his long leadership, Lee Kuan Yew always proclaimed the one remaining vestige of an argument for the US war — the “buying time” thesis, which claims that the US provided time for the rest of Southeast Asia to grow strong enough to resist domino wobbles.

Mattias Fibiger’s chapter on buying time calls the idea a “remarkably durable” effort to transmute US failure into triumph. What president Ronald Reagan later called a “noble cause” is elevated to a constructive breathing space. “America failed in Vietnam,” according to the Henry Kissinger line, “but it gave the other nations of Southeast Asia time to deal with their own insurrections.”

From 1965 to 1975, the region “became far more prosperous, more united and more secure,” Fibiger notes, and he finds “some truth to the claims that the Vietnam war strengthened Southeast Asia’s non-communist states, stimulated the region’s economic growth, and led to the creation of ASEAN — all of which left the region more stable and secure.”

The creation of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in 1967 (with an original membership of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand) is a milestone in the region’s idea of itself. ASEAN’s greatest achievement is to banish — or bury deeply — the danger of war between its members. This is region-building of the highest order. Earlier attempts at regional organisation had failed. Indeed, Fibiger notes, conflict seemed so endemic that a 1962 study was headlined, “Southeast Asia: The Balkans of the Orient?” ASEAN has helped lift the Balkan curse.

The founders of ASEAN certainly looked at Vietnam and knew what they didn’t want. While the war inspired “fear of American abandonment,” Fibiger thinks any relationship between the conflict and the strength of the region’s non-communist states is indirect. American military actions had little bearing on the ability of governments outside Indochina to command the loyalty of their populations.

Commerce, not conflict, became the region’s guiding star. In the quarter-century after 1965, the economies of East and Southeast Asia expanded more than twice as quickly as those in other regions. The eight “miracle” economies — Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand — grew more prosperous and more equal, lifting huge numbers of people out of poverty.

Fibiger writes that the Vietnam war served as an engine of economic growth in Southeast Asia and fuelled exports to the US market. Growth legitimised rather than undermined authoritarian regimes in ASEAN, and deepened oligarchy. The war, he says, helped create strong states, regional prosperity, and ASEAN.

Beyond that summation, Fibiger attacks the buying time thesis as morally bankrupt because it is a metaphor of transaction, “implying that the Vietnam war’s salutary effects in Southeast Asia somehow cancel out its massive human and environmental cost in Indochina.”

America’s allies joined the war to serve alliance purposes with the United States. South Korea sent 320,000 troops to South Vietnam between 1965 and 1973, Australia 60,000, Thailand 40,000 and New Zealand 3800. The Philippines contribution was a total of 2000 medical and logistical personnel. Taiwan stationed an advisory group of around thirty officers at any one time in Saigon but sent no combat troops for fear of offending China.

For their part, Australia, New Zealand and South Korea fought “not for Saigon,” writes David L. Anderson, “but in keeping with their established practices of protecting their regional interests and constructing their national defence with allies.” By 1970, Australian opinion was divided over the war, Anderson notes, but the alliance with the United States still had popular support:

The war polarised the politics of the US, Australia and New Zealand. Antiwar sentiment in the three countries did not alone bring an end to their military engagement, but protest movements conditioned the political process to accept negotiation and withdrawal when government strategists decided national security no longer required the cost and sacrifice of the conflict.

In the years after the Vietnam war, Anderson says, the former junior partners maintained friendly relations with Washington even though the United States “was seen as a less reliable partner.” The new need was “greater self-reliance and independence from the US.”

Editors Cuddy and Logevall conclude that studying the regional dynamics of the Vietnam war is not purely of historical interest: “American foreign policy is turning its attention — even if haltingly and haphazardly — back to the Pacific… Understanding how the region reacted to the American war in Vietnam and how the war changed the region might help the United States and its Asia-Pacific partners navigate the currents of competition in the future.”

The Vietnam history offers cautions about the new competition between the United States and China. The United States again seeks regional allies and is gripped by vivid fears about the threat China poses to the system. The region again ponders the level of US commitment and its reliability.

The two giants compete to hold friends close and ensure no dominos fall to the other side.

Vietnam is a haunting demonstration that the Washington consensus can misread or even obscure Asian understandings and the complex politics of the region. Those truths from history matter again today. As America’s greatest strategic blunder of the twentieth century was in Asia, so in this century America’s greatest strategic challenge is in Asia. •

The Vietnam War in the Pacific World

Edited by Brian Cuddy and Fredrik Logevall | University of North Carolina Press | US$29.95 | 382 pages