One day in March 2008 Rupert Murdoch was sitting in a plane on the tarmac in Florida when news broke that New York governor Eliot Spitzer had been caught in a scandal involving prostitutes. News Corp’s executive vice-president Gary Ginsberg, also on board, watched as his boss rang Col Allan, the Australian editor of the New York Post. Murdoch was “rubbing his hands together” as he excitedly told Allan, “This is going to be the greatest headline of all time.” After having “so much fun” discussing options, says Ginsberg, they finally settled on the page one splash, “HO NO!”

Okay, maybe it wasn’t the greatest headline. The paper’s infamous “Headless Body Found in Topless Bar” was always going to be tough to beat. But it was a classic Murdoch moment. It revealed not only his lifelong obsession with gossip and scandal but also the pleasure he gained from bursting the bubble of the powerful and famous. It also showed just how much he loved rolling up his sleeves and being part of the action of making the news.

The New York Post wasn’t Rupert Murdoch’s first acquisition in the United States, but of all the American media outlets he’s purchased it is arguably the most important. It was where he refined his version of tabloid journalism for the American market. It was his entree to the Big Apple, where much of America’s media was headquartered, and meant he got noticed nationally. And it was the forerunner of Fox News and the complement to his later purchase of the Wall Street Journal, which meant it was where he learnt how to wield power in the United States.

So it’s no surprise that Murdoch is all over Paper of Wreckage, Susan Mulcahy and Frank DiGiacomo’s new history of nearly fifty years of the Post, from 1976 to the eve of Donald Trump’s re-election in 2024. What is unexpected is that the book’s methodology — it’s based on 240 interviews with insiders and close observers — has created a repository of revealing Murdoch anecdotes probably only exceeded in size by the evidence to Britain’s Leveson inquiry into phone hacking.

Paper of Wreckage charts how a Democrat-leaning paper once owned by New York socialite Dorothy Schiff morphed into an organ of propaganda, scandal and retribution. It covers the period between 1988 and 1993 when Murdoch was forced by media ownership rules to relinquish the Post in order to create Fox as America’s fourth national TV network. And it details how Murdoch was allowed to buy the paper back after its interim owner, Peter Kalikow, was driven to bankruptcy.

Somehow Mulcahy and DiGiacomo have managed to wrangle all those voices into a coherent and compelling narrative. They have kept the main events in sight — mayoral races, the big stories, the influence of Trump and #MeToo — while taking lots of side trips down dark Manhattan alleyways to reveal crime and scandal and even the workings of the local Mafia.

The Post was founded by Alexander Hamilton in 1801. Yes, that Alexander Hamilton. It was the Evening Post back then, and it was still an afternoon paper when Schiff bought it in 1939. As a liberal Jew, Schiff was in sync with her mostly Democrat audience, albeit with some quirky habits. For example, when she appeared in the newsroom she was often followed by her chauffeur carrying her minuscule dog. (Meryl Streep’s character in the Devil Wears Prada was apparently based on “Miss Schiff,” as she was known despite churning her way through four marriages.) One of the book’s interviewees, former senator and NBA basketballer Bill Bradley, says he paid attention to what was written in the Post back then because Schiff treated the paper like a public service.

All that changed when Murdoch arrived. He was keen to make his mark in America, where he’d already bought a couple of newspapers in San Antonio, Texas, that weren’t strategically useful. When he settled on the deal, he set to work quickly. As the Post’s film critic, Frank Rich remembers, “Copy was being butchered. There was a kind of Hitler marching into Poland atmosphere.” It turned from what reporter Marsha Kranes described as “a writers’ paper,” where the words reporters wrote made it to print, to a paper in which the pages were planned and everyone “had to write to fit.”

Australian reporter Jane Perlez was already at the Post when Murdoch arrived. She had worked at the Australian under the small-l liberal editor Adrian Deamer until Murdoch fired him in 1971. Perlez says she loved the Post under Schiff. She got to do everything, from covering political conventions to writing literary interviews. When Murdoch turned up, her colleagues looked to her for answers. “What sort of owner would he be?” they asked. She tried to be upbeat because she didn’t want to crush their hopes, but as soon as Murdoch walked in she knew “the game was over.”

While one Aussie left, lots of others arrived, and almost none of them emerge from this book looking good. It’s safe to say that Murdoch’s first editor, Ted Bolwell, had very few friends. Interviewees describe him as truculent, arrogant, surly, red-faced, ghastly, terrible, “a disaster from day one,” vile, “a crazy person” and “a fucking idiot with an unbelievable temper.” Reporter Cheryl Bentsen recalls he had a curly perm and wore platform shoes, “which everybody found hilarious.” Bureau chief George Arzt remembers Murdoch telling him that Bolwell was a brilliant editor. “I didn’t want to tell Murdoch the guy’s nuts.”

Apart from Murdoch, the most famous Australian was Steve Dunleavy, the legendary drunkard who seemed to attract and repulse colleagues in equal measure. He broke rules, disregarded ethics, slept with half the newsroom and connived his way to get access to interviews. But for all his faults, says reporter Hal Davis, “he knew how to inspire his reporters. He had charisma and could be very persuasive.” Reporter Richard Esposito says that “Steve was a master of tabloid journalism. Drunk or sober.” According to associate editorial page editor Eric Fettmann, “his strength as a journalist was his tenacity, his willingness to do anything for a story. And his weakness was his willingness to do anything for a story.”

Then there was editor-in-chief Col Allan, recruited in 2001 from Sydney’s Daily Telegraph where his leadership style had earnt him the nickname Col Pot, a reference to the murderous Cambodian dictator Pol Pot. He was in charge of the Post for fifteen years and then, from 2019–21, was the paper’s “editorial adviser.” Interviewees acknowledge he “had cash register instincts for what people wanted to read and how stories were to be played” and even his critics admit he gave the paper “clarity and a road map” for covering 9/11, the city’s biggest-ever story. But they also claim Allan, who was madly pro-Trump, “would kill his grandmother for a story” and “was a miserable human being.”

Unlike Murdoch, Allan agreed to be interviewed for the book. His comments could be described as self-evident, because the racy, polarising pages of the Post had already spoken for him, but he does reveal what drove the paper’s coverage. For example: “I happen to believe in grudges. I happen to believe in getting square. I’m not one of these guys who likes to turn the other cheek and walk away. People fuck me I’m going to fuck them. It’s as simple as that. This is not small-town Tennessee here.”

Paper of Wreckage reinforces just how much Murdoch loves the gossipy, sleazy and cruel world of tabloid journalism. And it shows how the ethos he largely created had a real effect on both the paper and its people. Feature writer Joyce Wadler remembers sitting in the stairwell in tears because of what was happening to the paper she loved. “I was very happy until Murdoch came in. I could see the stuff I held dear — which was respect for writers, respect for facts — was going. They were chopping up stories and rewriting them, and they were uglifying the universe.”

Reporter Leslie Gevirtz recalls “there were certain tropes you followed. Every co-ed was pretty. Every cop was a hero. Every bad guy was a bad guy whether they were a bad guy or not.” Murdoch threw out traditions. It was okay to break embargoes in order to beat the main competitor, the Daily News. Reporters learnt that the game had changed, the norms were gone. Their job was to get the story first.

Murdoch was often directly involved. In March 1977 reporter Cheryl Bentsen was visiting Washington DC when members of an Islamist group took over the headquarters of the Jewish B’nai B’rith organisation. They killed two people and took more than a hundred hostage. Doing her best on deadline, Bentsen made some calls and phoned through what she had. The next day the front-page article had her byline but none of the words were hers. “It was filled with all kinds of made-up interviews as if I had gotten some hot scoop and had interviewed hostages and nurses. I was absolutely stunned.”

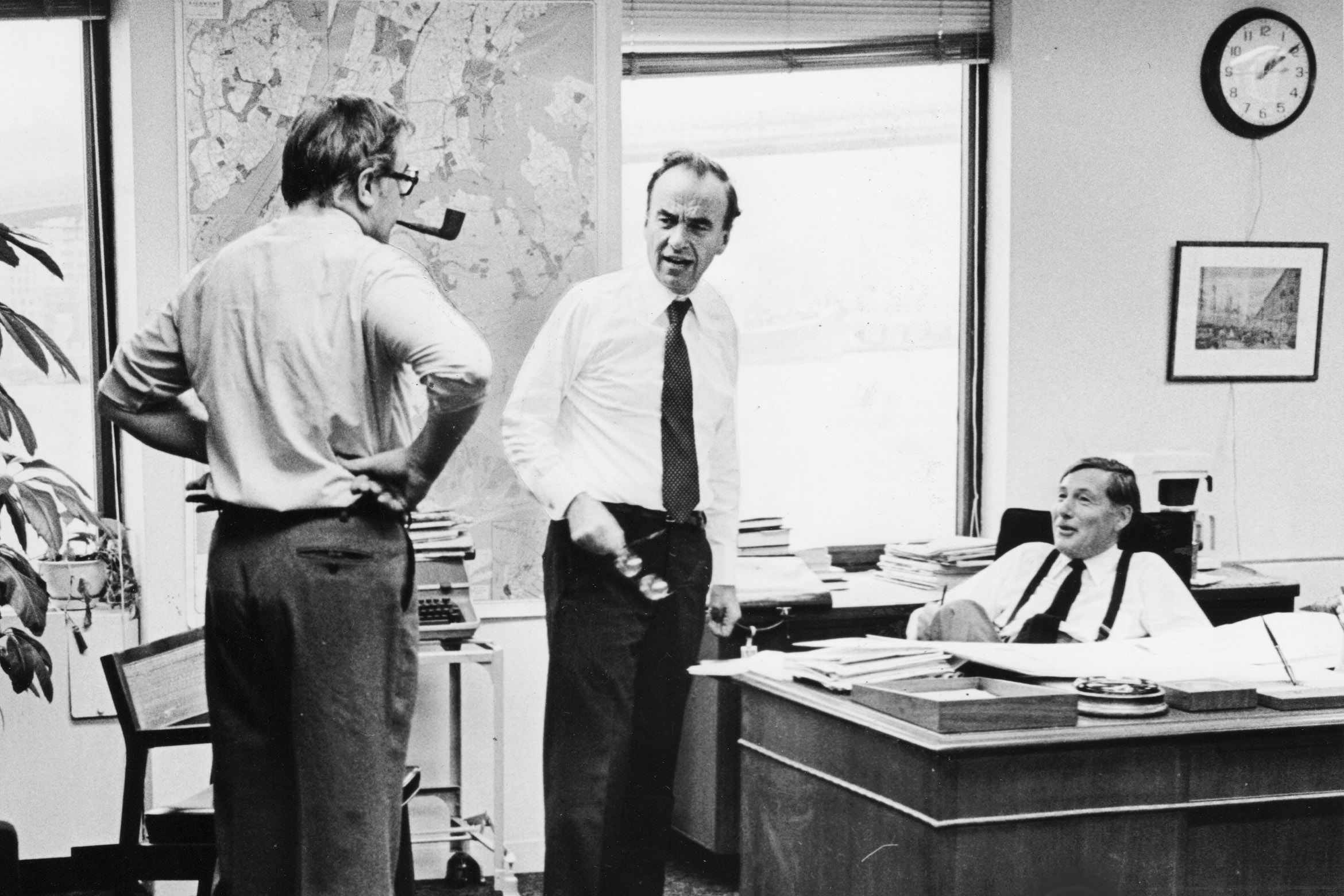

Demonstrating the value of the book’s approach, Bentsen’s account is verified by the next interviewee, former desk editor David Rosenthal, who witnessed what happened to the story back in the newsroom: “Murdoch came in himself at about 3.30 in the morning. We were all doing rewrites of wire stories and making calls. It was a scary situation. He ripped up every piece of copy and rewrote the front-page story himself. He also wrote this inflammatory headline (“WE’LL BEHEAD THEM”). He sat there at the desk, jacket off, with his suspenders, his tie loosened, banging out take after take on an old Underwood. We were all wondering, ‘What the fuck is he writing?’”

If this is true — and no one’s disputed it — it would be grounds for immediate dismissal for a reporter at any respectable newspaper. It’s the sort of behaviour associated with the infamous fabulist Jayson Blair who was drummed out of the New York Times for concocting quotes from bogus interviewees. At the New York Post, the proprietor, no less, is accused not only of committing this sin but also of signalling to his staff that it was okay to do likewise. As Rosenthal noted, “It wasn’t Kansas anymore. Everybody realised it by the next morning.”

There are other moments of dubious morality, such as the one recalled by David Schneiderman, the editor-in-chief of Manhattan’s counterculture paper Village Voice, which Murdoch also owned briefly. He remembers a meeting at which Murdoch, out of the blue, started boasting about the time he had hired somebody to spy on the owner of Britain’s Daily Mail, Lord Rothermere, and his girlfriend. “He was getting a huge kick out of telling stories about spying on these guys,” Schneiderman says, “and then he would let them know what he had found out, just to say ‘leave me alone, and I’ll leave you alone.’” It’s an observation hidden among many in this book, but it’s profound given everything we now know about phone hacking.

Employees like the Australian assistant managing editor Wayne Darwen took their cue from Murdoch. “He knew what a story was, and he knew how to tell it and how to sell it. And those who worked for him, who became loyal Murdochians, developed that same attitude. It didn’t matter if it was Ted Kennedy or Richard Nixon. If there was a scandal, it’s going out there, and you’re going to show no mercy. Don’t let anything get in the way of a good story.”

Having co-edited an oral history of newsroom culture myself, I know it’s difficult to get past the tales of chain-smoking drunkards behaving badly on deadline. It’s hard because the stories are often compelling and they’re told by lifelong storytellers whose work connects them with interesting people.

Nevertheless, I was searching for something more in this book. I was after the insiders’ inner thoughts, not just their colourful anecdotes. I wanted them to admit that what they did wasn’t always right — that sometimes it was just plain wrong. And I wanted to know what effects their work had on their targets, because often they humiliated people and prevented civil discourse about really important issues.

Maybe this was too much to ask. The culture at the Post wasn’t reflective. Most of the time, reporters were too anxious about their next story to think very deeply about the one they’d just written. As city hall politics reporter Tara Palmeri says, “I always went out on a story with a knot in my stomach, worried that if I didn’t bring back the goods, I was dead to them.” When reporters are desperate there’s not a lot of empathy for the subjects of their stories. They become collateral damage in the relentless grind of daily tabloid journalism.

Sometimes this seeming lack of empathy surfaces in throwaway comments. Palmeri, for example, admits she loves covering scandals. Darwen says writing the paper’s incendiary headlines is “like a game.” So the book leaves the critique largely to outsiders — people like New York human rights lawyer Ronald Kuby, who makes the point that “cute and clever” headlines don’t wash away the paper’s “race baiting” or “insistent demonisation of black youths” or “excusing of police brutality year after year.”

Paper of Wreckage covers young Donald Trump, the wannabe New York developer and media-driven narcissist. We see his interactions with reporters as he climbs the ladder and builds his brand. But the book doesn’t do justice to his first term in the White House or the 6 January insurrection or his four years in exile, probably because the insiders with the most to say are still working on the paper and therefore less free to speak openly, let alone critically.

Mulcahy and DiGiacomo do make clear the extent to which Col Allan shaped the paper’s pro-Trump coverage. On one occasion Allan even wore a MAGA hat in the newsroom. Mary Trump, niece of Donald Trump and author of the critical Too Much and Never Enough, concludes the Post was “the paper that gave him the most flattering and divorced-from-reality coverage.”

The book’s excellent treatment of events tends to taper off in the last hundred pages. It doesn’t mention Florida governor Ron DeSantis, even though the Post touted him as the future Republican nominee in November 2022 with the glowing page one headline “DeFUTURE.” Likewise, it barely covers the Covid pandemic, which had a devastating effect on New Yorkers, though one interviewee, Bill Bigelow, does draw a straight line between Murdoch and the most tragic effect of Trump’s first presidency.

Bigelow’s observation is not just a damning indictment of the paper’s coverage of one story but of Murdoch’s entire American endeavour: “Without Rupert Murdoch and the New York Post, there’s no Fox News. And without Fox News, in my estimation, there’s no Donald Trump, and without Donald Trump we don’t have all those people dead from Covid.” •

Paper of Wreckage: An Oral History of the New York Post 1976–2024

By Susan Mulcahy and Frank DiGiacomo | Atria Books | US$32.50 | 592 pages