Until last month Nvidia, the maker of the high-end semiconductors that underpin advanced artificial intelligence platforms, was among the handful of US technology stocks driving capital markets ever higher. But then it lost almost US$700 billion of its $3 trillion sharemarket value, a shock induced entirely by the emergence of a single Chinese AI platform. The ripples continue.

Leadership in AI has been a hallmark of America’s strategy to contain China. Joe Biden’s strategy was to limit the supply of chips, like Nvidia’s H-100, and the equipment used to make them. Then a small, lightly funded Chinese startup developed an evidently high-quality AI platform that may even be superior to those offered by Microsoft and other US majors.

The upstart, DeepSeek, was developed in a private incubator financed by a Chinese investment fund that uses AI to evaluate and rationalise often illogical investment patterns. It is based in Hangzhou, a prosperous city adjacent to Shanghai that has been trialling AI applications in various public services (including, notably, intellectual property disputes) for half a decade.

DeepSeek’s breakthrough lends weight to the late Harvard University economist Bill Overholt’s prediction a few years ago that American efforts to limit Chinese technological progress would be counterproductive. Based on what we know, the Chinese platform delivers a high-value result using relatively few of the American chips — and it does so up to fifty times more efficiently than existing platforms. (Among other things, that means a very large energy saving.) China was not supposed to be able to do this.

Another surprise — though maybe it shouldn’t be — is that Deep Seek is a private initiative, not the result of the publicly funded AI “stacks” proliferating across China. In fact, Overholt and others have observed that the central flaw in China’s economic strategy under president Xi Jinping has been its dependence on state-led innovation and capital and the inhibiting effect of a political preoccupation with stability and efforts to suppress private motivations.

Gone are the double-digit GDP numbers that for decades reflected China’s dynamic economy. The country is struggling with generational change — not just in terms of leadership, but also systemically: the economic model that drove growth has not only run out of steam, it has also created a burden that Beijing is trying to shed.

Xi, who looks like the leader no one will thank, might manage the necessary shifts successfully. Right now, though, he and China are in the deep end, paddling hard to avoid even more serious trouble — much of which is evident in the pile of debt accrued across the economy, but especially by local government.

If you find yourself in hole, stop digging. Xi Jinping stopped digging in August 2020, when China’s authorities issued the “three red lines” of financial regulation, which effectively ended the flow of debt fuelling China’s property markets.

The problem of excessive and rising debt was not new. But although it had been growing since 1994, it was boosted dramatically by the exigencies, first, of the global financial crisis and then, more recently, of the Covid-19 epidemic.

When you stop digging, you are still in a hole. Xi first flagged intervention back in 2017 when he told the nineteenth party congress that property exists to be lived in, not speculated on. But the challenge he faced was not limited to curbing speculation. Land dealing had become fundamental to the nation’s investment-driven growth. More particularly, revenues from selling land rights were underpinning the local government finances that drive as much as four-fifths of China’s economic activity.

China’s problem is not simply one of a “bubble economy,” in which asset prices and debt inflate in a mutually reinforcing style that, at some point, bursts. Rather it is problem made up of components fundamental to China’s political and economic system. Local government, industry policy, national savings, banking, welfare and social services, infrastructure and innovation policies are all integral to this mix. And, like all things China, this big, complex issue is hard to map, let alone interpret.

For anyone wanting to understand what has happened in the Chinese economy in recent decades and, to some extent, what is happening now, Lan Xiaohuan’s How China Works is a timely, insightful and generally accessible primer. Published in Chinese in 2021, it sold more than a million copies before its recent translation into English. Its author is an economics professor at Fudan University but I suspect his insights come from his role as strategy director in one of China’s largest industrial investment funds.

China’s Covid-19 suppression persisted through 2022, so Lan’s work doesn’t fully reflect the depth of problems created by what was, to a large extent, a prolonged national shutdown. Nor does it take account of the more stringent international trade sanctions that followed. Both factors exacerbate the complex, difficult challenge faced by China’s leadership: how to correct a system out of balance.

Lan offers a fascinating insight into how China’s political and economic system works, and especially why and how local government plays such a critical role, though Beijing maintains strategic control and guidance. He describes how an over-reliance on capital-intensive growth collided with a fundamental imbalance in economic management and political discipline. In short: local governments have huge accountabilities but limited revenues. Land therefore became a driver of the extra revenue that sustained debt-funded investments. In the end, the whole system — from local government to banking and industry — was infected with a false sense of stability and confidence.

Since Lan published, China’s internal debate has followed many of the paths he outlined. There has been a tightening of institutional controls across the financial system, coupled with measures to stabilise local government finances and risks within the banking system. But while market economists have persistently called for some sort of bailout or stimulus, Beijing has preferred to cauterise the wounds and pursue design and structural improvement, implicitly rejecting the view that the current crisis simply reflects cyclical problems.

The core debate, which Lan asserts clearly, is about how China’s markets can be made more flexible and supportive of private activity. And, fundamentally, how the core economic strategy can be shifted away from a heavy reliance on consumer savings conscripted by the state and toward a much higher level of consumption.

While the economic signs remain soft — twenty-one of thirty-two provinces failed to meet GDP goals last year and all have downgraded targets for 2025 — Beijing may be signalling that it’s ready to make deeper reforms. Commentary from a range of senior people, including the central bank governor, suggest consumption-boosting policies are on the agenda. And some interpretations of the most recent politburo plenary and central economic work meetings say local government’s responsibilities must be matched with greater funding and subsidised activity must be strictly controlled.

What we often forget, and Lan makes clear, is that China has a range of basic issues to resolve. It must decide how to resolve the inequities inherent in its size and geography. Urbanisation has been a huge influence in improving living standards, but the household registration system, hukou, continues to penalise mobility. An ageing society demands increasing levels of health services that China’s tax and insurance systems can’t accommodate. And the ambitious innovation and science agenda implies much greater commitment to education spending than is in evidence today. Overall, taxes need to be raised to adequately finance any sensible agenda.

Xi appears to be driven by the singular mission of sustaining the role of the Communist Party. Part of that is expressed in his long-running anti-corruption campaign, which is both popular and effective in tackling a serious threat to party legitimacy. Another part is a tightening of security and suppression of dissent, which may be an attempt to pre-empt the reactions when unviable industry and mirage property investments meet their inevitable fates. Or it may be the mechanism by which the party is sustained should today’s strategy fail.

Lan offers two different pictures of the immediate outlook for China. One is dominated by the baggage of decades of unbalanced investment and spending that has left provinces seriously indebted and a potentially wide range of industry vulnerable to any withdrawal of financial support. The other is of a dynamic, highly competitive and provincially driven system that fosters innovative developments in new energy, high productivity in industry and technological advances. Evidence exists to support both views.

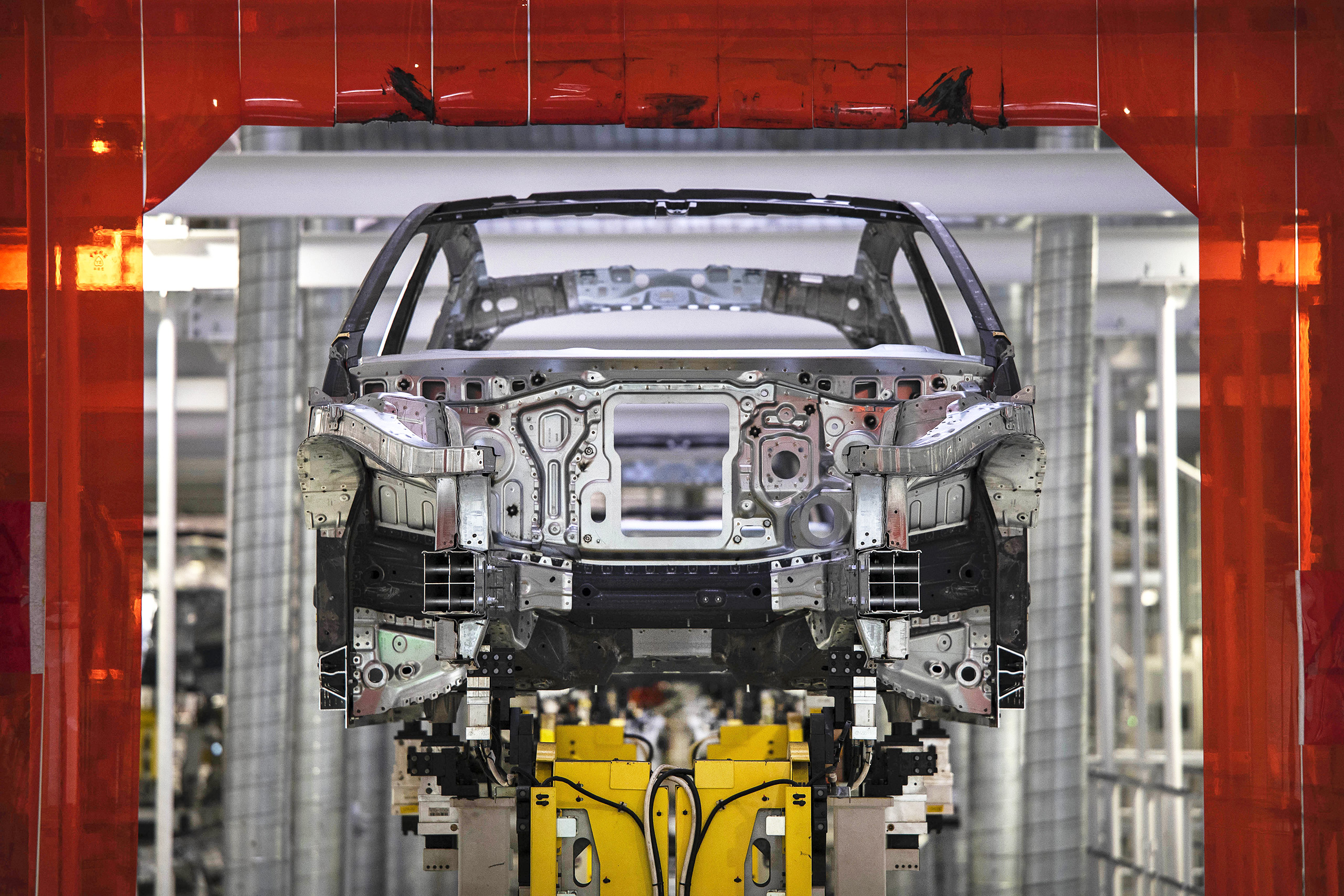

The latter view receives some support from a new strand in China’s policy narrative expressed in the phrase “learn from Hefei.” Exemplary models are typical in party proselytising, but this campaign suggests something new. Hefei, a large provincial city inland from Shanghai, has a reputation for innovation and entrepreneurship: it persuaded the national science and technology university to move from Beijing and fostered successful ventures in semiconductors and, with the high-tech manufacturer NIO, electric vehicles.

But the Hefei message may be about more than innovation itself. Xi’s “modernisation” mantra has attracting a great deal of criticism for its apparent failure to foster the private initiatives that typically deliver China’s success stories. Promoting Hefei means promoting the city’s integration of public and private risk-taking. If Beijing is redesigning the local investment models so familiar to Lan to engage with private initiatives and commercial imperatives, it may be that the DeepSeek example is a forerunner of much more to come.

In an epilogue, Lan reminds us that over forty years China’s GDP grew by 242 times. (Not 242 per cent, but 242 times!) A typical Chinese who earned 20–30 yuan a month now earns 4000–5000 yuan. “People from outside China, no matter how much knowledge and how many theories one has, will not have personally experienced the ups and downs, manias and panics, joys and sorrows of this momentous era.”

Having laid out enough detail to leave an indelible impression of massive challenges, Lan says he is optimistic. Not because of any theory, but out of a personal belief that arises from Chinese history and culture and “an admiration for the hard work and pragmatic attitudes of the Chinese people.” •

How China Works: An Introduction to China’s State-led Economic Development

By Lan Xiaohuan | Palgrave Macmillan | $172 | 366 pages