The edition of Charles King’s Every Valley on the shelves of Australian bookshops — the Bodley Head edition, published in London — has the subtitle, “The Story of Handel’s Messiah.” In the United States, where King is professor of international affairs at Georgetown University in Washington DC, the Doubleday edition carries not so much a subtitle as a spoiler: “The Desperate Lives and Troubled Times that Made Handel’s Messiah.” A little dramatic, perhaps, but accurate enough.

Messiah appeared in 1742 at a moment in British history characterised by political turmoil. In just one century, two kings had been deposed, the first in an act of regicide; a German dynasty had been foisted on the country to preserve Protestant rule while Catholic pretenders were at the gate; the country was forever at war; and, in living memory, there had been a deadly pandemic. So plus ça change, really.

The “desperate lives” in King’s book may seem equally familiar to us: a once-fashionable composer struggling for attention; a famous performer cancelled after a public scandal; a man of little talent using his privileged status to bully and intimidate; London itself, with “suffering and cruelty so fully on display,” not least in the form of its legions of abandoned children.

It was almost chance that led Charles King to wonder about the world that produced this famous work for soloists, chorus and orchestra. He and his wife are charmed by old recordings, and early in 2021 they acquired the shellac discs of the first complete recording of Messiah, conducted by Thomas Beecham in 1927. King’s wife had been seriously ill, Covid-19 had come and stayed, police brutality against African Americans was on display across the United States, and a few blocks from the Kings’ home an armed mob attacked the Capitol with the aim of disrupting the democratic process of government and lynching the vice-president.

“Comfort ye,” sang the tenor Hubert Eisdell at the start of Handel’s oratorio, “comfort ye my people.” These words from the prophet Isaiah, put to music in the middle of the eighteenth century, recorded in the early twentieth and heard in the twenty-first by King and his wife through the surface hiss of an old 78, reduced the listeners to tears.

Messiah was not Handel’s idea. Charles Jennens was an English country gent, an antiquarian with Jacobite sympathies, and he idolised Handel — “the Prodigious,” he called him — to the point of collecting his printed music and binding it in leather. When Jennens died his Handel collection numbered 368 volumes. Like many fans, he also wrote to his hero, going so far as to propose ideas that Handel sometimes took up. One of these was Messiah, to be based on Jennens’s carefully curated selection of scriptural verses, ranging from the Hebrew Bible’s prophecies to the birth, death and resurrection of the New Testament Christ. King calls it “a kind of dramatised philosophy,” yet it was scarcely dramatic at all. There is no action in Messiah.

Even so, the German-born Handel, this man of the theatre whose London fame rested on a string of operatic hits, saw the potential in Jennens’s libretto. By 1741, when no one wanted his operas, religious oratorios were Handel’s attempt to rebuild a career. In August and September of that year, in a little over three weeks, he completed the composition of Messiah in short score and then took himself off to Dublin for a season of concerts.

King doesn’t set out to elucidate Handel’s work — certainly not in any musicological sense; rather, he paints a cast of characters more or less tangential to the work’s creation, and does it with verve. The most tangential is Ayuba Diallo, an educated Muslim man (he spoke six languages) from Bundu in what is now Senegal, who was accidentally rounded up by the Royal African Company in 1731 and packed off to America to work as a slave.

Diallo’s story is both remarkable and salutary. He talked himself free, made it to London where he became a celebrity, had his portrait painted and met the king and queen. In due course he returned to Bundu and commenced work for, yes, the Royal African Company.

Diallo has no direct connection to Handel, but his story serves to remind us that in eighteenth-century London (and many other European capitals) wealth depended, to some extent, on slavery. You didn’t have to be an active participant, as Diallo became. But if you had “means” (to use King’s word) they were probably tainted, and Handel received payments from the Royal Academy of Music and the Crown through annuity accounts held by the Royal African Company.

An altogether more uplifting story is that of Thomas Coram, the retired sea captain whose life’s work culminated in the establishing of London’s Foundling Hospital. A man of almost Dickensian goodness and persistence, he worked for nearly two decades to raise money to get abandoned children off the streets and, at the end, enlisted Handel’s support, mounting annual benefit seasons of Messiah directed by the composer.

Perhaps most touching of the stories King tells is that of the actor and singer Susannah Cibber, sister of the composer Thomas Arne. She married a through-going scoundrel named Theophilus, son of the actor–manager Colley Cibber, whom Pope in his Dunciad called the “Antichrist of wit.” Theophilus, an actor of little talent, a drunk, a bully and constantly in debt, was always on the lookout for ways to make money. He persuaded Susannah to sleep with his friend William Slope in exchange, we presume, for payments.

Whatever Susannah may initially have thought of this arrangement, she quickly decided that Slope was in all ways preferable to her vile husband. When Theophilus discovered they were meeting in secret, he sued the pair and stalked them from dwelling to dwelling. Anyone who thinks social media alone is responsible for the destruction of reputations should read this cautionary tale. The denizens of Grub Street had no need of Facebook. Susannah’s London career was destroyed, and yet, courtesy of Messiah, her story had a happy ending.

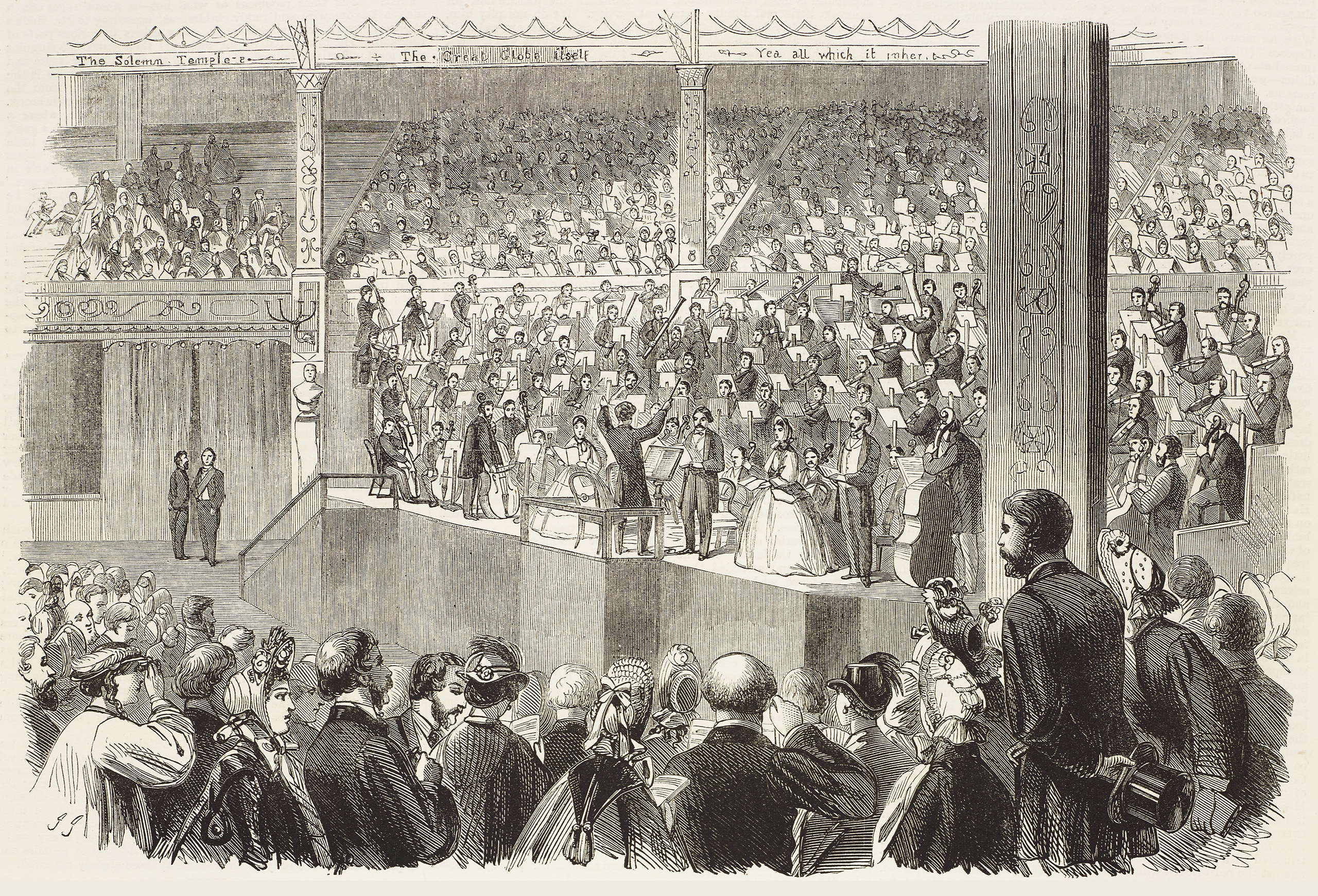

As chance would have it, she and Slope had fled to Dublin around the time Handel arrived in the city, and she had found work there on stage. In April 1742, Handel finally mounted the first performance of Messiah in Neale’s music hall, his forces including two cathedral choirs (one from Johnathan Swift’s St Patrick’s Cathedral, one from Christ Church). An Italian opera singer performed the soprano arias, while Susannah Cibber sang the alto arias.

By all accounts, she never had much of a voice, but what she lacked musically she made up for in theatrical acumen. Here she was, this “fallen woman,” her story known to everyone in the capacity audience, method acting her way through Handel’s aria: “He was despised of men, a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief.” At the finish, Patrick Delaney, chancellor of Christ Church, is said to have shouted: “Woman, for this be all thy sins forgiven!”

“Every valley shall be exalted and every mountain and hill shall be made low,” says Isaiah, the words forming the text of Messiah’s first aria. It was one of Martin Luther King Jr’s favourite Bible verses, one that he quoted in his “I have a dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial; a verse that, for King, embodied the promise of a fairer and more just world.

For Charles King, this is the message of Messiah. Jennens’s libretto, he says, offered “the staggering possibility that the world might turn out all right.” That’s what Handel’s Messiah still offers its listeners and its singers; and it’s what it offered King and his wife in 2021 as they sat with their crackly 78s.

“Time travellers in search of someone else’s memory” is how King describes them at their windup phonograph. But really it’s the music that travels, Jennens and Handel’s great oratorio reaching out across nearly three hundred years to comfort and console. •

• Charles King talks to Andrew Ford about Every Valley on The Music Show.