While it’s generally poor taste to mention an author’s age, it’s uplifting for many reasons to read a highly accomplished biography by a ninety-four-year-old writer dealing with an author who produced her one and only masterpiece in four furious weeks during her late sixties. Australian biographer Brenda Niall’s latest book, Joan Lindsay, is fuelled by her desire to understand how her subject achieved this unusual feat when she wrote the classic Australian novel Picnic at Hanging Rock.

Niall adeptly distils her own biographical quest into a hook for the reader. In her 2005 Seymour Biography Lecture, published last year in Chris Wallace’s collection Telling Lives, she recalls the lack of interest in biography-writing among her fellow literature academics in the first decades of her university career. In the 1950s and 60s, the literary text was everything: “If we had thought [biography] belonged anywhere in a university, we would have consigned it to history.”

As attitudes began to change in the 1980s, Niall had an opportunity to write the biography of Australian novelist Martin Boyd. Gaining access to his diaries, she wasn’t immediately drawn to the “humdrum record” of his later life. But his final entries, as he faced death in a diminished financial and physical state, moved her. She was drawn to the disconnect between the melancholy of the diaries and the joviality of his public persona. “It was from that point,” she writes, “—contemplating the way Boyd faced his death — that I felt I wanted to know the beginnings… I knew there was a story to tell.”

Beyond the initial quest, Niall’s biographies are shaped by the obstacles she encounters. In Boyd’s case, it was the delicate matters of his sexuality and convict ancestry. The latter had caused Boyd’s family to put a stop to an earlier biography by the impeccably credentialled literary journalist Geoffrey Dutton.

Niall puts her relative success with Boyd’s literary executor down to timing, and it’s true that the intervening twelve years had softened attitudes to both homosexuality and convict origins. But, reading Niall’s biographies, it’s easy to see how her sensitive navigation of controversies and uncertainties has made it hard for descendants to reject the lives she has recreated.

After Boyd, Niall went on to write nine more biographies, of which a few are group biographies and the remainder single subjects. Two of them were written in the last decade of her working life and the other eight — including 2020’s group biography Friends and Rivals, on the fresh connections she uncovered between Australian writers Ethel Turner, Barbara Baynton, Nettie Palmer and Henry Handel Richardson, and now Joan Lindsay — in her “retirement.”

Niall’s challenge in writing Lindsay’s biography was neither possessive nephews nor secret lovers. In setting out to solve the mystery of what in the writer’s inner and outer lives led her to produce her “one remarkable novel” at such an age, the clearest problem was a lack of archival material and definitive information about her subject’s motivations. Lindsay was one of those letter burners whose long life gave her plenty of time to curate her archive. And her 1962 memoir Time Without Clocks was more a slice-of-life than a tell-all, which was typical, says Niall, among women of her generation and class who were “schooled in decorum” and shirked from writing or talking about themselves.

Faced with a similar, or even more extreme, dearth of material, some biographers have turned to what’s called speculative biography. An advocate for this approach, and co-editor of the textbook Speculative Biography, Kiera Lindsey pieced together the story of her forebear Mary Ann Gill from scant evidence to write her 2016 biography The Convict’s Daughter. Her more recent Wild Love, about the Sydney-born nineteenth century artist Adelaide Ironside, saw her fill the gaps in a slightly larger, but sometimes untrustworthy, archive by imagining Ironside’s response to documented events.

Other biographies — including Kerrie Davies’s Miles Franklin Undercover, published this month — use wide-ranging archival and printed sources to reconstruct their subject’s world, but Brenda Niall’s Joan Lindsay isn’t one of them.

In writing about Joan Lindsay nee à Beckett Weigell, a cousin of Martin Boyd, Niall uses her knowledge of Melbourne’s wealthy and artistic early-twentieth-century milieu, and builds on it with imagination. But instead of using novelistic techniques, she speculates in a more transparent way.

Niall becomes a character in the narrative, whispering in the reader’s ear: “It may be…,” “It is likely…,” “Perhaps…” Each insight becomes “a trail of breadcrumbs” that helps answer that question of how Joan accrued the qualities and experiences that enabled her to write her most powerful work. Exploring Joan’s privileged background, for example, Niall considers the personal slights that may explain the heightened emotional register of certain characters in Picnic at Hanging Rock.

Born in 1896 in the Melbourne suburb of St Kilda, with a barrister father and a maternal grandfather who was once the governor of Tasmania, Lindsay had grown up in a twenty-four-room house with two Steinway grand pianos. Young women’s freedoms were so severely restricted that many were brought to a point of crisis. Ignored by her parents as the unwanted third daughter rather than the hoped-for son, Joan saw herself as an outsider when she was sent to a local girls’ school at thirteen and tried, “perhaps too hard,” to catch up.

Seeing in Joan’s early history the bullied-to-death character Sara of her novel “may be a stretch too far,” Niall writes. But in Joan’s memoirs she finds traces of the “shame and humiliation” the author amplified in fictional form.

Structural sexism, continually surfacing in the biography as an inhibition on Joan’s capacity to write, eventually forms a theme of her major work. In early adulthood, she didn’t want the usual middle-class girl’s life of meaningless social events while she waited for someone to marry her. But she also felt educationally ill-equipped for an early hope of a career in architecture. Instead, because she “wanted to do something,” she enrolled at the National Gallery of Victoria’s art school.

At art school Joan built the visual sense that would enable her to create the environment of her novel. She was taught by the artist Fred McCubbin, who depicted the ill-ease of settler colonists in a beautiful but hostile landscape. Niall beautifully evokes the ambivalence in the artist’s rendering of the Australian bush in his painting The Lost Child to show how it influenced Lindsay: “The softness of the light, and the touches of pale blue and golden-brown undergrowth, claim and enclose the child. There is no way out; the barrier of saplings makes its final statement in a way that is almost comforting.”

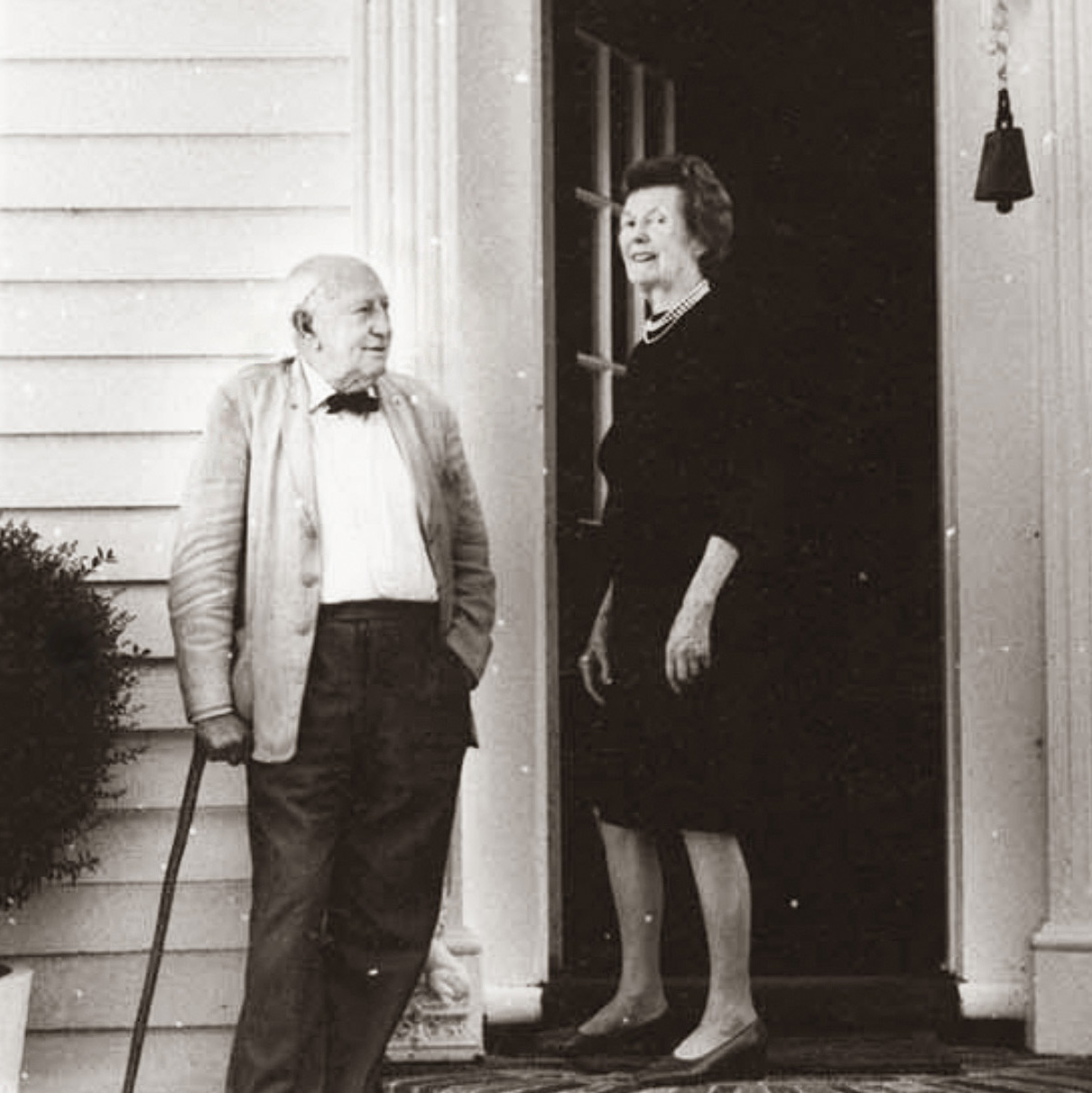

Niall echoes this ambivalence in her portrayal of Joan’s marriage to artist and National Gallery of Victoria director Daryl Lindsay. Perhaps, she ventures, Joan gave up art in favour of writing because Daryl was struggling to prove himself under the shadow of his talented artist brothers Norman and Lionel. He lacked the sure standing to compete with a talented artist wife.

Without any clear evidence about Joan’s feelings about the marriage, Niall breathes life into the silences. She has enough clues to strongly indicate Joan’s unease at her husband’s obsession with ballerinas and his close friendship, and possible romance, with gallery colleague Ursula Hoff. On Hoff, Niall puts it succinctly after comparing the two women’s status in the gallery as employee and wife: “The two women didn’t become friends.”

Niall makes clear that the marriage was a major obstacle in Joan’s creative career, but she doesn’t emphasise victimhood in this case of wifedom. Joan won the battle over where to live — Australia rather than Daryl’s preference for England — and had more opportunity to write than most women of her generation. The decades she spent supporting Daryl’s career rather than fulfilling hers saw her writing art criticism — though barely credited — as well as “playlets” to be performed for Vivien Leigh and Lawrence Olivier, Keith and Elisabeth Murdoch, and other guests at the couple’s rural property. Daryl’s reference to his wife’s “minor talent” as a visual artist in his 1965 memoir may have been a significant catalyst for the anger and determination she needed to write her novel, but he did praise her writing ability.

Even if I wasn’t always convinced by Niall’s suppositions, they are offered with an openness to alternatives. When Joan is seen visiting the set of the Picnic at Hanging Rock film and embracing the actor Anne Lambert, I’m not sure her “tearful reaction” really was a sign that the character in her novel represented the child she was unable to have. But Niall allows space for another interpretation — that perhaps she was overwhelmed at the physical manifestation of her imagination.

Niall is assured in judging her subjects according to the behaviours and ideologies of their time. While she stresses that Lindsay wouldn’t have been aware of the First Nations history of her novel’s setting, she shows that the novelist was at least asking the question, “to whom did the earth belong?” Clearly not to the girls in long white muslin dresses who emerged into the landscape of Lindsay’s tale from their Anglophile institution and were swallowed whole.

Niall’s fellow nonagenarian writer David Malouf told Susan Johnson last year that he has little interest in biography “because what the writer herself or himself has to say in letters and diaries is always more interesting than anything a biographer says about them.” I’d challenge him to read Niall’s Joan Lindsay. As Brenda Niall stresses in Telling Lives, the art of biography involves creating something with “a life of its own.” •

Joan Lindsay: The Hidden Life of the Woman Who Wrote Picnic at Hanging Rock

By Brenda Niall | Text Publishing | $36.99 | 288 pages