Rohan Howitt’s excellent new book, The Southern Frontier: Australia, Antarctica and Empire in the Southern Ocean World, landed in my mailbox on the same day Donald Trump announced sweeping tariffs on imports into the United States. While China, Canada and Mexico were prime among the president’s targets, several unexpected casualties were slated for economic punishment. None seemed more curious than the Heard Island and McDonald Islands territory, whose products now faced a 10 per cent barrier.

To anyone interested in Antarctic history and geopolitics, these islands — especially Heard Island with its massive 2745-metre volcano, Big Ben — are well-known Australian territories. Those keeping up with ocean conservation news would have some idea of the Albanese government’s moves last year to expand the size of the marine protected areas surrounding the islands. But most of us, I hazard to say, have scant knowledge or awareness of these small islands in the Southern Ocean. They are dominated by tempestuous winds, glaciers, penguins and seals and have no permanent human inhabitants. Surely they possess no manufacturing plants to which some rapacious multinational had offshored American jobs?

Most likely, some poorly informed political appointee mistakenly believed that the toothfish caught in these Southern Ocean waters is sold into the United States by companies headquartered on the remote islands. Naturally, the meme factories of the internet (thankfully unhindered by tariffs) went into rapid production. AI-generated images of penguins torching Teslas proliferated, highlighting the absurdity of the announcement.

But is it any more absurd that the Commonwealth of Australia should possess these distant islands as external territories? Heard Island was most likely first discovered by a sealer from the United States in 1853, and American sealers were its most frequent early visitors, although some Australians ventured there too. Britain asserted control in 1910 in legally dubious circumstances and did nothing to occupy the island. When the Chifley government decided to annex Heard Island in 1947 as part of its larger push to occupy the Australian Antarctic Territory, the British government assented despite its legally tenuous title.

For understanding why Australia has territories in Antarctica and the Southern Ocean, Howitt’s book is essential reading. Using a range of public texts — especially newspaper articles — he narrates and analyses the development of Australian ideas and actions in relation to the Antarctic from the late 1830s to the late 1930s. A key year is 1933, for that was when Australia, following exploration and discoveries by Douglas Mawson and other representatives of the British Empire, claimed territorial sovereignty over the Australian Antarctic Territory.

The Southern Frontier carefully considers the ideologies, utterances and contexts of a constellation of political, scientific, commercial and geographical figures. While some have famous names — Mawson, for example, and the great geologist Edgeworth David — the sheer number of less well-known players shows the extent of Antarctic interest in the colonies and, later, the young Federation. For most of the book, this is a bottom-up exercise, not the grand plan of any Australian government.

While Howitt touches only very briefly on Heard Island’s history, he greatly illuminates the larger trajectories and themes of Australia’s preoccupation with and occupation of the Southern Ocean world. This is the first book in generations looking at the development of Australia’s Antarctic obsession in its formative period. Although there is now a rich Antarctic historiography, only R.A. Swan’s Australia in the Antarctic of 1961 has attempted what Howitt does. Swan’s book, like Howitt’s, emerged at an important geopolitical moment: the former, just after the Antarctic Treaty was signed, with a new internationalist era for the continent beckoning; the latter, amid increasing geopolitical tensions and uncertainties.

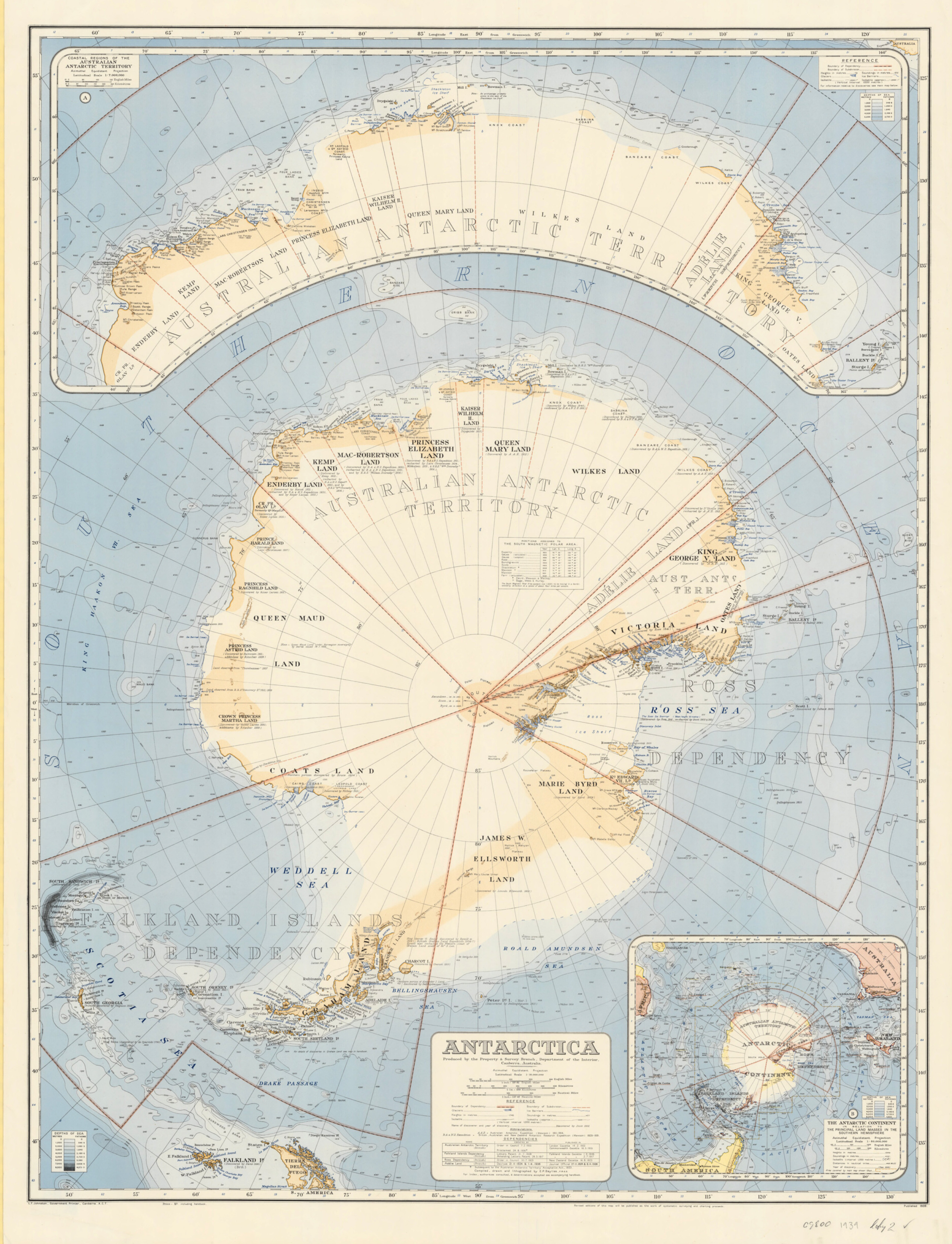

The Southern Frontier offers a big argument: Australians, the product of the United Kingdom’s imperial project, had their own colonial and imperial projects in surrounding seas. As Howitt puts it, “‘Australia’ is radically larger than the familiar, continental map,” for it includes “two continents,” “three oceans and four seas,” and “a sprawling network of island territories stretching from the Antarctic coastline to just shy of the equator.” This makes his book as much an intervention into Australian historiography as a detailed narrative about Antarctica. Howitt suggests a new cartography of Australian historiography, recognising “a vast Australian archipelago… stretching from Christmas Island, New Guinea and Nauru in the north to Antarctica itself in the south, and from Norfolk and Macquarie islands in the east to Enderby Land and the Heard and McDonald islands in the west.”

Australians have rather forgotten that this country had colonial possessions and has naturalised those external territories it still possesses as merely ordinary parts of the country. While earlier generations were more aware of this — especially in the period when Papua New Guinea was under Australian rule — both public awareness and historiographic appreciation has rather diminished. The language of “settler colonialism” has increasingly suffused public discourse and historiography, but some might imagine that it ends at the Australian continent’s coast. As Howitt strongly argues, “What becomes clear when Australian history is viewed from the south is that the expansion of settler Australia was a long-term, outward-looking, extra-continental project as much as it was an internal one.”

The Southern Frontier begins in the years between 1839 and 1841 with the visits of the great navigators who were, among other things, searching for the south magnetic pole. The colonial denizens of Hobart and Sydney were electrified by their encounters with the American Charles Wilkes, the Frenchman Dumont d’Urville and the Briton James Clark Ross and their crews before and after their forays into the icy south, sharing new knowledge and feeding Australia’s geographical imagination. While others have interpreted the following three or four decades as a period of low interest, Howitt skilfully shows the small eruptions of awareness and discussions in the colonies, whether in response to new whaling opportunities or among the growing scientific communities of the colonies, which searched for new knowledge that might legitimise their colonial intellectual world in the eyes of metropolitan Europe.

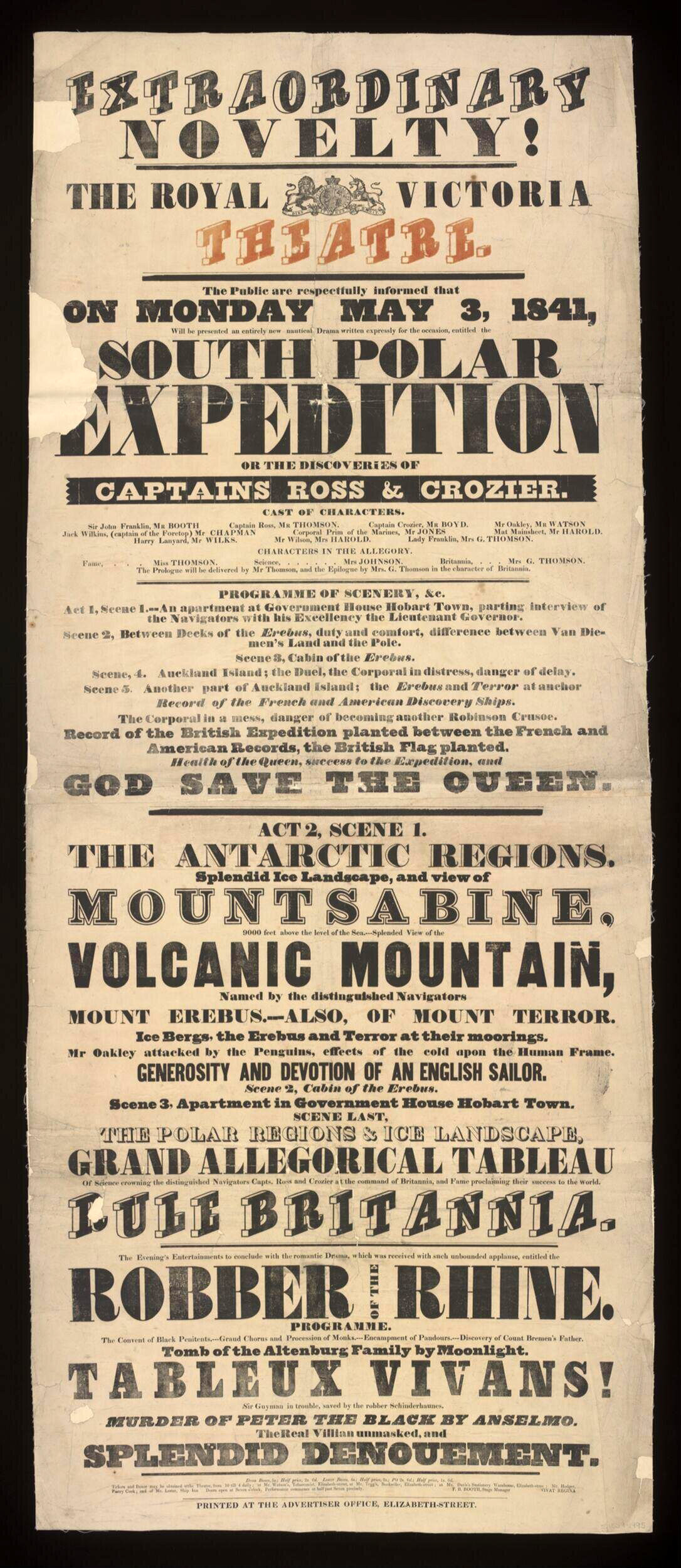

During James Clark Ross’ second stay in Hobart in 1841, the Royal Victoria Theatre staged a “new nautical drama,” South Polar Expedition. Victoria and Albert Museum

A more active Australian interest in the Antarctic resumed in the 1880s. In Melbourne, the new Antarctic Exploration Committee gathered prominent citizens and members of the geographical society, holding large public meetings in the hope of generating interest, and therefore funds, to send an Australian expedition. Had it succeeded, it would have been the first major expedition to the icy continent, yet its ambitions were thwarted by an inability to raise sufficient money because, Howitt suggests, of a confusion of scientific and commercial aims. What Howitt illuminates in this story, however, is the language of imperialism evident in calls not only for an Australian “empire of the southern seas” but also for a “Monroe Doctrine” for Australia. This period saw the growth of not only of federalism but also, simultaneously and intimately connected with it, of Australian imperialism.

It was in the 1890s that the first Australians visited Antarctica. The Norwegian-born duo Henrik Bull and Carsten Borchgrevink, who’d both settled in the Australian colonies in the 1880s, were part of the first party to step onto Antarctica in 1895. Howitt’s narrative emphasises how the usual description of these men as Norwegians overshadows the fact that their Antarctic trajectories were shaped in Australia.

And yet, in the first years of the Federation — the very moment when Australia seemed finally to have begun to physically connect with the continent of ice — there came an intriguing and ironic lull in activity and interest. Although an early public discussion in the young Federation was the question of annexing the Kerguelen islands, a French possession in the Southern Ocean, Australian activities took a back seat to the more prominent British undertakings of the Royal Geographical Society. Robert Scott’s Discovery Expedition (1901–04) claimed the attention and resources of the British world, although Howitt shows how Australians claimed this imperial effort.

But Australians weren’t only supportive of Scott; they were, in Howitt’s original observations, highly supportive of all exploration of Antarctica, enthusiastically welcoming the Japanese expedition of Nobu Shirase and the Norwegian expedition of Roald Amundsen — the latter of which had infamously, at least to British eyes, stolen the achievement of the South Pole from Scott in 1911.

In the final parts of the book, Howitt brings us to the fruition of all the communal interest in a south polar empire. Between 1929 and 1931, under Douglas Mawson, the British Australian New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition was commissioned by the Commonwealth government to discover and claim land. The ungainly name obscured the essential Australianness of the endeavour. Mawson’s proclamations along the coast formed the basis of what would become the Australian Antarctic Territory in 1933.

Across the century Howitt observes three major shifts in discourse about the Australian relationship with the region to its south. The first was the development of a language of “interests.” There were commercial opportunities, principally the exploitation of various animal populations, which Australians had proximity to and could enrich themselves on. The second shift, from around the 1880s, was to insist on Australia’s “rights.” This was an intensification of interests, for it implied that others could not and should not have interests overlapping with Australia’s.

The third shift in the 1910s and 1920s was Australia’s assumption of “responsibilities” for Antarctica. Here Howitt has an incisive take on events. In his telling, these responsibilities were closely tied to explorers in peril and the string of rescues that Australia felt entangled in. The death of Scott in 1912, the challenges of Shackleton’s Trans-Antarctic Expedition in 1916, even the apparent loss of the blundering American aviator Lincoln Ellsworth in 1935 — all generated sentiments of rescue, safety and, eventually, responsibility over this region.

“Responsibilities” remains a potent part of international Antarctic discourse, embodied in various statements and assertions of the Antarctic Treaty parties since the 1970s. Howitt’s careful and critical reading of Australian public discourse of the early twentieth century offers an intriguing precedent to the later uses of the term.

A turning point in the history of Antarctic cartography, this map, published by the Commonwealth government in 1939, attested to the sense of responsibility Australia had for knowing and governing the icy south. National Library of Australia

While Howitt generally frames his book in terms of ideas and ideologies, it is also highly evocative of the material presence of Antarctica in Australia. Antarctica was more than an abstract realm for Australians; it was a world brought to them physically, most often embodied in explorers. Howitt gives a vibrant sense of Hobartians and Sydneysiders jostling to meet with great Antarctic visitors, from Wilkes, Ross and d’Urville to Ernest Shackleton, the Japanese Nobu Shirase and Australia’s own Edgeworth David and Douglas Mawson. He also retrieves fascinating and rather forgotten remembrances of these visits: people who had met and worked with Ross during his Hobart visit remained active for the Antarctic cause in the 1880s and 1890s.

Australians also grabbed souvenirs of Antarctica from the navigators and explorers. When Shackleton’s Nimrod sailed into Sydney in April 1909, one of the expedition crew noted that “every scrap of spare wood and rope was disposed of; every scrap of penguin skin or sealskin; every penguin and skua egg; every small piece of erratic rock, found their way into the pockets of enthusiastic sightseers.” Even puppies born in Antarctica were given to prominent Australian supporters. These Antarctic fragments must surely still be sitting on family mantlepieces or (perhaps more likely) languishing forgotten in cupboards around the country.

Southern Frontier is a compelling book. Some of the personalities, events and developments will be known to those with any interest in Antarctica or the history of exploration. Yet Howitt puts them into fresh perspective, carefully drawing out a world of ideas and ideologies, forgotten and marginal figures, and making new connections between events previously viewed in isolation.

While Australia’s contemporary approach to Antarctica seems benevolent and positive — see the Australian government’s aim that Antarctica be “valued, protected and understood” — Howitt’s book might make many see it in a different light. In 1936 Melbourne’s Argus newspaper asserted that Australia had a “mandate of empire to supervise and explore the land and water stretching away to the south.” How much of that attitude do we retain today? •

The Southern Frontier: Australia, Antarctica and Empire in the Southern Ocean World 1815-1947

By Rohan Howitt | Melbourne University Press | $39.99 | 288 pages