The idea that the world needs more babies is fast becoming an orthodoxy. Unless something changes soon, say the pro-natalists, human populations both national and global will decline rapidly, with many negative consequences. On any plausible assumptions about fertility, however, this is simply not true.

There’s no need for me to do the sums here. For many decades the Population Division of the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs has been producing population projections for the world, and for individual countries, under a variety of scenarios. One finding is unambiguous. Short of a drastic decline in fertility from already historically low rates, there will be more people on Earth at the end of this century than there were at the beginning.

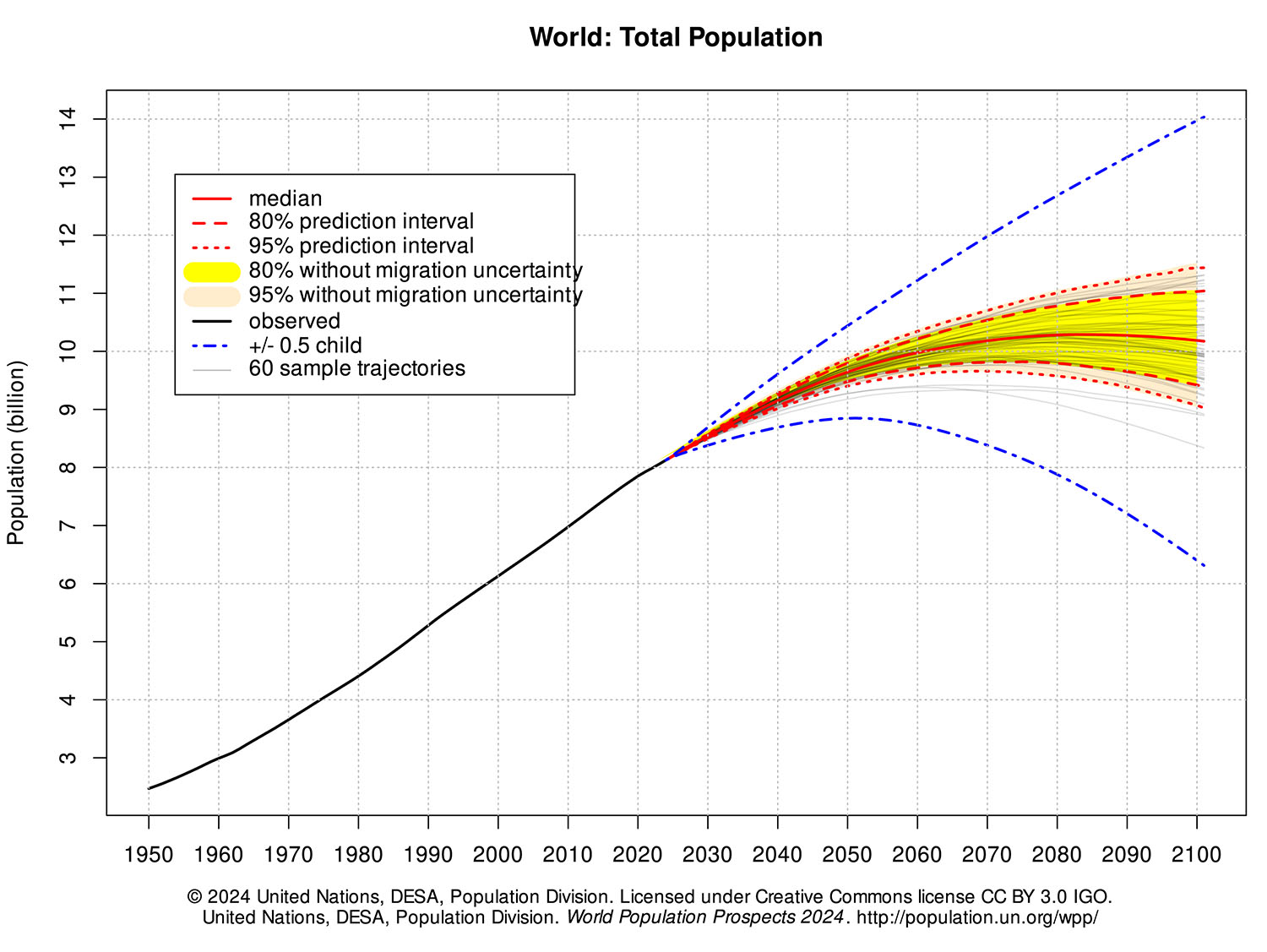

In the chart below, the range of projections considered plausible fall within the shaded area. Each projection in that range shows population increasing for several decades to come, and remaining higher than at present at the end of the century. The reason is simple: global fertility is currently close to replacement level (one surviving daughter per woman) but past growth means that a large proportion of the population is in, or approaching, child-bearing years. It’s only when this group ages out that the effects of declining fertility, assumed in the lower projections, will start to dominate.

What about the blue dotted lines? These scenarios assume drastic reductions in fertility. For the lowest, that would mean the entire world becoming like South Korea, where the combination of high employment rates for women and pre-modern male attitudes to gender roles has produced reproduction rates below 0.5.

But even in that extreme case world population in 2100 only falls to six billion, the same as in 2000. I was around at the time, and it didn’t feel as if there were too few people about.

One reason these predictions have only a limited range of variation is that most of the growth in population is already baked in. There are two billion or so children under fourteen in the world, and most of them will be around in 2100, as will their soon-to-be-born siblings.

What about the need for workers? One unsatisfactory feature of long-running projections like this is the use of outdated statistical concepts such as the “old-age dependency ratio” — the ratio of people in the fifteen-to-sixty-four age group to those they are assumed to be supporting in old age. In every way, that ratio reflects the social and economic conditions that prevailed in the 1950s. The elements that made it up include:

• the old age pension, typically available at age sixty-five

• the “male breadwinner” model of the labour market

• the exclusion of married women from most forms of paid employment

• compulsory schooling with a leaving age of fifteen

• the “nuclear family,” including a couple and their children but excluding aged parents.

This setup defined a standard life course — or rather two, one for each gender. Young men left school at fifteen and worked until they reached pension age. Their earnings were expected to support a family at an acceptable standard — from the “frugal comfort” assumed in the Harvester wage decision of 1907 to the unaccustomed affluence of the 1950s, but still far short of what is expected today. Young women also left school and entered the workforce at fifteen, but most of them soon married (often already pregnant) and became “housewives,” a full-time job once children arrived.

Old people lived on the pension as long as they were in reasonable health. With good luck they died in their own beds or after a brief stay in hospital. With bad luck, they spent their final year or two in a nursing home. On the other hand, children were cared for at home (apart from attending crowded and poorly funded schools) at the expense of their parents. In these circumstances, the old-age dependency ratio was of keen importance to public finance.

The concept made sense fifty years ago, when the fifteen-to-sixty-four age range represented the period between leaving school and retiring in most industrial societies. But these days (and it will be even more so in 2100) education continues well past twenty and retirement is often deferred to seventy or beyond. The age group twenty-five to sixty-nine is going to remain more or less stable in absolute numbers, declining only marginally relative to the growing population

Population projections for individual countries depend largely on what happens to migration. In the absence of stringent restrictions, the flow of migrants from poorer to richer countries will largely offset differences in fertility, meaning that the trajectory for individual countries will look similar to the world’s.

Of course, if you combine low fertility and an already-old population with hostility to immigrants and you can’t stop your own young people from seeking a better life abroad, you end up with a sharply declining population, as in South Korea and Hungary. But it’s much easier to let more migrants in (there are plenty of young adults, many of them well-educated, knocking at the door) than to persuade people to have more babies.

Conversely, countries like Australia with high immigration and reproduction rates close to 1.0 can expect a steadily growing population. Even with low-end expectations about migration and fertility, our population is almost certain to grow over the course of the twenty-first century.

Not only that, but because migrants are mostly young adults, Australia can maintain a positive net natural increase (an excess of births over deaths) even though the average woman has less than two children.

These projections are easily accessible, and anyone with a spreadsheet and a bit of time can reproduce them. Yet in the stream of pro-natalist articles in both traditional and new media the evidence is never mentioned. It’s worth asking why. In part, no doubt, it reflects conscious or subconscious racism. The concern is not that a given country’s population will fall but that immigration will change the ethnic mix.

But there is, I think, something more fundamental. People have an image (not always realistic) of how families have looked in the past and see a reduction in the number of children as a sign of decay and enfeeblement. This isn’t new. My demographer mother, Pat Quiggin, wrote her master’s thesis, “No Rising Generation,” on the panic about declining fertility in the early twentieth century.

In retrospect, the 1960s, when concern about the “population explosion” erupted, were the exception rather than a new norm. With the baby boom just ending in rich countries and births massively exceeding deaths in poor countries, the idea that we would be worried about a shortage of births seemed far-fetched. But even though the number of births is still close to its all-time peak (reached around 2013), this reversal has indeed taken place. For those still convinced that the planet cannot indefinitely support so many humans as it does, the only comfort is that there is little pro-natalists can actually do to push people into having more children. •