In his new collection of eight wide-ranging essays, the distinguished photographer Michael Collins makes a plea for the art of close observation. The viewer’s role is to look, not merely to glance and then move on, forever under pressure to get to the next image. “Photography’s ubiquity is its nemesis,” he laments, because ubiquity begets scrolling, and scrolling is the enemy of reflection.

This contrast between the rewards of attention to the single image and the reality of photographic abundance forms the thread that runs through Blind Corners: Essays on Photography. That doesn’t mean every image merits the kind of close attention Collins advocates. Most photography, he says, by which he means most photography today, “is the antithesis of photography itself.” It grows “louder and dumber.” It shouts without really saying anything.

Collins favours the photograph that has something to say, that doesn’t shout but leaves us, as viewers, to detect the sound behind the silence. But he is less clear about how we will know when we come across such an image, other than that there is a magic to it. On the other hand, he is very good on the magic part of the equation, on what happens when we set off on a quest — an ultimately hopeless quest — to know and understand the world a singular image represents.

The magic invites us in and leads us to wonder and to speculate. In the first essay of the collection, Collins looks very carefully indeed at an image of Coronation Day, Tenby, 1953. His eye is first drawn to it when he spots a photocopy pinned to the wall in a photography shop. The picture was taken decades before by the owner, Graham Hughes, and shows a group of a hundred or so people posed on a hillside, brought together to create a marker of a day of celebration and commemoration.

Hughes is unable to locate a print of the picture, but after rummaging around in drawers he does recover the glass negative. Collins is charmed by the physicality of it. There is a long scratch on the negative, and a chip in the emulsion, but these too are part of its history, and he recognises that, blemishes notwithstanding, it will “yield a superb print.”

Wonder turning to interrogation: Graham Hughes’s Coronation Day, Tenby, 1953 (above and, magnified by Michael Collins, below). © Graham Hughes

By means of a series of increasing magnifications, Collins deploys today’s technology to reveal a level of detail in Coronation Day that an original, physical print would keep hidden. The result is a sophisticated exploration of what is gained and what is lost by this process of magnification, and at what point “wonder” becomes “interrogation.” Does looking too closely jeopardise the magic?

Magnification, courtesy of technologies developed long after the photograph was taken, allows the viewer to zero in on individuals and to speculate on individual lives. We must base that speculation on the instant recorded by the image. “A photograph does not acknowledge what preceded or followed the exposure.” It does, however, invite us to imagine the before and after of what we see in front of us.

“Photography’s gift comes with despair,” says Collins — despair over what has not been captured by the camera, of what is outside the frame, of what happened just before or just after, of what that expression really means. Is it anger, for example, or indigestion?

This impulse to imagine context, which so fascinates Collins, is doubtless what drives the current fashion for animating photographs, turning them into short films or gif like loops. A man in a top hat suddenly takes the hat off, puts it on, doffs it repeatedly. His eyes move, his expression changes, and yet he does not come to life. Instead, the magic of the still image evaporates, and we are left feeling somehow disappointed.

The stillness provides the magic. Our need to know, hopeless though it may ultimately be, is what really keeps us looking, and what really animates the image. A photograph, like a biography, can never tell us enough. We always want to know more. As Collins demonstrates by his detailed speculations on the inhabitants of Coronation Day, the fact that the people in the picture are motionless, silent and monochrome encourages us to think we are tantalisingly within reach of knowing them.

For Collins, a photograph’s power lies in its very singularity. This is not a fashionable view. We are much more attuned today to look at photographs in relation to one another, not just on gallery walls but in digital archives and curated collections. This tendency to bundle photographs together, with the idea that each image has the power to illuminate the others, is doubtless traceable, in part at least, to the phenomenon of over-abundance and the question of what to do with all these photos. But clearly there is more to it than that.

The photographer Joel Meyerowitz, in a recent project undertaken in collaboration with the platform Fellowship (“dedicated to supporting… artists who explore the boundaries of art using innovative technologies”), reflects on the differing impacts of the singular image and the sequence. “Besides delighting in the purity of the single image,” he says, “photographs can also act like an alphabet of meanings when seen in relationships with other photographs.”

Meyerowitz’s project, entitled Sequels, aims to reanimate his sixty-year archive using blockchain technology to “play with how images interconnect,” but also to invite viewers and collectors to assemble their own sequences of Meyerowitz images. By building their own collections, viewers can create new and unexpected — and to some extent, at least, personalised — meanings.

Collins is not so sure about the power of sequencing. He thinks it can muddy the waters. “Photography is a prisoner of seriality,” he writes. True, photographs can inform one another, he goes on to acknowledge. Seen together, they can bring out “motifs and meanings that might otherwise be more mute.” But this reads more as a concession than a robust endorsement. We don’t feel that his heart is in it. To get the most out of a photograph, he concludes, we must focus as viewers on its “inimitable uniqueness.”

Both Meyerowitz and Collins, in their differing ways, highlight the role of the viewer in extracting meaning from an image, the viewer acting as a co-creator. For Meyerowitz, in line with the times, this participative role is enacted through the process of assembly and curation, the arrangement of images to enhance meaning. For Collins, by contrast, the essential relationship, and arising out of it the construction of meaning, is strictly one to one — between the single image and the viewer.

In the essay “Personal Picture Show,” which acts as a kind of companion piece to Coronation Day, Tenby, Collins turns his attention from group to individual portraiture. In doing so, he reserves his highest regard for those photographers who capture the humanity of the subject or, put another way, offer the viewer a pathway to that humanity.

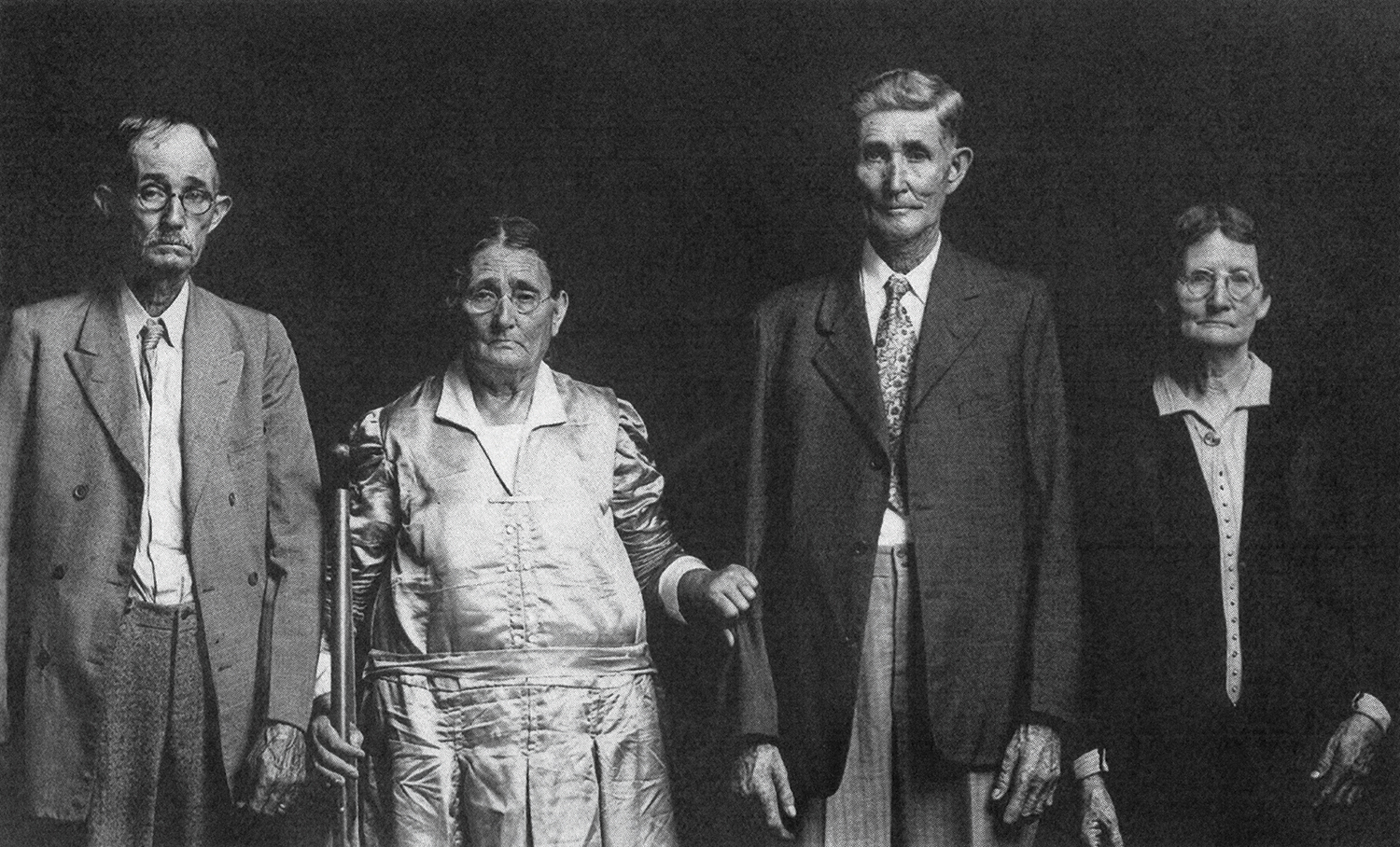

The camera acts as a physical barrier — Collins calls it a “shield” at one point — between photographer and subject, and while some photographers can sidestep or transcend that barrier, others exploit it. For Collins, the portraits made by celebrated mid-century photographers such as Mike Disfarmer and Diane Arbus effectively embalm their subjects, treating them as victims of the camera rather than partners with it. They are not only subjects, but subjected too.

“Like ghosts”: a Mike Disfarmer group portrait from c. 1930.

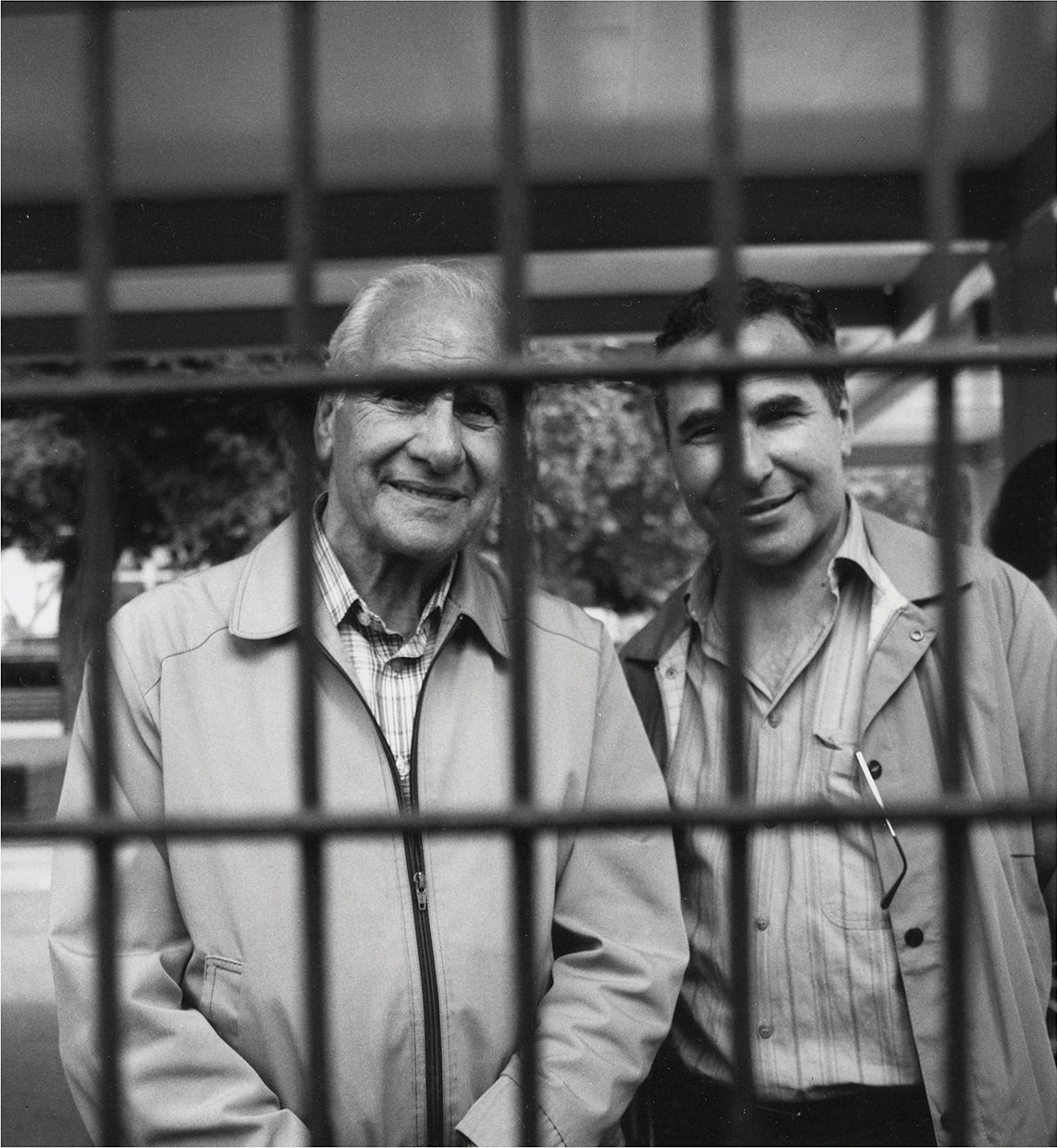

In another of the essays in the collection, “A Big Hairy Hand,” Collins gives a wry account of a newspaper stunt at London Zoo involving a camera and a gorilla, Salome, in which the shutter button, disguised in a log and well separated from the camera itself, is smeared with banana to encourage the giant ape to poke it with a stick. Special praise is reserved for a man and his adult son who, safe on the other side of the bars, pose willingly and patiently, happy to help in ensuring that the animal gets the shot.

Unlike the man and his son who, in strictly metaphorical terms, meet the gorilla more than halfway, Collins sees Disfarmer’s subjects as being altogether without autonomy. They submit to instructions, and in so doing “appear to face us from the netherworld,” rather than from life. Similarly, he regards Arbus’s “fossilised” subjects as serving a “cynically malign melodrama” in which they play their assigned parts.

The collaborators: Salome the gorilla’s portrait of two men.

Disfarmer’s studio clients recall him as an intimidating presence. He was scary, remembered one man who was photographed by him as a child. His subjects obeyed him without question, standing as and where they were told. “Some believe,” says Collins, clearly not believing it, “that Disfarmer’s intimidatory atmosphere was penetrating.” The reason that the gorilla’s photograph of the man and his son turned out so well, we infer, is that his subjects were not scared of him.

“All too often knowingness,” Collins comments, “is blindness.” He is much more drawn to photographers who can, by means of a kind of innocence, succeed in suggesting a life beyond the frame. As he remarks in passing of the greatest of all portrait photographers, August Sander, such photographers treat their subjects as “equals.” In contrast to Disfarmer’s “gothic agenda” or Arbus’s forensic approach, we are led towards someone much lesser known yet much more successful in the author’s estimation in nailing the essence of portraiture.

John Alinder, a near contemporary of Disfarmer’s, devoted much of his time to photographing fellow members of his small community in rural Sweden in the early part of the twentieth century. His life’s work, represented by 8421 glass negatives, sat unseen in a library basement until it was rediscovered and resurrected to form the basis of an exhibition, held in Landskrona in 2021.

Alinder’s wonderful portraits of his fellow citizens are not, it is generally acknowledged, particularly sophisticated in technical terms. A blur here, a camera tilt there. Yet what inarguably shines through is the vitality of the subjects, the sense each portrait conveys of a full biography behind the face and the posture, invisible and unknowable to us yet substantive all the same. Collins attributes this quality to the sympathy the photographer has for the subject. (He says of another photographer whose work he much admires, the Malian Seydou Keïta, that the “heart of his portraits is empathy.”)

Collins acknowledges the memorialising, “melancholic” effect of photography. “What we can see in the instant of exposure has inexorably passed away.” But a memorial can also be an expression of optimism, or at the very least an expression of confidence that there will be a future beyond the moment of the image. One of the many things he admires about Seydou Keïta, for instance, is the way he “posed his clients so that they were facing diagonally out of the picture…, their faraway look uninhibited by the lens.”

Collins gravitates to those images, whether of people or landscapes, that seem to free their subjects rather than to pin them down. Of his own practice, he writes of returning repeatedly to photograph the bare landscape of the Hoo Peninsula in Kent, a subject of which he never tires. The attraction lies in the way that these landscapes “face ahead to open water, where the river meets the sky,” suggesting a counterweight to photography’s essential retrospectivity.

He makes a similar point in a brief but moving meditation on his favourite photograph, of a ship lying aground and abandoned at Brightstone Bay on the Isle of Wight. The subject of the image has reached the end of its journey, seeming to rule out the future. But in a highly magnified print of the original contact, Collins can just spot, in the top left-hand corner, “a seagull with outstretched wings.”

The Kingsbridge, 1955, photographer unknown.

Collins flirts here with sentimentality and, as he does elsewhere, with overstatement, something he does most clearly when making a case for the necessity, where portraits are concerned, of a prior relationship between subject and photographer. “The most sensitive portraiture is generally to be found in the family album,” he maintains. In other words, when photographer and subject are known to one another.

Not only that, but “it is a delusion to imagine that a photographer can make a genuinely revealing portrait of a complete stranger.” Taken at face value, so to speak, this seems unlikely, if not simply untrue. Whether overstated or not, however, the central point remains. The photographs that speak to us most effectively and most directly are the ones that assure us of a sympathetic connection between photographer and subject.

In his introduction to Blind Corners, the novelist Will Self points to its pervasively elegiac quality. This is partly because loss and regret are embedded in the material, in images of the irretrievable past. As Collins puts it in his near to final paragraph, “photography is inherently melancholic because of our innate sense that what we can see in the instant of exposure has inexorably passed away.”

But that is not the only reason. What adds to this elegiac quality is the fact that the kind of photography that Collins responds to with such energy and love is itself retreating into the past. Photographs that have their roots in things that happened, the kind that we will increasingly see as traditional photographs, are now the raw material for generative models, fuel for the post photographic world.

This new kind of machine-driven, AI-enabled photography means a much more tangled relationship with the reality of historical events, one which is already giving rise to its own, very different brand of melancholy. •

Blind Corners: Essays on Photography

By Michael Collins | Notting Hill | $34.95 | 192 pages