FOR ONE Australian voter, 7 September 2013 was a very busy day. While most of us were savouring our election day sausages in the early spring sunshine, someone was practising William Hale Thompson’s famous admonition to “vote early and vote often.”

Reviewing its records from the big day, the Australian Electoral Commission, or AEC, discovered one person had voted fifteen times, scattering ballots across their electorate like confetti at a wedding. This devotee of democracy wasn’t alone, either; the commission has confirmed it is investigating almost 2000 cases of multiple voting in the 2013 poll.

In ordinary times, the fact that 0.013 per cent of voters got a bit over-enthusiastic at the ballot box would not excite much concern. But unfortunately for the AEC, these are not ordinary times.

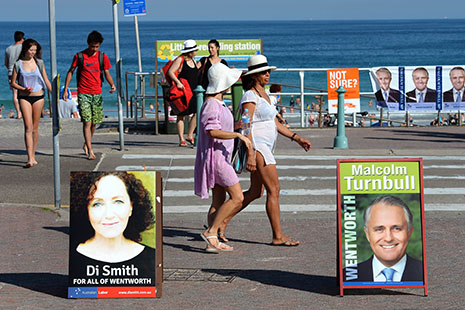

The loss of more than 1300 ballots in the Western Australian Senate count has already put our national electoral system in the spotlight, and a growing chorus of Coalition voices is calling for a major overhaul. Even before this latest revelation, Malcolm Turnbull was pushing for new processes to clamp down on what he called “improper voting.” Within days of the new government taking the reins, both special minister of state Michael Ronaldson and Liberal federal director Brian Loughnane had singled out stricter voter identification rules as a priority reform for future elections.

If the government goes down this path, it will surely have the support of parliament’s newest powerbroker, Clive Palmer, who has complained that the current laws allow Australians to “vote ten, twenty, thirty times if you like.” Holding court with reporters recently, Palmer mocked the supposed insecurity of Australia’s voting system, saying, “to board a flight you need ID, but not to exercise your democratic rights.”

These proponents of voter ID make it sound as though this is a quick and easy fix for a gaping security flaw: a no-brainer reform that will bring voting into line with banking or flying to Bali. But as with so many aspects of public administration, the reality is much more complicated than that.

AUSTRALIA isn’t alone in allowing voters to cast their ballots without showing ID – the United Kingdom, New Zealand and Denmark are among a range of countries with similarly loose rules. In recent decades, however, the international trend has been towards tighter requirements, particularly in the United States, where voter ID has become a topic of heated political debate.

In 2002, George W. Bush signed into law an act requiring new voters to verify their identities when casting a ballot for the first time. That act opened the gates for a flood of new state-based voting laws, and some thirty-four states have now passed laws imposing ID requirements on all voters.

These US state laws differ in whether they require photo or non-photo ID, and how strictly they are enforced by officials at booths. But there is a growing body of evidence showing that, overall, the tighter ID rules are acting to discourage and disenfranchise some voters. These effects are being seen most strongly among young, old, ethnic and poor voters, furthering the marginalisation of these groups.

Dorothy Cooper’s now-famous story highlights why this is the case. In 2011, the ninety-six-year-old Tennessee woman attempted to apply for a state-issued photo ID so that she could vote in the following year’s presidential election. Being too old to drive and lacking any other form of photo ID, Cooper tried to use a collection of other documents to verify her identity. But she hit a wall of bureaucracy because the name on her birth certificate didn’t match the married name listed on her lease and electricity bills, and she was unable to find a copy of her marriage certificate to confirm she was the same person. Local county office staff informed the frail pensioner that they could not verify her identity using those documents, and refused to issue her with a new photo ID. It took a state MP intervening in Mrs Cooper’s case (as well as nationwide media publicity) before she was finally issued with the necessary identification to vote.

Dorothy Cooper’s predicament is not uncommon in America. A 2006 survey from the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University estimated that 11 per cent of eligible American voters lack access to photo ID, with this figure rising to 18 per cent for those aged over sixty-five and 25 per cent for African-American voters. Since the passage of tighter voter ID laws, these citizens must struggle through the bureaucratic mire experienced by Cooper, and often pay expensive fees for the privilege. If they don’t or they can’t, then they are simply turned away on polling day – denied their democratic right to vote.

Of course, under Australia’s compulsory-voting laws, election officials won’t have the option simply to turn away voters who are unable to provide the right ID. That’s probably why the Queensland government took a slightly different tack when it announced Australia’s first voter ID laws late last year.

Introducing the new rules, Queensland attorney-general Jarrod Blijie declared: “Maintaining the integrity of our electoral system is vital, so proof of identity will be required on polling days to prevent voter impersonation.” (This, despite the government’s own electoral reform discussion paper noting that “there is no specific evidence of electoral fraud in this area.”)

At future state elections, Queenslanders will have to verify their identity before voting, but they’ll be able to use a range of documents to do so. These include photographic forms of ID such as a driver’s licence or passport, as well as non-photographic forms including utility bills and leases, Medicare cards and state concession cards. This flexibility greatly reduces the risk that those without photo ID will be disenfranchised. But it also raises questions about how much non-photo forms of identification can actually do to prevent voter fraud.

When voicing his concerns about the security of the current federal system, Malcolm Turnbull told the ABC that “there are a large number of people who vote fraudulently in the sense that they go to the polling place and say they are someone else. Now I think that most of them are doing so honestly – they are doing so on behalf of a friend who is away or who is sick… [but] I think we underestimate the extent to which there is improper voting.” Taking Turnbull’s proposition at face value, how will requiring voters to show a utility notice or Medicare card prevent one person impersonating another? If someone has the forethought to send another voter in his or her place, how hard would it be to also hand over an old electricity bill?

Jarrod Bleijie was right to set his state’s ID standards so low; imagine the Supreme Court showdown if a Queenslander who was legally required to vote ended up being blocked from doing so because he or she couldn’t show the right kind of ID. But the flipside of this flexibility is that the rules are next to useless for preventing one voter from impersonating another – as long as he or she is of the same gender and from roughly the same ethnic or cultural background.

And what about Clive Palmer’s worry about people voting ten times or more? Under Australia’s paper-based system there is nothing to stop someone with any kind of ID voting at multiple booths, because electoral officials have no way of cross-checking their records until after the polls have closed. After each federal election AEC staff use computer scanners to turn the marked voter lists from each booth into a consolidated catalogue of everyone who voted there. Those individual booth lists are then compared to see if any names pop up more than once; that’s how the commission discovered those 2000-odd people who apparently voted multiple times in 2013. Asking voters to show ID might well discourage over-enthusiastic electors, but it cannot prevent anyone from voting more than once unless individual polling places are able to communicate with each other in real time about who has already voted throughout the day – something that is not possible under the current, paper-based system.

At the 2013 election the AEC trialled electronic voter lists at some booths around Australia. These have the capacity to operate from a shared, centralised copy of the electoral roll, and therefore provide up-to-date accounting of who has voted throughout the day. We’re yet to hear how that trial went, but unless these electronic lists are issued to all booths for future elections, it’s hard to see how voter ID laws like Queensland’s would do much at all to prevent the kind of fraud Clive Palmer frets about. On the other hand, if e-lists were installed at every booth, it wouldn’t be necessary to ID voters to stop them voting more than once, because the system itself would do so.

This is the central logic that Australian proponents of voter ID do not appear to have grasped. Implemented as a standalone reform, it will not address the real feature of our system that facilitates multiple voting. But if and when that feature is addressed by the introduction of new technology, the major rationale for voter ID simply vanishes. What’s more, Australia’s compulsory voting laws add a layer of complexity which has so far gone entirely unacknowledged by any public advocate of ID reforms.

ON THE other side of the world, voters in dozens of European countries would no doubt view this discussion about voter ID with mild mystification. In most of the major European Union nations (and many of the minor ones) citizens are legally required to carry a state-issued photo ID card with them at all times. These cards – which the government automatically issues and pays for – carry personal and residential details. They are used for a range of every-day tasks such as banking and travelling between regions or EU countries, as well as for verifying identity when voting in state and national elections.

Increasingly, these cards are being embedded with microchips to store an expanded range of information such as concession and healthcare records. Many also feature barcodes or similar machine-readable components which allow for quick registration and verification of identity – such as when turning out to vote. The fact that citizens are legally required to carry this ID means that in places like Italy, Germany and Spain, identifying yourself is an uncontroversial step in the voting process.

These European ID systems vary in their technology, and therefore also in the extent to which they address concerns about voter fraud. But these countries demonstrate that it is possible to have voter ID rules that do not unfairly impose costs or restrictions on any group of citizens, and which are broadly accepted by the public.

But here’s the rub. These European rules work because every citizen already has a state-issued ID, and because the law requires them to carry it around all the time regardless of whether they are going to vote or just popping down to the panetteria for cannoli and café au lait.

When the Hawke government attempted to introduce a similar ID initiative in 1985 – the Australia Card – it was howled down by those who saw it as an unreasonable invasion of privacy and a dangerous consolidation of personal data. The Howard government also briefly revived the idea in 2006 as part of a suite of anti-terrorism measures prompted by September 11 and the Bali bombings. But even Howard’s own cabinet couldn’t unite behind the proposal; his attorney-general, Philip Ruddock, stated that a national ID “could increase the risk of fraud because only one document would need to be counterfeited to establish identity.”

One could muse at length on why Australians are so much more concerned about privacy and data security than the millions of Europeans who carry a national ID every day. But the fact remains that governments on both sides of the political divide have tried and failed to introduce such an ID scheme in the past, to the point where this is now seen as an almost untouchable policy in the Australian political arena.

None of the Australian proponents of voter ID laws have mentioned linking this to a broader national ID initiative. Nor would we expect them to in the current environment of fiscal austerity, given the huge costs involved in developing the infrastructure for this and distributing the cards to all Australians. But if the Coalition were serious about designing a voter ID scheme that doesn’t impose costs on already-marginalised groups, and avoids the public disquiet seen in America, then the lessons of Europe are theirs for the taking.

ONE FINAL point is worth making. To engage in a discussion about voter ID at all is to cede ground in some ways to those who support the idea. After all, if we’re talking about what kinds of laws will work best to stop fraud, then we are implicitly accepting the premise that fraud occurs. The AEC’s revelations about multiple voting at the 2013 federal election confirm that a very small number of ballots were improperly cast; on that basis we can probably assume that there are a handful of voters who do the wrong thing at every federal election.

But to extrapolate from that to the idea of widespread voter fraud is to make a conceptual leap that is simply not supported by the evidence. Since 1983, when most of the current electoral rules and processes were introduced, there has never been an instance where alleged or proven voter fraud led to the overturning of a declared seat result. That is to say, in the past thirty years, neither the AEC nor any party or candidate has ever identified enough voting discrepancies to successfully pursue a case through the Court of Disputed Returns. Our system may not entirely prevent improper voting, but it is well set up to detect it and ensure that it does not affect the actual outcome – surely the true metric by which electoral integrity should be judged.

The Coalition’s overtures on voter ID are premised on a moral panic, pure and simple. It is understandable that Australians would have questions about our electoral system in the wake of the WA Senate stuff-up. But the answer doesn’t lie in conspiracy theories and half-baked measures that pay little mind to the legal and organisational realities of running elections in Australia.

The real answer lies in helping Australian voters understand more about how our system works and about the checks and safeguards already in place. The simple fact is that Australia needs voter identification laws about as much as Clive Palmer needs photo ID to board his personal plane. Anyone who suggests otherwise deserves to be taken about as seriously as Clive Palmer usually is. •