Do televised political debates make a difference? They must, in the sense that everything, big and small, changes something, even if subliminally.

But do they have meaningful electoral significance?

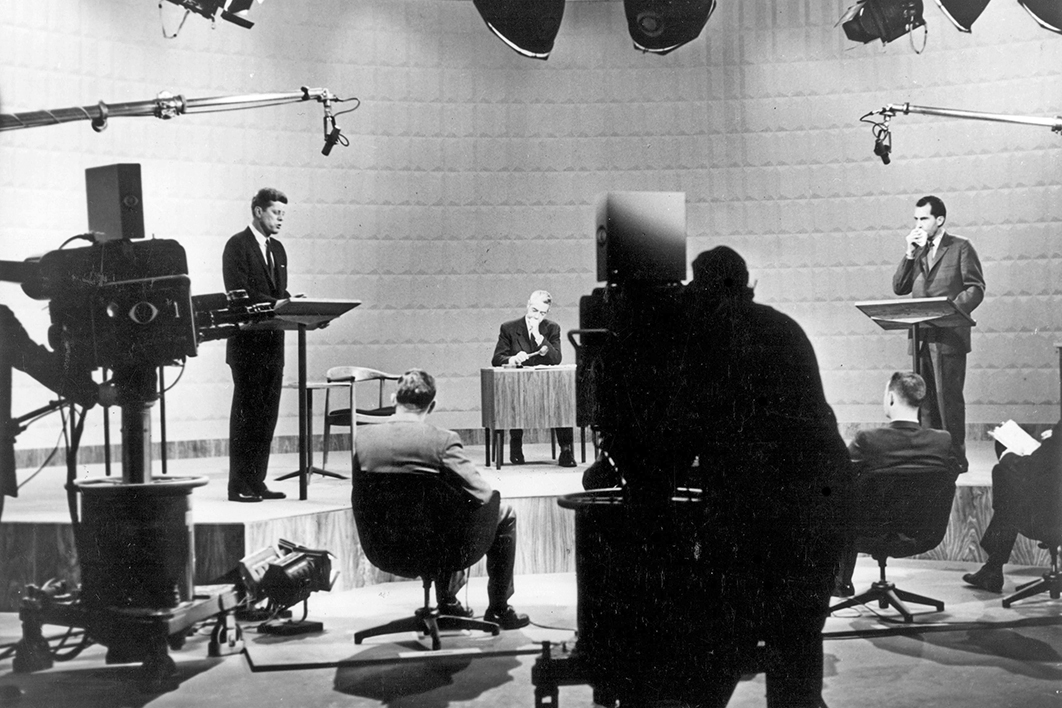

It’s a question that’s been asked and analysed in America since the very first ones, Nixon versus Kennedy, sixty years ago, and opinions still differ.

The first Australian debates came a generation later, in 1984, at Bob Hawke’s first election as prime minister. Liberal leader Andrew Peacock was perceived to do well, and his party went on to outperform expectations at the ballot box, and that was good enough for some commentators to detect cause and effect. At the next election, in 1987, when he was facing John Howard, Hawke gave the debates a miss. But he did participate when Peacock was back in the job in 1990.

Howard, who went on to be the most electorally successful prime minister of the modern era, was pretty awful at these things — when he was prime minister. His best performance was as opposition leader in 1996; he was the plucky guy who took the fight up to the colossus, Paul Keating.

In office, though, he was most comfortable alone on the podium, exercising quiet, contained authority, massaging the press gallery like putty in his hand. When he had to share equal footing with the challenger, he shrank before our eyes.

Howard was an extreme example of the pattern with debates in this country: incumbents perform poorly; challengers make the most of their moment of equality. And it doesn’t seem to make much difference anyway.

Early this year, Bernie Sanders supporters warned that if Joe Biden won the Democratic nomination, Donald Trump would “destroy” him in the debates. You could just picture it, couldn’t you? The president free-forming comedian-style, battering a hapless “sleepy Joe” barely able to form a coherent sentence.

And that did seem to be Trump’s strategy last week. As he found out, though, these events don’t really work like that. Both sides are entitled to their two minutes uninterrupted; you can’t just shout over them. Well, you can, but it isn’t as successful as you might expect. In fact, Trump’s seemingly unhinged demeanour distracted attention from Biden’s inevitable gaffes on law and order and the green new deal.

Politics as hand-to-hand combat — waiting for that knockout blow, or at least a technical knockout — is a template much favoured by political observers. Put another way, both sides put on a show, and on polling day electors hold up their score cards. But elections are just as much about choosing between the lesser of two evils as they are about enthusiasm for the winner — as much about not stopping votes from coming your way as about impressing people. (This applies even more in Australia with compulsory voting.)

There are no knockouts.

For almost four years after the shock 2016 result in the United States, a thriving school of thought saw Trump as a political genius who played the liberal media like a violin. Progressives, alienated from everyday Americans, were his secret weapon. It’s an old boast by conservatives around the world (switching, if they lose, to complaints that the left-wing media didn’t give their candidate a chance), but the current version was also taken up by what can be described as the anti-anti-Trump left, many of whom were Sanders supporters.

“Trump will devour Biden” is giving way to “Okay, so Biden will win, but he’ll be at least as bad as Trump.”

In truth, the identity of the sitting president is the only reason Biden is so far ahead in the polls. Any other cardboard cut-out Republican would be more competitive against this Democratic candidate, and most of them would have more easily defeated Hillary Clinton four years ago. That’s another fallacy that flows after an election: only that candidate, that leader, could have won.

Clinton, by the way — for what it’s worth — was roundly thought to have won all three 2016 debates. •