For those who argue that the Turnbull government has no political nous, the proposed changes to Australian citizenship offer strong counterevidence. Modifying citizenship, not only by appealing to “values” but also, more substantively, by formalising an English-language test, will undoubtedly prove a popular move. After all, if you ask people what it means to be Australian – as an ANUPoll did in 2015 – one answer stands out above all: the ability to speak English. But what do the changes mean for migrants?

The new English-language requirement represents “a significant change” from the basic skill required at the moment, says immigration minister Peter Dutton. “We increase that to IELTS Level 6 equivalent, so that is at a competent English-language proficiency level, and I think there would be wide support for that as well.”

He’s not wrong. This is not just a significant change; it is a fundamental break. To see why, you have to understand how high a barrier Level 6 of the IELTS – the International English Language Testing System – will be for many new migrants.

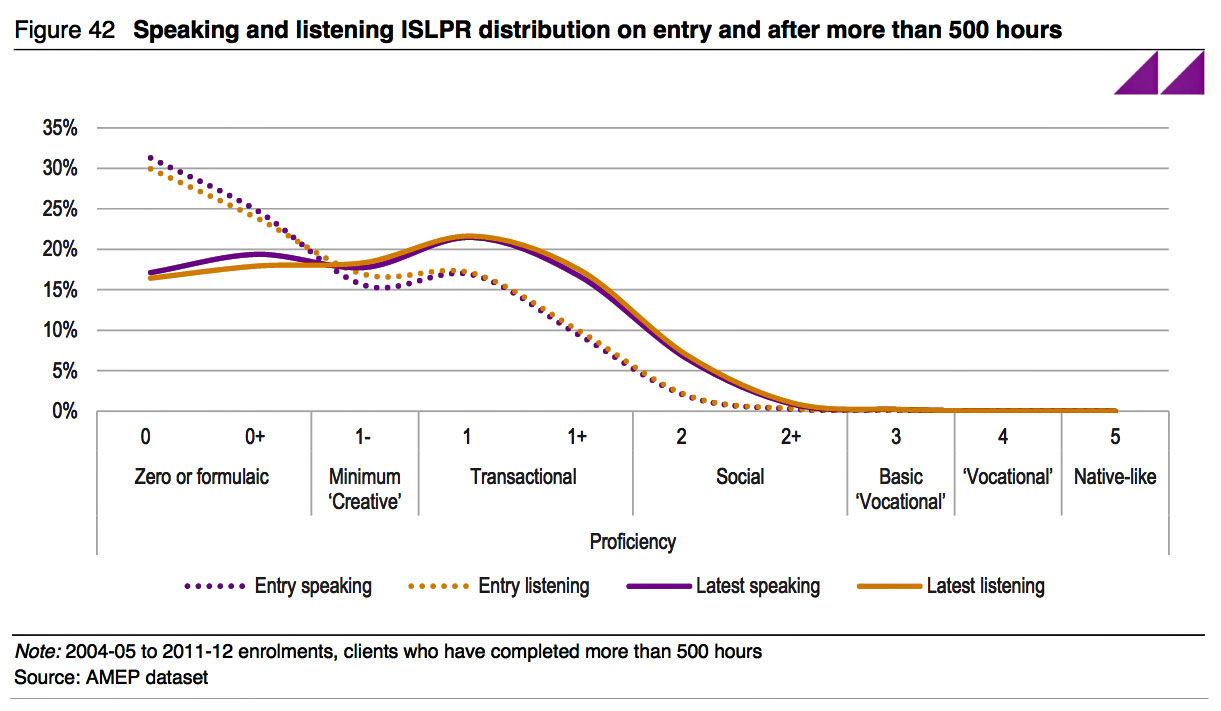

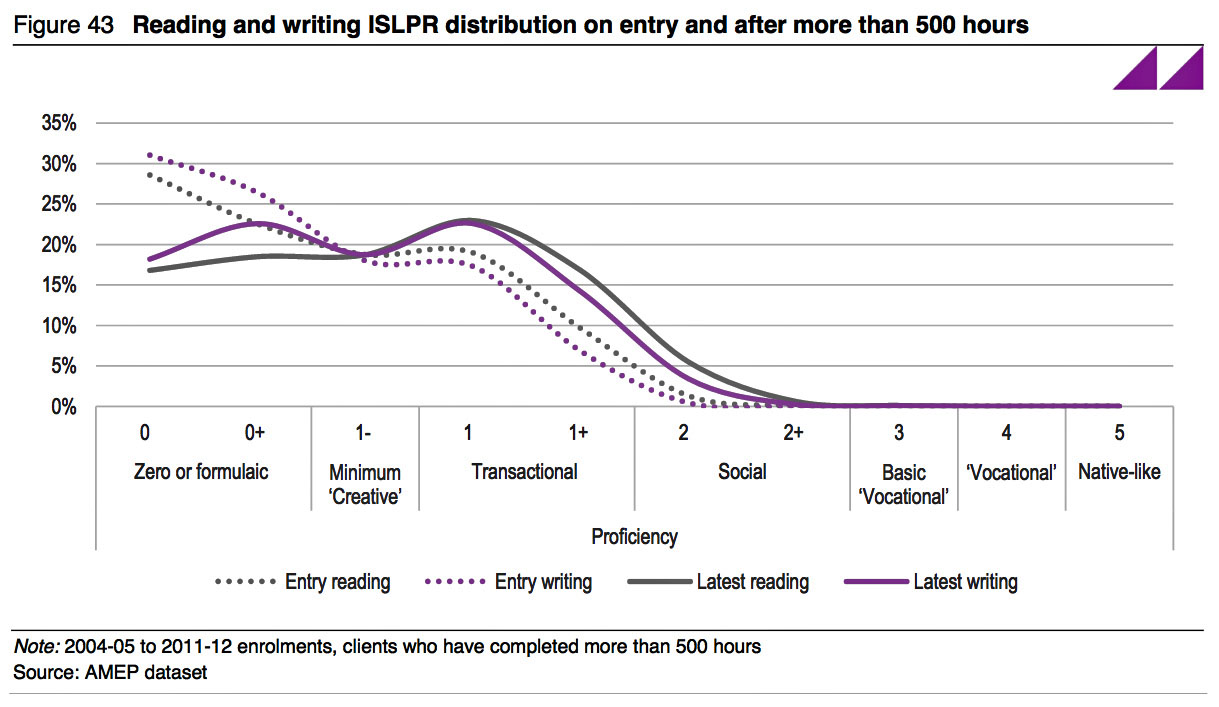

In 2015, ACIL Allen Consulting evaluated the Adult Migrant English Program, or AMEP. Its report is the most up-to-date assessment of the English literacy of recent migrants. Unfortunately, AMEP doesn’t use the IELTS system, so a clean comparison of new migrants’ scores isn’t possible. Instead, we need to translate AMEP’s system, the International Second Language Proficiency Rating, or ISLPR, into IELTS equivalents using what information we can find on the public record:

• Answering a 2006 Senate estimates question, the immigration department said an ISLPR 2 is approximately equal to IELTS 4 or 5.

• In the ACIL Allen review, an AMEP service provider is quoted as saying that an “ISLPR 2” is equal to IELTS 4.5.

• In a submission to the Productivity Commission’s migration intake inquiry, David Ingram, a linguist who was involved in devising both of these language testing systems, said that “universities that require IELTS 6 for entry to particular courses usually require 3 in all macroskills on the ISLPR.”

We can infer that IELTS 6, the level of English proposed by the Turnbull government to be eligible for Australian citizenship, is equal to ISLPR 3. And what proportion of new migrants get a score of ISLPR 3 after completing their government-allotted 500 hours of English training in the AMEP?

None. Zero per cent. Of the AMEP attendees who completed 500 hours of training between 2004 and 2012, 0 per cent of new migrants reached the level required for the new citizenship test.

As ACIL Allen found, 28 per cent of AMEP clients leave the program with scores of 0 or 0+ (“zero or formulaic,” the lowest levels of proficiency) on all four ISLPR elements: reading, writing, listening and speaking. Just 7 per cent of clients exit at ISLPR 2 (social proficiency, the equivalent of IELTS 4.5) after receiving 500 hours.

The Adult Migrant English Program’s performance in reducing the proportion of clients scoring at the lowest levels (0 or 0+) on the International Second Language Proficiency Rating, or ISLPR.

Source: AMEP Evaluation: Report to the Department of Education and Training, ACIL Allen Consulting, May 2015.

In 2004–05, about 20,000 new migrants enrolled in AMEP, a number that grew to about 30,000 in 2011–12. Sixty per cent of the new migrants in AMEP classes are women and children. Of course, many new migrants do not attend AMEP classes for a variety of reasons. In 2014–15, about 80 per cent of eligible humanitarian migrants, 20 per cent of eligible family migrants and 8 per cent of eligible skilled migrants attended AMEP.

What these figures show is that somewhere north of 30,000 people each year would be ineligible for Australian citizenship under the new rules. While a proportion will increase their English proficiency with time, outside the classroom, language proficiency research shows that this is a slow and gruelling process.

Using conservative estimates of the three key elements – AMEP enrolment trends, the rate of English proficiency improvement over time, and net migration trends – anywhere between 30,000 and 40,000 new migrants each year are highly unlikely to meet the proposed English proficiency level for Australian citizenship in their first decade of settlement.

Over time, this will generate a growing population of people excluded from citizenship. It’s impossible to say with any certainty what this will look like over the long term, but the available evidence suggests a substantial number of people will never receive Australian citizenship.

Some people might say these new migrants will simply have to learn and this is a good incentive to get it right. This “tough love” argument should be called out for what it is: a willingness to see people permanently excluded from our society. No voting. No standing for public office. Exclusion from many public service jobs. The possibility of expulsion from Australia by visa cancellation.

Given that 35 per cent of humanitarian migrants score the equivalent of an IELTS 2 after their AMEP classes finish, the new rules will specifically refuse citizenship to a significant proportion of refugee migrants to Australia. This is despite the fact that the figures reveal that refugees appear to love Australia more than any other group of migrants – at least if you measure this according to their higher propensity to seek citizenship.

Others might say this means we need to give people much more English-language support and training. Perhaps this is true. But we also need to recognise that coming to a new country is really difficult. It’s hard enough for rich, English-speaking migrants. But think about a Sudanese single mother with four children who is illiterate in her own language. To introduce a formal English-language test requiring IELTS 6 is to tell this woman she isn’t welcome as an Australian citizen. And if you think this is a handpicked example on the margins of our migration program, Australia granted 1277 “Woman at Risk” visas in 2015–16 as part of the annual humanitarian program, for “protection of refugee women who are in particularly vulnerable situations.”

And this doesn’t even get into the potential for married couples to be separated by an English-language test, or for children to pass easily but have to watch their parents excluded.

IELTS Level 6 is by no means perfect English. You can read this practice essay and scoff, if you like, at the simple errors highlighted. The official definition is this:

Generally, you have an effective command of the language despite some inaccuracies, inappropriate usage and misunderstandings. You can use and understand fairly complex language, particularly in familiar situations.

But the practical effects of imposing this standard are immense. It amounts to the deliberate exclusion of thousands of new migrants from Australian citizenship. Back in 2015, on the same topic, I wrote, “The worst outcome is permanent exclusion from society because barriers to entry are too high. An English-language test for citizenship would be such a barrier. This exclusion would occur despite an indefinite right to remain in Australia. A tiered, broken system of residency with little long-term hope.”

While almost all Australians believe speaking English is an important part of what makes someone an Australian, is this the type of society we want to live in? •