My son, who is studying in London, was amused recently when an ad popped up on his social media feed encouraging him to head to Australia for a working holiday. The algorithm was sophisticated enough to track his interest in Australia but not smart enough to realise he’s a citizen with no need of a visa.

The fifteen-second video shows a young Englishman — hiking, working, drinking and snorkelling — who declares that “taking the risk” on an Aussie working holiday visa helped him find a new lust for life by escaping office work and becoming a landscape gardener.

Linked to Tourism Australia’s Guide to an Aussie Working Holiday, the promo seems less about vacations than the idea of living and working in Australia for an extended period. Perhaps the Australian government’s official tourist agency doesn’t talk much with the Department of Home Affairs: the campaign to get more Brits to Australia certainly seems at odds with the government’s concerns about immigration being too high.

In fact, education minister Jason Clare has singled out backpackers as one of three groups responsible for migration numbers blowing out beyond Treasury’s forecasts. The other two are international students — he was trying to convince the Coalition to back a cap on student numbers — and people overstaying their visas.

That third category is questionable given that Home Affairs estimates there are about 75,000 unlawful non-citizens in Australia, which is not a huge increase on pre-Covid figures, which were well down on numbers in the late 1980s, when we had far fewer tourists and barely any temporary migrants. Overstay numbers also include lots of churn, since most travellers only breach their visas for a few days or weeks. Compared to the huge flow of people in and out of Australia, they are a relatively small problem.

Perhaps the education minister was referring to the 330,000 people on bridging visas awaiting decisions from the home affairs minister, the department, the Administrative Appeals Tribunal or the courts. Although some may be engaged in rorts, many are exercising their legal right to seek a visa of the kind they want.

An asylum case, for example, can take years to wend its way through the appeals process — a fact that former immigration department deputy secretary Abul Rizvi argues has facilitated a labour-trafficking scam whereby applications for protection visas are lodged primarily to gain work rights. Other cases can be heart-rending: a mother seeking to remain in the country with her Australian-citizen children after fleeing an abusive partner, for instance, who can only have her case resolved by the personal intervention of the minister.

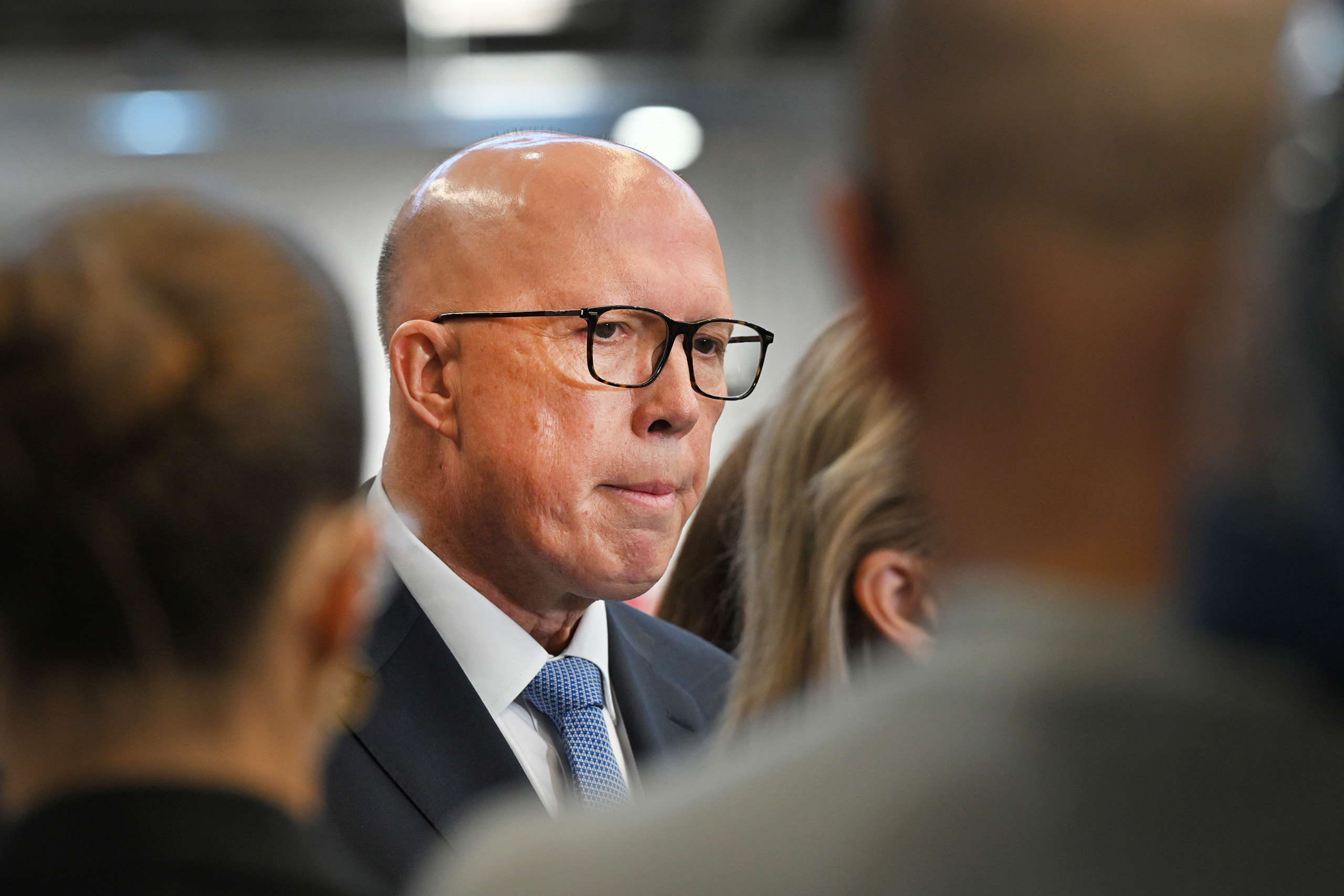

If Jason Clare was trying to prove to voters that Labor can be tough on borders, he should also have known that the Coalition would outdo him once the election campaign got underway. Stoking fears about out-of-control immigration is central to Peter Dutton’s pitch, and he sharpened the point this week when he pledged to “deal with Labor’s mess” by reducing net overseas migration by 100,000 as soon as he gets into government. That 40 per cent cut to the forecast of 260,000 comes on top of his budget-reply pledge to cut the permanent migration program by 25 per cent from 185,000 to 140,000 people.

Although those two categories, net overseas migration and permanent migration, are often confused, it’s important to keep in mind the difference. “Permanent migration” covers the number of people who are granted permanent residency each year, many of whom already live in Australia. “Net overseas migration,” by contrast, measures the difference between the number of people coming to Australia for a year or more and the number leaving. That figure generally excludes tourists but takes in the entry or exit of Australian citizens, permanent residents, working holiday-makers, international students, New Zealanders, skilled workers, asylum seekers and others.

Tourism Australia’s backpacker promotion not only challenges Dutton’s claim that the numbers can quickly and easily be reduced but also his assertion that the surge in net overseas migration is Labor’s fault. It’s a fair bet that the English lad can swap his boring office job for landscape gardening because British backpackers benefit from exceptional treatment under Australia’s working holiday program. Unlike young travellers from other countries, UK citizens can qualify for second and third working holiday visas without having to spend time doing specified work, like fruit picking, in a regional area.

Young Brits, in other words, can live and work in Australia for three years without jumping through hoops. What’s more, the age limit for them is thirty-five, whereas for most countries it’s thirty. This generous treatment probably explains why the number of UK citizens applying for a first working holiday visa jumped by almost a third last financial year — a far greater rise than for any other nationality, bringing their numbers to more than a one in four applications.

The upshot is that about 55,000 UK citizens are in Australia on working holiday visas, an increase of nearly two-thirds since March last year, or more than four times the rate of increase for all other nationalities combined. Their numbers are likely to keep climbing as awareness of the new rules spreads and more young Britons prolong their stay in Australia.

Why not simply change the rules to reduce numbers? Well, working holiday-maker programs are included in bilateral agreements between Australia and other nations, so revoking or drastically altering them has implications for diplomatic relations. Eighteen countries were added to Australia’s working holiday scheme during the Coalition’s last term in office, and Peter Dutton was either immigration minister or home affairs minister for more than six years during that time. It was Coalition governments that made it possible for working holiday-makers to extend their visas — initially, in 2005, for one extra year, and then, in 2019, for two. The range of occupations that qualify backpackers for second and third visas was also broadened repeatedly under the Coalition.

As for the rule that allows UK citizens to extend their visas without doing designated work in a regional area: that was part of the Marmite-for-Vegemite UK–Australia free-trade deal negotiated between prime ministers Boris Johnson and Scott Morrison in 2021.

So, if backpacker numbers are a mess, it’s the Coalition’s mess, and Peter Dutton is stuck with it unless he wants to give allies Trumpian treatment. If he did try to slash working holiday numbers he would also provoke a run-in with his National Party colleagues, whose supporters in regional and remote Australia rely on backpackers to plug a range of labour shortages in industries like horticulture, meat processing and tourism.

Cutting another category of temporary migration — the skilled stream —is equally difficult. Not only would it annoy industries that rely on skilled workers to run and expand their businesses, but it overlooks the fact that the numbers in this category (87,000 primary visa-holders as of December 2024) are relatively small.

New Zealanders represent a much larger group of temporary residents — more than 700,000 at last count — but again, this is not a figure that can be easily reduced unless the Coalition wants to rip up the Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement that has enabled Australians and New Zealanders to live and work in each other’s countries for more than half a century.

But perhaps Peter Dutton could cut 100,000 from the net migration by reducing the backlog of people on bridging visas? This would be welcome, because people waiting on life-changing decisions would finally get answers from the government. It would also help to weed out rorts. Again, though, this isn’t straightforward: to get faster departmental decisions, speedier tribunal reviews and swifter removals from Australia, the Coalition would need to spend a lot more on extra staff, which contradicts its pledge to reduce public service numbers by 41,000.

Cutting the permanent migration program is no easier. About 70 per cent of the permanent program is made up of skilled migration, the other 30 per cent family migration. Both sides of politics have put great emphasis on the importance of imported skills for growth and productivity, and cuts in this area would upset powerful lobby groups.

It’s hard to tamper with family migration, too, since the vast bulk of family migrants are the wives, husbands, fiancés and other intimate partners of Australian citizens and permanent residents. As Abul Rizvi points out, ministers can’t lawfully cap partner visa numbers, or even direct the department to go slow on processing them. The only “easy” cut to the permanent program would be to reduce the annual humanitarian intake from 20,000 to 13,750, the level it was when the Coalition was last in office.

These difficulties indicate why Labor and the Coalition have both targeted the categories over which they have more influence, international students and graduates. At the end of Covid, the Morrison government coaxed students back to Australia by allowing them to work for forty hours each week rather than twenty. Along with the Morrison-era “Covid visa,” designed to keep temporary migrants working through the pandemic, these looser rules boosted net migration — though Australia’s overall population in 2025 is pretty much in line with the pre-Covid forecasts.

Despite the Coalition’s refusal to support Labor’s proposed cap on international student numbers, the government took several steps to slow student arrivals and encourage departures. It jacked up the level of savings international students need to qualify for a visa from $21,041 to $29,710 and pegged it at 75 per cent of the national minimum wage. It more than doubled non-refundable student visa application fees from $710 to $1600 and increased the pass mark in English-language tests for undergraduate visas and post-study work visas. It tightened eligibility for post-study work visas and made it harder for students and other temporary migrants to extend their stay in Australia by hopping from one visa to another.

Higher education expert Andrew Norton reckons the effect of these government measures is already apparent. Student visa applications for the first two months of this year are well down on the same period in the previous two years and well down on pre-Covid numbers. In that light, the Coalition’s plan to increase student visa application fees to $5000 and cap international enrolments looks like overkill. In fact, Peter McDonald and Alan Gamlen from the ANU Migration Hub predict departures by temporary visa holders will spike in 2027 and, without government action, migration could fall to record lows, with all that entails.

With migration, it’s often a case of being careful what you wish for. •