Part of our collection of articles on Australian history’s missing women, in collaboration with the Australian Dictionary of Biography

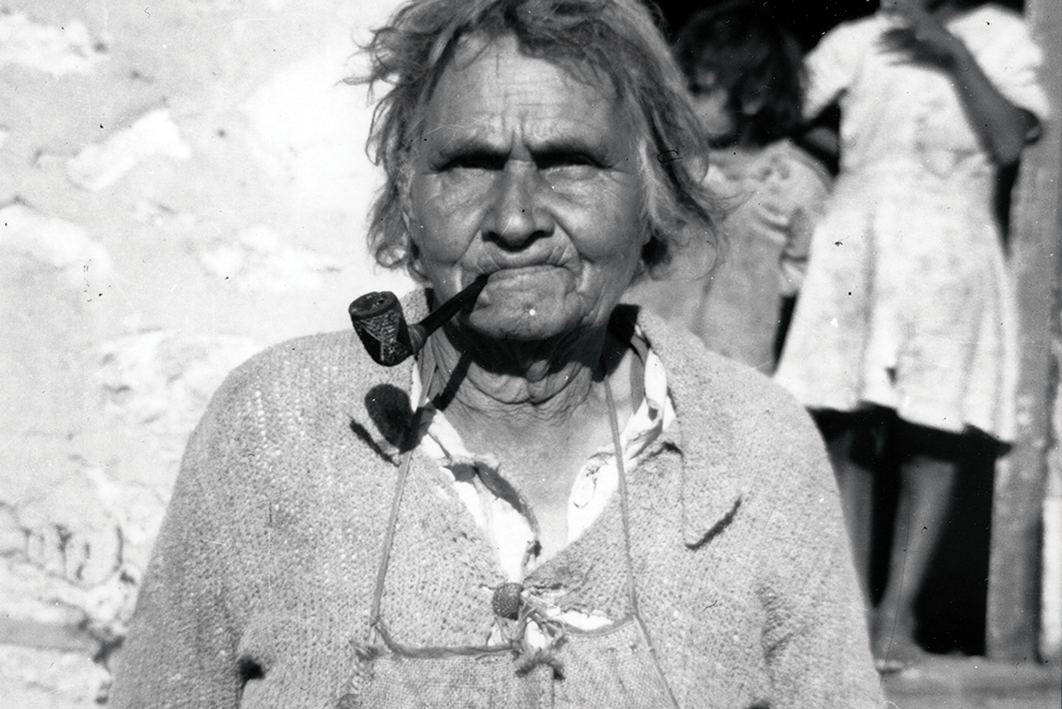

Pinkie Mack was in her early nineties when she performed a corroboree in front of more than 8000 people with a group of twenty-one male dancers from Raukkan (Point McLeay Mission). It was 1951, and the occasion was a re-enactment of British explorer Charles Sturt’s arrival at Goolwa, on the western shores of Lake Alexandrina, 120 years earlier. Mack was a renowned song woman with deep cultural knowledge, much of it passed down from her mother, Queen Louisa Karpeny (1821–1921), known as Ngewatainindjeri, who had witnessed Sturt’s arrival in the lands of the Ngarrindjeri nation in 1831.

Mack was born Katipelvild at Marrunggung (Brinkley Homestead), where the Murray flows into Lake Alexandrina in Yaraldi-speaking country, in 1858. A member of the Piltindjeri clan, she acknowledged Yakapeni (a variation of Karpeny) as her father, and she and three younger sisters lived in his camp after the onset of puberty. Through Yakapeni she learnt a range of songs and ceremonies. Marrunggung was downstream from Wellington, where her biological father, a Scottish-born policeman, George Mason, was the first sub-protector of Aborigines. Louisa Karpeny and George Mason had two children, George and Margaret, known as “Pinkie” for her fair skin.

Pinkie briefly attended school at Point McLeay Mission, whose founder, George Taplin, challenged many Ngarrindjeri cultural practices, as did his son when he succeeded him. (The mission’s questionable practices during this period were eventually the subject of a government inquiry.) She was known as Pinkie Karpeny until her marriage to her first husband, Telwara (Djelwara) John Mack (c. 1840–1918), a Yakamuldah man whose country was upriver, east of Mildura, near Kalkine (Culcairn Station).

The couple lived near Mildura and Wentworth and had at least four sons — Albert (born 1886); David (1887–1911), who died from consumption as a young man; Miller (1891–1919), who saw service on the Western Front in 1916–17 but died of tuberculosis on his return; and Arthur (1895–96), who died from meningitis as a baby — and at least two daughters — Rose and Edith, born possibly between 1888 and 1890.

Pinkie kept the name Mack for the remainder of her life as a signifier of the upriver knowledge of songs, ceremonies and designs she had acquired. A second marriage, to Nginmelindjeri Philip Sumner (1864–1921), resulted in at least two sons — Benjamin Philip (1903–06), who died of whooping cough, and Hurtle (born 1908) — and at least four daughters — Ellen (born 1905), Laura Isabella (born 1906), Wilhelmina (born 1911) and Nita Louisa (born 1913). She later lived with a younger man, Alfred Cameron junior (born 1890).

By the early 1920s, then in her early sixties, Pinkie was a practising midwife, and would eventually attend the births of seventy-two babies. Records show that most women in her care quickly recuperated, with Mack and attendants wrapping the newborn in fur and assisting in the mother’s recovery.

Like her mother, Mack was a key informant for the South Australian Museum. In 1933–34, camped at Wellington, she was among those who began mapping Yaraldi clan and place names with Norman Tindale, an ethnologist with the museum. Mack delineated Yaraldi country as the eastern side of the Lower Murray — from Murray Bridge, upstream of Tagalang (Tailem Bend), downriver through Wellington to Marrunggung and onto Lake Alexandrina, crossing into Lake Albert — as well as all the clan areas along the Coorong, on the Fleurieu Peninsula and at Encounter Bay. In 1935 and 1938, Mack and a cousin, Albert Karloan, a member of the Manangki clan, related Yaraldi fishing stories and clan associations and place names.

According to Tindale, Pinkie Mack knew “more songs than any other Jaralde [Yaraldi].” Despite elaborations and melodic improvisations by other singers since then, her essential song texts, tempos and rhythms have endured, suggesting links to the deep as well as the historical past. “Pata Winema,” a song about gathering cockles at Goolwa, was sung by women at men’s initiation ceremonies — including the ceremony for Karloan, who recorded the song.

In 1943, Mack described five categories of song to the anthropologists Ronald and Catherine Berndt, noting the name of each composer. Pekeri songs, for instance, were identified by their clan tunes and comprised an even beat by women on folded skin drums or beating sticks. Her pekeri songs included the pelican (rorika) song to help cure sickness, as well as “Nganawi Ruwi,” a lament to take the Ngarrindjeri back to their country. Mack also recorded many tunggari songs, which convey different ideas, sometimes about specific historical events and phenomena.

Among the patangi songs, which were for dancing, was one composed by Pinkie’s husband John Mack that referred to upriver people coming down the Murray to meet the Ngarrindjeri. Another patangi song, composed by Minduk Jack of the Yakamuldak (near Wentworth), was about watching Europeans arrive by steamer with a buggy in order to establish Mildura. Both songs were performed when people from different areas gathered for a large ceremony.

Mortuary rites and showing respect for the dead were fundamental aspects of Ngarrindjeri culture. In the early 1940s Mack and Karloan condemned the archaeological excavation of burial mounds and camp sites on Kangaroo Island. It was believed that Ku-Ka-Kungarr, as it was known, was a step on the way to the land of the dead. Many burial sites were remembered there, including those of mass interment during the smallpox epidemic.

Mack also had experience in preparing mortuary rituals with red ochre, smoking platforms and specially prepared large oval mats. She was a talented weaver, and a large mortuary mat she wove for the Berndts in 1943 is now held at the South Australian Museum. Right up until the 1940s, she would row across the water to Tagalang (Tailem Bend) to sell her weaving to passengers on the steamers. Her weaving continued a family tradition of passing on to younger generations the loops and patterns evident in her mother’s work. Louisa Karpeny’s iconic bags, baskets and large circular mats, seen in a 1915 photograph, were reminiscent of the circular mats described by Charles Sturt in 1833 and by artist George Angus in 1844. Mack passed on these weaving skills to her daughter Ellen Brown (nee Sumner, 1905–79), to Ellen’s daughter, Daisy Rankine (born 1936), and then to Daisy’s daughter Ellen Trevorrow (born 1955), continuing a distinguished line of weavers.

Mack’s cultural knowledge was also embedded in her hunting and skinning skills, as well as dancing for pleasure and in women’s initiation ceremonies. Like other Ngarrindjeri men and women, she knew how to prepare a pelican skin by salting, nailing and stretching it to dry. But she did not claim to represent all Ngarrindjeri women’s cultural knowledge, nor women’s rituals specific to other clans. The Berndts described Mack as a “gregarious… most likeable, affectionate and energetic person” and “a memorable collaborator.”

For Pinkie Mack, her family recalls, the 1951 performance must have been a moment of mixed emotions, of sorrow and sadness, mourning the loss of land and ceremony as well as affirming her cultural heritage. Sturt’s arrival in 1831 had led to much dispossession. As Pinkie Mack sang in Yaraldi, chanted, beat the rhythm and danced, she was giving public expression to her authority as a song woman and cultural custodian. It was her last corroboree: a profound statement about the continuation of her clan’s knowledge and the ever-present state of deep and recent history; and a provocative statement that cultural knowledge, song and dance practice still ran through the land, directly in the face of Sturt’s landing at Goolwa. •

Further reading

A World That Was: The Yaraldi of the Murray River and the Lakes, South Australia, by Ronald M. Berndt and Catherine H. Berndt with John E. Stanton, Melbourne University Press, 1993

Ngarrindjeri Nation: Genealogies of Ngarrindjeri Families, by Doreen Kartinyeri, Wakefield Press, 2006

Ngarrindjeri Wurruwarrin: A World That Is, Was, and Will Be, by Diane Bell, Spinifex, 2014