Some people used the lockdown to finally get around to reading Proust or Joyce. I managed to reread Ulysses, but I also found myself tackling the less demanding works of Nevil Shute, the popular writer of the 1940s and 1950s. Shute is best known for On the Beach, his 1957 novel about a Melbourne awaiting the deadly fallout from a nuclear war in the northern hemisphere.

Many people have been reminded of that novel — or the film version starring Gregory Peck and Ava Gardner — in the depths of the pandemic lockdowns. Despite the quip that Melbourne was “the perfect place to make a film about the end of the world,” falsely attributed to Gardner, the British-born Shute showed great affection for the city, and indeed for Australia as whole.

This bestselling British author had upped sticks and moved to Australia in 1950, and would spend the last decade of his life on a property southeast of Melbourne. Starting that year with A Town Like Alice, his immensely popular books portrayed Australia as a sunny land of opportunity — and plentiful steak and eggs — contrasted with a tightly rationed Britain in the grip of complacent civil servants and envy-ridden politicians. They helped fuel the surge of “ten-pound Poms” taking up the Australian government’s offer of assisted migration. When Shute died in 1960, Sydney’s Daily Telegraph ran an editorial declaring that “this country has lost one of its greatest friends and propagandists.”

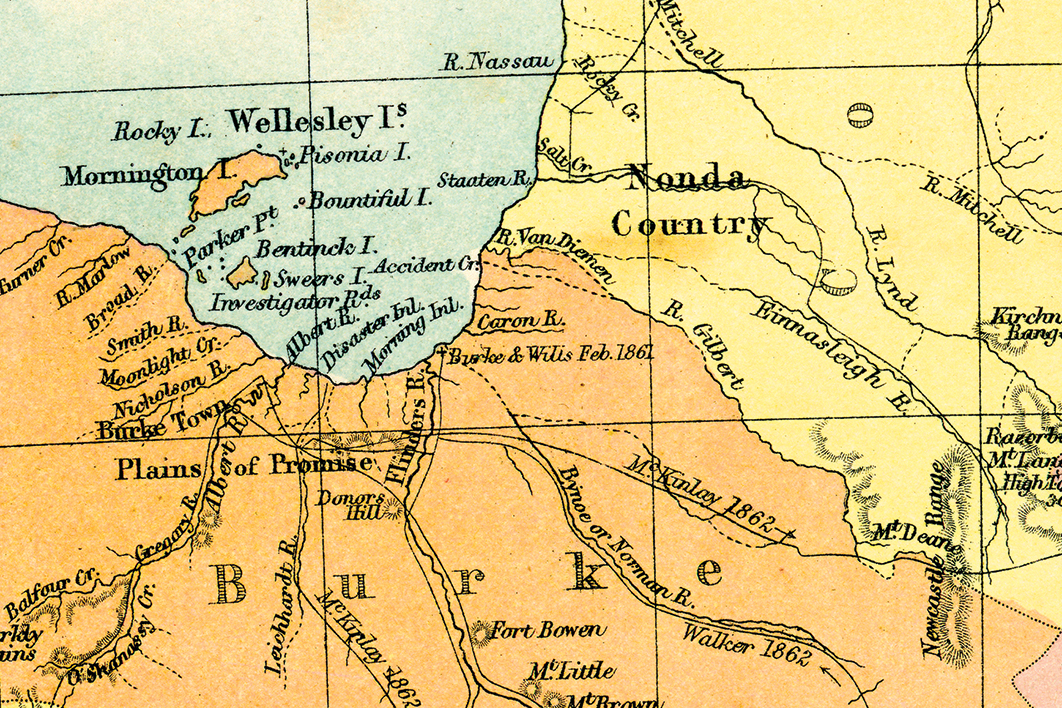

And so, when a reporting trip recently took me to Queensland, I decided to look at the unlikely place where this infatuation began: the country on the southern shores of the Gulf of Carpentaria. From November 1948 until January the following year, Shute and his friend James Riddell toured this region in a light aircraft they’d flown out from Britain. In those days, cut off during the three-month “wet” and baked dry for the rest of the year, the region’s human population counted in the hundreds.

At Normanton, not far inland, Shute and Riddell met pastoralist Jim Edwards, who had been a prisoner of war working on the Burma railway. For filching food from the Japanese, he’d been tied with wire to a tree for three days and bashed with rifle butts. He became the model for A Town Like Alice’s Joe Harman, the archetypal Australian bushman, laconic and true, played by Peter Finch in the 1956 film of the book and by Bryan Brown in the 1981 miniseries.

Immensely popular: Nevil Shute in London in 1953. Picture Post/Getty Images

Shute had also come across the story of a group of Dutch women and children who had been shunted around Sumatra for three years by the Japanese. He made them the novel’s English families, marched around Malaya by perplexed guards, with a Malay-speaking planter’s daughter, Jean Paget, assuming leadership. Barefoot, sarong-clad and, like all of Shute’s heroines, wise beyond her years, she was played by Virginia McKenna in the film and Helen Morse in the miniseries.

Shute joined his storylines in occupied Malaya, when Joe Harman, driving a truck for the Japanese, steals his commandant’s chickens to feed Paget’s group. He is caught, nailed through the hands to a post and left to die. Although he is rescued, he only learns much later that Paget and her group survived — and, moreover, that she was Miss Paget, not Mrs as he’d assumed.

Back running a cattle lease in the Gulf, Joe scores a modest lottery win and sets off to London to track her down. Meanwhile, Jean, now a secretary in a London leather-goods firm, has come into an inheritance (another favourite Shute plot device) and goes back to Malaya to repay the villagers who sheltered her group. Having learned that Joe had survived, she travels on to Australia to find him, first to Alice Springs and then to “Willstown,” where he now works.

After many crossed wires the pair meet in Cairns. Joe is somewhat awed by the smart English lady Jean has become, but the ice is finally broken on Green Island in the Great Barrier Reef when Jean dresses in her old sarong. Though the gates of passion open, they agree to wait until they are married.

Shute’s love affairs were always chaste until marriage. He boycotted the premiere of On the Beach because its director, Stanley Kramer, had the US nuclear submarine commander, played by Peck, consummate his relationship with his Australian friend, played by Gardner, instead of staying loyal to his wife, presumed dead in America.

Leaving Cairns and Green Island, Joe and Jean return to “Willstown,” where Jean sets out to revive the old mining town and make it “a town like Alice.” Her scheme is to set up a shoe-making factory using the handy local supply of crocodile skins and employing girls who would otherwise head for the big cities. With a supply of young white women enticed further by a new ice-cream parlour, open-air cinema and hair salon, young white men also throng to Willstown. Soon new houses are going up on abandoned lots and the footpaths are full of prams.

To get to the original of that fictionalised place, I take the Trans North bus from Cairns to Normanton, then rent a four-wheel drive with a strong bull bar for a 230-kilometre journey along Australia’s national Highway 1, hereabouts called the Savannah Way. If you follow for the next 13,000 kilometres, as a lot of grey nomads do, it will take you around the edge of Australia and bring you back to the same place.

Highway 1 is sealed by the Queensland state government from Cairns to Normanton. But from there to the Northern Territory border, about 700 kilometres, it is left to the two local shires to maintain, a task clearly beyond the means of their few hundred ratepayers. Strips of bitumen alternate with gravel and dried mud, though most of the frequent wet-season floodways have concrete paving. The trees are stunted except along creek beds, ant hills are ranked like tombstones, a wedge-tailed eagle gorges on the carcass of one of the wallabies lying dead by the road.

Before reaching the river named after the German explorer Ludwig Leichhardt, who traversed this country in the 1840s, I turn onto a dirt track and come to a lonely monument marking the northernmost camp of Burke and Wills in their hubristic attempt to make the first south–north crossing of Australia. Across the Leichhardt, I come to a strip of sealed road that leads into Burketown, the none-too-hidden model for Willstown.

Even after seventy years, it hasn’t become a town anything like Alice. The population is just 176, with 152 more in the surrounding 40,000 square kilometres of Burke Shire — not counting the temporary residents of its Century nickel mine, the dry-season tourists, or the 1200 or so people of the Aboriginal shire of Doomadgee, to the west.

Still, it’s a great improvement on the town Shute would have seen. For one thing it has trees, thanks to a permanent water supply from a spring-fed river up-country, and a central grassy park with sprinklers pumping away. The Commonwealth Hotel, where Shute would have stayed, burnt down in 1954; in its place is the Savannah Lodge, with cabins set among thick greenery around a Southeast Asian–style open-sided lounge.

When I phone him the next morning, Burketown’s mayor, Ernie Camp, is out on his horse somewhere on his cattle spread. He tells me that when he was a small boy in the 1960s conditions were still primitive. “If you wanted a power supply you had to generate your own, or use carbide or kerosene lamps.” No roads were sealed, he says, and there was a single telephone line. “You could wait up to three days to get a telephone call out.”

As in most towns across Australia with significant Indigenous populations, the local Aboriginal people lived in shanty settlements out of sight. “I can remember coming into Burketown as a kid and seeing a complex of buildings just outside town,” Camp says. “Most people referred to it as a compound.” The only Aboriginal people in Shute’s novel are out on the cattle stations, as stockmen or as domestic servants in the homesteads, speaking broken English, subservient, and bearing offensive joke names like Bournville and Palmolive.

“People here were pretty much enslaved out on stations,” community leader Murrandoo Yanner tells me later that day at the offices of the Carpentaria Aboriginal Land Council. “They used to pay the mob in opium. Then they switched to paying us in tobacco, flour, sugar and tea, and one uniform a year. You got a pair of boots, a hat, and pastoral clothes.”

Murrandoo Yanner, who assumed community leadership after the death of his father Philip in 1991. Anna Rogers/Newspix

“We were all out on the fringes, on reserves on the edge of town,” recalls Yanner, whose first name means “whirlwind” or “waterspout” and replaces the “Jayson” he was first given.

His great-grandmother brought her children into Burketown after a massacre of Aborigines, including her husband, by police and pastoralists early last century. This was not the last clash: only five years before Shute’s visit, on Bentinck Island some forty kilometres from Burketown, spear-wielding Aborigines confronted a launch carrying Australian air force radar technicians from Mornington Island. They thought that the men, who had stopped for water on their way to Burketown, were about to abuse their women like a previous army survey team had done. One Aboriginal man was shot dead.

“It was worse than Soweto,” Yanner says of the fringe camp. “No water, no sewerage, you had to walk kilometres to get your water in buckets. Pit toilets, housing just tin shacks. People used to live off the land basically, aside from the rations they used to drop off. People controlling the rations would often rort that, keep half of it and sell it on the sly in the black market to their white mates.”

Shute didn’t show us this side of his Willstown, though he has entrepreneurial Jean Paget set up a separate space for Aboriginal customers in her ice-cream parlour, with an Aboriginal girl serving. Throughout A Town Like Alice, he used pejorative white Australian terms — “boongs” or “Abos” — while showing surprising understanding and respect for Malays and even putting some of the Japanese guards in a sympathetic light. The Aboriginal locals were just part of the background.

Shute was not outstandingly racist for his times. In an earlier novel, The Chequer Board (1947), he explored two examples of interracial marriage, a Black GI to an English girl, an English airman to a Burmese woman. In another of his Australian novels, Beyond the Black Stump (1956), he lampoons an American family for their appalled reaction when his Australian heroine mentions that her pastoralist father had fathered several children with an Aboriginal woman before her white mother arrived on the scene.

In a second novel derived from his time in the Gulf country, the weird and largely forgotten In the Wet (1953), he has a baby born to a Scottish stockman and his “half-caste” wife rising to become squadron leader David Anderson in the Royal Australian Air Force three decades later.

In the Wet’s picture of Britain in the imagined 1983 is grim, with rationing continuing under a miserable Labour government and pasty-faced people shuffling in bus queues. The white “dominions” are forging ahead, meanwhile, with the populations of Australia and Canada growing to near parity with Britain. Their dynamism is thanks to a modification of democracy, started in Australia, whereby one person, one vote is augmented by extra votes for having a university degree, overseas experience, raising two children to fourteen without getting a divorce, earning more than £5000 a year, being active in church, or being rewarded by royal decree.

As British prime minister Iorwerth Jones tightens the purse strings on the royal family, the Australian and Canadian governments, royalist to their bootstraps, each chip in a fully crewed jet airliner of the latest design (somehow this miserable Britain is still making advanced aircraft) for the Queen’s Flight regiment. When Anderson is tapped to fly the RAAF’s royal airliner, he asks if his race might be a problem. After all, he is a “quadroon” and commonly known as “Nigger” Anderson among his mates. Not at all, you just look a bit tanned, says Group Captain Cox, the Queen’s Flight commander. “We aren’t asking you to marry into the Royal Family.”

The dominions’ gesture only makes things worse for the royals. They secretly leave Britain aboard the two aircraft, Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip travelling to Canberra in a jet piloted by Anderson and installing themselves at the vice-regal residence, while Prince Charles and Princess Anne disperse to Canada and Kenya. Her Majesty then appoints a tough army general, risen from the ranks, as governor-general of Britain.

Anderson meanwhile marries a Buckingham Palace secretary (another example of Shute’s stock heroine, a wise but intrepid young woman) who travels out with the Queen. She has checked out the possibility of a “throwback” baby, and been assured this could only happen if she too had non-European ancestry. On the flight out to Australia, it is Anderson who discovers a bomb in the cargo bay. “He was one quarter Aboriginal,” writes Shute, “not wholly of European stock, and in some directions his perceptions and his sensibilities were stronger than in ordinary men.” A 1970s movie version would have had a didgeridoo playing at this point.

In the Wet is the most bitter expression of Shute’s hatred of Clement Atlee’s Labour government and the welfare state bureaucracy he left behind. His autobiography, Slide Rule (1954), about his earlier career as an aircraft engineer, helps explain that hostility. During 1924–30 Shute had helped build a prototype airship, the British answer to Germany’s zeppelins, which made a successful flight to Canada. The rival public sector project, lavished with funding, crashed on its maiden voyage to India, with great loss of life.

Shute then founded his own aircraft company, Airspeed, and much of the book is about his struggle to raise capital. Government and banks were hopeless, he found, and the best source of funds was people with inherited wealth — the class found on the hunting field, the Cresta Run, the horse races and the yachting events. But they, he believed, were being taxed out of existence.

Tax was hitting Shute hard too. Having sold his shares in Airspeed for £3 million, and with his novels selling more than 100,000 copies in their first print runs and film deals starting to come in, he was a very wealthy man when he turned to full-time writing after spending the war thinking up fanciful weapons for the Royal Navy. By 1950, when he departed Britain, the top marginal tax rate was nineteen shillings and sixpence in the pound, or 97.5 per cent. Australia’s top rate was a less confiscatory 67 per cent.

He and his family settled on a small farm at Langwarrin, on the eastern side of Port Philip Bay, where he turned out more novels about Australia featuring lonely men and women finding each other in times of war or natural disaster, sprinkled with jibes at Atlee’s government and the miseries of postwar Britain.

Alice revisited: Bryan Brown and Helen Morse in Seven’s 1981 version.

While the British public lapped it up — A Town Like Alice sold 1.5 million copies — Shute’s infatuation with his new home country came to irk critics back in London. In Australia, though, there is little evidence that Shute’s portrayal was too cloying. It fed into self-laudatory stereotypes for decades, fuelling the huge popularity of the Seven Network’s 1981 miniseries of A Town Like Alice.

By then, of course, the country had changed in ways Shute couldn’t have envisaged. The exercise of Crown reserve powers in 1975, though not as drastic as the events in In the Wet, made us much more equivocal about the monarchy. The European migrants who figure in The Far Country (1952) had been augmented with Turks, Vietnamese and Lebanese. If he had existed, Squadron Leader (Retired) Anderson might have been joining a claim for his mother’s traditional lands. And Britain, far from being socialist, was getting tough conservative medicine from Margaret Thatcher.

Another forty years later, it’s not just the extra trees that make Burketown different. The 1967 referendum started profound social change, reinforced in economic terms by the 1992 Mabo judgement, for the Gangalidda, Garawa and Waanyi peoples of the region. “It wasn’t always pleasant to upset the status quo,” Yanner tells me. “They were very violent in the upheaval that had to occur — the agitation of the soil to bring new growth.”

I query the use of that word, violent. “The miners, the pastoralists, were applying great levels of violence,” he says. “The police would come and arrest us if we were trying to defend ourselves. We drew a line in the sand and said, ‘What more can you do to us?’ We took it on the chin, went to jail but we stood up for ourselves. Till they realised we wouldn’t take any more pushing and they started to respect us. We were just defending ourselves and our rights, we weren’t attacking them.”

Aged only nineteen, Yanner assumed community leadership after the death of his father Philip in 1991. He was harassed by the Queensland police during agitation for compensation from the big Century open-cut mine southwest of Burketown, then owned by Conzinc Riotinto — events recounted in The Gulf Country, a book by University of Queensland anthropologist Richard Martin, commissioned by Burke Shire.

At one point, the police prosecuted Yanner under an obscure fauna protection law when they found two small crocodiles in his freezer. After a magistrate dismissed the charge, the government of National Party premier Rob Borbidge, who called the High Court judges in the Mabo case “historical dills,” appealed the decision. It went to the High Court, which upheld Yanner’s traditional right to catch crocodiles.

A spate of arson attacks followed. One destroyed Yanner’s house, another the council building. In 2002, someone torched a Coolabah tree on the Albert River blazed by explorer William Landsborough in his 1862 search for Burke and Wills, setting off fears that Aboriginal activists were intent on erasing the legacy of white pioneers.

But by 2015, the 150th anniversary of Burketown’s founding, the Century case had been settled by a court-initiated consent order with the state government. Millions of dollars were already flowing from the mine and the state into Aboriginal welfare and development projects. Large parts of Burketown were transferred to native title, including the town square, residential sites and industrial land, and the town now has an alternative Indigenous name, Moungibi.

Outside town, six pastoral leases came under Aboriginal ownership, making the Gangalidda, Garawa and Waanyi the biggest landowners in the shire. Their commercial arm bought out many of the businesses in Burketown, including the pub, the garage, the airport, the tourism centre and the Savannah Lodge.

The Carpentaria Aboriginal Land Council, from where these holdings are administered, is a kind of alternative government to the Burke Shire Council across the street, and the police and other Queensland government agencies.

“Most of Australia’s going to shit but here’s a place you can leave your key in your car, your house unlocked,” says Yanner. “Zero crime rate, no kids on the street, no mischief. No one beating their missus up, no one causing trouble. If they do, we restrict them access to our services and things and kick them out, because basically there’s dozens of people from less functional communities lining up to get in for their kids’ sake to a good community. We don’t do that with any state or government intervention, and deprivation of people’s rights, we do it ourselves: communally, locally. It’s far better than anything the government’s tried elsewhere.”

Doomadgee, to the west, Borroloola further along Highway 1 in the Northern Territory, and Mornington Island out in the Gulf are larger Aboriginal-majority towns notorious for problems of crime, addiction and poor health — and ineffective government interventions to deal with them. “The government doesn’t listen to the people’s ideas, or try out their ideas,” says Yanner. “They’re all concentration camps from the early days.”

He snorts at the idea of getting Aboriginal recruits into the police. “No, we wouldn’t accept it. They’d be the Jacky-Jackies. They’d be a tracker for them. Just like the old days. The only time Aborigines have been with the police is when you need an Aborigine to catch an Aborigine.”

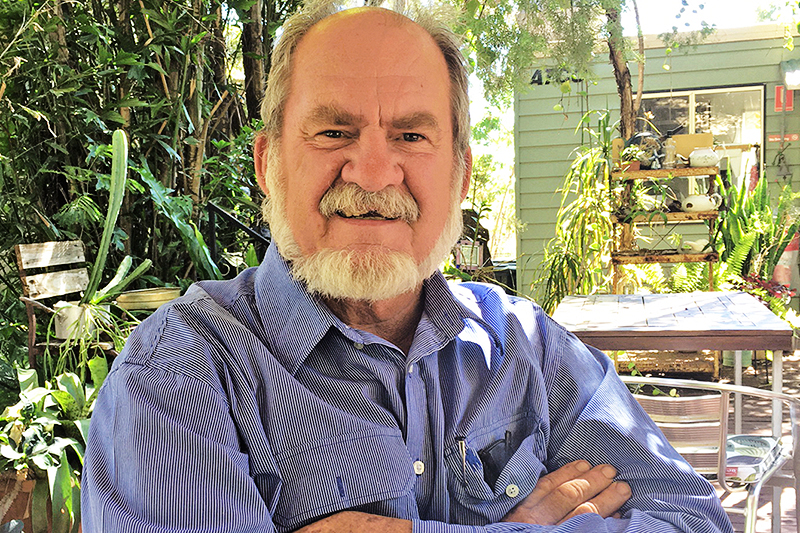

Two of the shire council’s five members are Aboriginal, and a third is of Philippine descent, and Yanner says relations with the council are now cooperative. Ernie Camp, the mayor, concurs and adds to the account of community self-policing. “Sometimes it might be claimed nobody’s doing their parenting, single-parent families, but on the other hand everybody’s doing the parenting,” he says. “Everybody’s keeping an eye out, and certainly not going backwards in giving a shout-out if a kid may or may not be doing the right thing. It becomes community parenting, I suppose.”

Mutual advantage: Burketown’s mayor, Ernie Camp. Hamish McDonald

It’s not a community without problems, though. Youth suicide is a worry, Camp says, with one recent case involving a twelve-year-old, and social media grips young people who might previously have found solace looking after pet animals. Improving year-round road access would help reduce the sense of isolation, he thinks, as well as having national defence, biosecurity and a host of other benefits.

It still gets a bit fraught when, as mayor, Camp has to make a speech on Australia Day. He likes to use the analogy of a vehicle, with both a rear-vision mirror and a windscreen to look forward. “That’s the way life is, you need to have good vision going forward,” he says. “But we need to reflect on the past, and not to do the things again. It should be part of education to look back on history with no restrictions, and tell all.”

With our interview drawing to a close, Camp mentions how, in the midst of the heated negotiations over native title in the late 1990s, he was deeply touched when his three-year-old daughter wandered off from the family homestead and got lost in the bush. Yanner called and offered to bring out all his people in the search. (The little girl was found unharmed after many hours.) Anthropologist Richard Martin tells me that both sides had come to realise they could make native title and reconciliation work to mutual advantage.

The town now follows an annual cycle of tourism and cattle-raising set by the seasons. The three-month wet season, when the town is cut off by floods much of the time, is a wonderful, peaceful interlude, says Camp. “If you want to walk around naked all day you could — nobody’s going to bother you. Not that I’ve ever done it.” Then comes the annual barramundi festival, around Easter, timed so anglers can drive in from outside with the receding of the wet, but not so late into the cooler months that the big fighting fish has gone into semi-hibernation. Skilled fishers can still coax it to strike at the lure.

As the land dries out, it’s time for mustering the cattle. In September comes the unusual long cylindrical cloud formation known as the “morning glory.” Glider pilots fly their high-tech machines up from all over Australia to use Burketown’s airstrip as a base to ride its thermals.

Meanwhile, says Yanner, the Aboriginal peoples of the region keep up their traditions. “We are the only community in Queensland that still runs full tribal initiations here,” he says, holding an imaginary penis in one hand and bringing the other down in a slicing motion. “No painkillers, antibiotics, all that rubbish, no doctors, just the old days and the whole thing proper.”

The young float between the two cultures — among them Yanner’s son Mangubadijarri (“the barramundi jumping out of the water”), who has been studying law and international relations at Bond University on the Gold Coast and is currently managing the Burketown Pub.

One evening towards the end of my visit I took a “sunset cruise” run by the Aboriginal corporation’s tourism office. At the town jetty, I boarded a large, new steel barge and watched crewman Paddy Kunsing haul in a fine fish. Then we set off along the Albert River, the reddening sky reflected in its still waters.

Fish jumped along the shallows. A small crocodile lay on the mud. The crew broke out bottles of wine and beer, and laid out crackers, cheeses, olives and dips. My fellow tourists were eight well-off retirees on a bespoke tour of the Gulf, Cape York and the Torres Strait. Their pilot came along too, and extolled the capabilities of his aircraft, a Pilatus-12 turboprop with luxury seating that could still land on small, remote airfields.

Nevil Shute would certainly have cheered this aviation bit of the Burketown story. Who knows what he would have thought of Tony Abbott and his knighthoods, but I doubt he’d object to the notion of young Brits coming out to work on Australian farms under the proposed free-trade deal with the United Kingdom. And maybe he’d approve of the reconciliation painfully won in a town smaller but more inclusive than the “town like Alice” he envisaged. •