THE BIGGEST star of last week’s Fiber to the Home Conference and Expo, Mike Quigley, was not in Las Vegas. Australia’s National Broadband Network CEO was due to deliver a keynote address but withdrew a couple of weeks earlier while the alternative prime ministers negotiated with country independents about the formation of a minority government. It would not have been a good time for a public employee to spruik the politically controversial plan, especially on The Strip.

Those negotiations went famously well for NBN Co’s plan to build a fibre-to-the-home network to 93 per cent of Australian households and businesses over the next eight years. Tony Windsor, the second-last independent to announce whom he would support, said Labor’s broadband plan was one of the two main issues that eventually made up his mind. The last, Rob Oakeshott, agreed. Labor’s $43 billion NBN whacked the Coalition’s $6 billion broadband plan and with it Tony Abbott’s shot at the prime ministership, at least for now. “You do it once, you do it right and you do it with fibre,” Windsor said, and that’s what Australia is now doing.

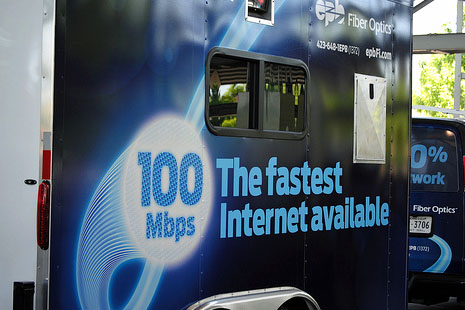

It’s a message that would have gone down well in Las Vegas last week. “All Fiber, All the Way!” was the conference theme. Everyone wanted to do it with fibre. Even without the Australian, there were plenty of people ready to talk. Quigley’s spot was taken by Katie Espeseth, vice-president of fibre optics at EPB, which launched a 1 gigabit-per-second (Gbps) residential broadband service, said to be the United States’ fastest, in Chattanooga the same day the conference opened.

NBN Co was born in the latest global financial crisis. EPB is a child of the last one, the Great Depression. For most of its life, this non-profit agency of the City of Chattanooga has been an electricity distributor. Its first power flowed from the Tennessee Valley Authority in 1939. In the late 1990s, it got into the telecommunications business, and in 2007 Chattanooga City Council approved a plan for a fibre-to-the-home network. The network has now been built past 140,000 of the 170,000 homes EPB serves in greater Chattanooga, the surrounding counties and North Georgia. It will pass the rest of them by the end of the year.

Last week’s announcement of a 1 Gbps symmetrical service – meaning the speed is available for both downloading and uploading – made the front page of the business section of the New York Times. The super-fast service is not cheap – US$350 per month for the top speed (50 Mbps will cost you $140, 15 Mbps $50) – but it’s ten times the download target recommended in the Federal Communications Commission’s National Broadband Plan, released earlier this year.

The FCC proposed a “100 Squared” target – 100 megabits-per-second (Mbps) download speed (50 Mbps for uploading) to 100 million US households (about 90 per cent of the total) by 2020, and 1 Gbps to “anchor institutions” like schools, hospitals and government buildings. 100 Mbps to 90 per cent of households and to business was the target stated in April 2009 for Australia’s fibre NBN. Since then, the government has accepted a recommendation to increase coverage to 93 per cent of premises and Quigley announced during the election campaign that the architecture and technology being deployed would enable 1 Gbps services to individual homes.

There are intense debates in the communications industry around the world about whether these kinds of speeds are necessary for most households now or in the foreseeable future. As you’d expect, there was plenty of enthusiasm for them at the FTTH Conference. EPB won the FTTH Council’s Star Award for “a person, community or company that has gone above and beyond what is expected in the advancement of fiber to the home.” Steve Klein, director of marketing and business development at Allied Telesis, said that most of the all-fibre Requests for Proposals his company was receiving were for 1 Gbps networks. Was this speed needed today for every home for services? No, 100 Mbps was sufficient. But were 1 Gbps networks “economically feasible” today? Yes, he thought.

Ericsson North America’s director of deep fibre access, Fred Terhaar, laid out a “use case” anticipating what a household consuming 120–130 Mbps by 2020 would be doing with all its bandwidth. The residents could be simultaneously using cloud-based 3D gaming (20–40 Mbps), a high-definition video conference (18 Mbps), three high-definition TV channels including one video course lecture (total 45 Mbps), home security (10 Mbps) and “other equipment” (24 mbps). Noting that telcos all around the world are falling short of their targets for homes passed by fibre, he said, “I don’t think the business case for FTTH is a slam dunk.” Working hard to sell its “wave division” fibre technology, Ericsson is also pitching its vision of the global wireless future – “fifty billion connected devices by 2020.”

The overall picture for all-fibre networks in the United States painted by researchers and analysts at the conference was cautious. Mike Render, president of RVA Market Research, which monitors FTTH network construction and take-up for the FTTH Council in North America, released his latest research showing all-fibre networks have now (September 2010) been built past nearly twenty million US homes, 17 per cent of all homes. That figure had increased by 2.7 million over the past twelve months, but it had increased by 4.1 million in the previous year.

Render thought this slowing down was caused by the near-completion of the largest project by the big east coast incumbent Verizon, which has now passed around sixteen million of its planned eighteen million homes, and to delays while many smaller projects have waited for decisions about the allocation of federal “stimulus funds.” The number of “connections,” or subscribers, in the United States grew 11 per cent from 5.8 million in September 2009 to 6.5 million now. FTTH networks increased their share of the broadband type primarily used at home to 6.1 per cent in 2010, up from 4.8 per cent in 2009. DSL and cable still have much bigger shares and, as in Australia, wireless broadband has grown fast – accounting for 13.4 per cent of households’ primary broadband in 2010, up from 11.9 per cent.

According to Roland Montagne, director of the Telecoms Business Unit at European consulting firm IDATE, three-quarters of the world’s 63 million fibre subscribers at the end of 2009 were in Asia, especially Japan and Korea. Many of these are residents in high-rise apartments with fibre-to-the-building (FTTB) networks – the final link inside the building from the fibre access point to the customer’s apartment is still copper, so they are not strictly fibre-all-the-way. It is a similar story in Europe, where over half the 7.7 million “fibre” subscribers are on FTTB networks.

WHY are all-fibre networks being built? In North America, different kinds of organisations are doing it for different reasons. Pure commerce – a direct expectation of increased profits – is not the only one and often not the most important.

Incumbent telcos are doing it to make money but their strategy is mainly defensive. They are trying to resist the drift of customers who don’t care about fixed-line telephones anymore and can get faster broadband speeds from cable operators or more convenience from mobile broadband. Verizon has signed up more than three million subscribers from the sixteen million homes it has passed so far, but is adding them more slowly – 174,000 in the second quarter of this year, down from 300,000 in the same period a year ago. It won’t extend the FTTH network to all its customers at present, even in big cities like Baltimore and downtown Boston, and has no public plan to shut down its copper network and migrate all the traffic to fibre as is now planned in Australia under the agreement-in-principle between Telstra and NBN Co.

Further north, in the Atlantic states of Canada, regional incumbent Bell Aliant is spending half a billion dollars to take fibre past 600,000 homes in its territories by 2012. Its biggest city is Halifax, with a population of around 370,000 people. According to chief technology officer Ivan Toner, the company is building FTTH because it delivers more bandwidth to customers, reduces the complexity and operating costs of the company’s networks and allows it to “leverage its unique cost characteristics.” Getting the green light for the investment from the company’s board was “more about the business case than the technology.”

Power utilities are doing it partly because they think an advanced communications network will help them improve the reliability of their electricity distribution network and assist their customers to monitor and reduce power usage. EPB in Chattanooga got US$111 million from the federal Department of Energy to get its “smart grid” built in two years rather than five. It will offer its customers an Energy Channel that they can watch to see how much energy they are using and what it’s costing.

Other “muni’s” – municipal bodies like local councils – are doing it because they are public bodies with public charters that think fibre is a good idea. IDATE’s Montagne says local authorities were the FTTH pioneers in the United States. In Europe, more than half the 249 fibre access projects in place or under way are being built by power utilities and municipalities. (The state-owned electricity distributor Aurora is heavily involved in the NBN in Tasmania.) Municipalities want all-fibre networks to stimulate the local economy, to enable them to offer innovative online services like health and education, and to ensure the fixed-line telecoms network of the future is run for community rather than financial purposes. If fibre seems a good idea and incumbent telcos are not building it, muni’s will step in.

They are also the most likely to be establishing the kind of wholesale-only, “open access” network that Australia’s fibre NBN will be. This means the network is built and operated by an entity that doesn’t offer retail services. Mike Render’s annual study of FTTH in the United States found take-up rates significantly lower for “muni wholesale” networks (25 per cent of homes passed) than for “muni retail” networks (42 per cent of homes passed) like EPB in Chattanooga, whose customers can take internet, TV and phone service direct from the company building the network. Overall, Render found a take-rate of 36.4 per cent of homes passed by all-fibre networks. The big companies with the big fibre plans, like Verizon and AT&T, have lower than average take rates (31.0 per cent). Smaller telcos building smaller networks are doing much better (49.0 per cent).

Render suggested two related problems that “muni wholesale” networks have had. First, because of their public mandates, they have been reluctant to market themselves aggressively, believing this is the job of the service providers that buy wholesale capacity on their networks and deal direct with retail customers. Second, this has left them dependent on the quality of the service providers they attract. Because they have “no skin in the game” like the infrastructure owner/operator, they have not always been great marketers of everything FTTH can offer. But he says they have been improving over time and thinks the wholesale networks might eventually get better take rates than the retail ones because of the level of service competition that might develop. Once established, a critical mass of service providers on the open-access fibre should make customers reluctant to shift back to another network. Customers who can easily switch retail service providers might stay loyal to fibre.

An example is Utopia, a wholesale network owned by sixteen cities in Utah, which was one of the FTTH pioneers in 2000. Vice president of marketing solutions and operations, Chris Hogan, says the network has been turned around over the last two years. Then, there were just two service providers on the network, now there are seventeen, many home-grown. Four of them offer video, “our crowning achievement.” The incumbent telcos, however, are not among them. Hogan thinks, “There’ll be a day when they come on board but I don’t expect it any time soon.” Verizon’s manager of engineering process assurance, Kevin Smith, concurred. “We don’t share infrastructure.” Could he ever imagine Verizon going onto someone else’s open-access network? “I’d never say never. But we like to control everything we do from start to finish.”

Alongside these examples, Australia’s public wholesale network plan is now unusual because the incumbent is “in.” As a result of the in-principle agreement between NBN Co and Telstra, NBN Co will be able to use Telstra’s ducts and poles, reducing the cost of stringing the fibre (though paying $5 billion for the privilege). It will also get Telstra’s fixed-line traffic shifted across to NBN’s fibre network progressively as it is built in different parts of the country (it’s paying $4 billion for this). In the United States, the incumbents are either building fibre themselves and keeping others off it or, as in Utah, staying away from the wholesale networks being built by others. Telstra is being paid a handsome price for its cooperation, but it means it is in a very different position from vertically integrated North American counterparts like Verizon and Bell Aliant.

Over the last year or so, two factors – the government and Google – have provided some extra motivation to fibre aspirants in the United States. The 2009 American Reinvestment and Recovery Act allocated US$7.2 billion to expand broadband access and adoption in communities across the country. In the second round of funding announced in August, US$1.8 billion was awarded to ninety-four projects. Some residential all-fibre access networks received awards but many more were for “middle mile” (backhaul) projects, “anchor institution projects” delivering fast broadband to educational, healthcare, government and other public institutions, and wireless “last mile” networks in rural areas. The FCC’s National Broadband Plan also proposes other funding initiatives, including shifting up to a further US$15.5 billion over the next decade from the existing Universal Service Fund program to support broadband. “If Congress wishes to accelerate the deployment of broadband to unserved areas and otherwise smooth the transition of the Fund, it could make available public funds of a few billion dollars per year over two to three years.”

In February, Google announced it would build and test 1 Gbps fibre networks in a small number of locations across the United States reaching between 50,000 and 500,000 people. It received over 1000 responses but is yet to announce a decision on the successful communities.

Even with subsidies, this is a tough time to be thinking of making a major investment in a new fixed-line telecoms network. Unemployment in the United States is running at nearly 10 per cent and the most optimistic growth forecasts won’t put much of a dent in that. The old telecommunications cash cow, fixed-line voice telephony, is collapsing, mobile broadband is surging. “It has not been the easiest year of our business lives,” conceded FTTH conference chair, Michael Hill.

Those who are going ahead with all-fibre networks in this climate need a lot of spirit as well as a plausible business case. Accepting the Chairman’s Award at the FTTH Conference for “an individual or company that has shown tremendous effort to promote, educate or accelerate fiber,” the CEO of Hiawatha Broadband Communications in Winona, Minnesota, Gary Evans, said that you do it because “you care deeply about making sure that rural America is not disadvantaged in the new age of connectivity.”

JUST ALONG The Strip from the Fibre to the Home Conference and Expo venue, the Sydney band Human Nature has had a gig at the Imperial Palace six nights a week for a year. They’ve just signed on for another two. Having sung a verse of the national anthem at the Sydney Olympics Opening Ceremony and supported Michael Jackson and Celine Dion tours, the four blokes from Hurlstone Agricultural High had already been big for a while. Las Vegas has put them somewhere else.

The show is a “Celebration of Motown,” ninety minutes of My Girl, A.B.C., Stop! In the Name of Love, I Heard it Through the Grapevine and others from the Detroit factory. Tourists file in, worn out after another searing Southern Nevada day, looking like they’d be happy just to sit, listen and enjoy, but they get dragged out of their seats by the music and the moment and the energy of these Australians. It’s The Wiggles for Boomers, full of folksy growing-up-in-Sydney patter, a crafted mix of self-deprecation and In-Case-You-Hadn’t-Heard-Of-Us self-promotion, and the fabulous harmonies that got them started. Respectful of the legends like Smoky Robinson who’ve supported them, the stars whose hits make up the show and a tight band, they rotate the focus around all four singers, crank up to an encore then bounce out to the merch desk to sell CDs, sign programs and be thoroughly nice to everyone. The Las Vegas Review-Journal awarded them the tag of Number One Best Singers in Las Vegas.

Australians don’t often get to tell the biggest story, especially in Las Vegas. Had Mike Quigley been in town last week, that would have been his gig, because Australia’s NBN, by several country miles, is the big daddy of public broadband plans around the world. Obama’s US$7 billion, Singapore’s and New Zealand’s half a billion or so US dollars each, €2 billion in Greece and France… by these standards even Tony Abbott’s cut-price A$6 billion is big.

Late in life, the nineteenth-century American merchant in Richard Powers’s novel Gain, Jephthah Clare, tried to interest financiers in “visionary risks that made the Lord of All Creation seem a mere jobber.” In his prime, he had done it all. Once he took a chance shipping ice to yellow-fever-addled Martinique, taking on the trade “simply because all his fellow merchants considered it mad. Whatever the mind of man stood unanimous against probably had some merit in it.”

No one is doing fibre quite like Australia. A national plan for a huge territory, fibre to almost all premises, a publicly owned network, wholesale-only but with the incumbent, in principle, now inside the tent. This is structural novelty, cash and ambition on a grand scale.

Do it once? Do it right? We Australians have plenty to do. •