A Territory Story

Northern Territory Library | Until 19 July 2025

A Territory Story begins under the arms of an inviting tree — a banyan tree — albeit one made of modern-day plastic. This species of fig has thick, glossy foliage and a wide, inviting span, and grows around the Top End. Banyans have been places of meeting, refuge and play for millennia, and they are the emblem of the Northern Territory Library, where the exhibition is showing.

For the Larrakia, the traditional owners of the Darwin region, the banyan is known as galamarrma. It offers shade as well as edible fruits and those long fibrous roots — the sort that sprout from branches and search for the ground — that can be turned into string used as fishing lines or intricately woven to create dilly bags, baskets, armbands and art. A famous banyan (below) still stands near Darwin’s council chambers, where it has served as a postal address, a place for meetings and union rallies, and a trading spot for Chinese hawkers. Astonishingly, it has survived every cyclone that Darwin can remember.

“The Tree of Knowledge” (c. 1937): This banyan tree in Darwin’s Cavenagh Street has long been a meeting and trading spot. Northern Territory Library, Yvonne Beames Collection

A Territory Story took three years to conceive and curate. Like so many recent exhibitions, it uses audio, video and interactive features to immerse visitors in the Territory’s sounds and sights. You can hop aboard a mock tourist bus — one of the many used by visitors to explore the Red Centre as transport changed from camels to automobiles — in which an early black-and-white film of one of these ventures is screening. You can choose which trailer of which film set in the Northern Territory you would like to view, or which historic voice — male, female, Indigenous or Chinese — you would like to hear.

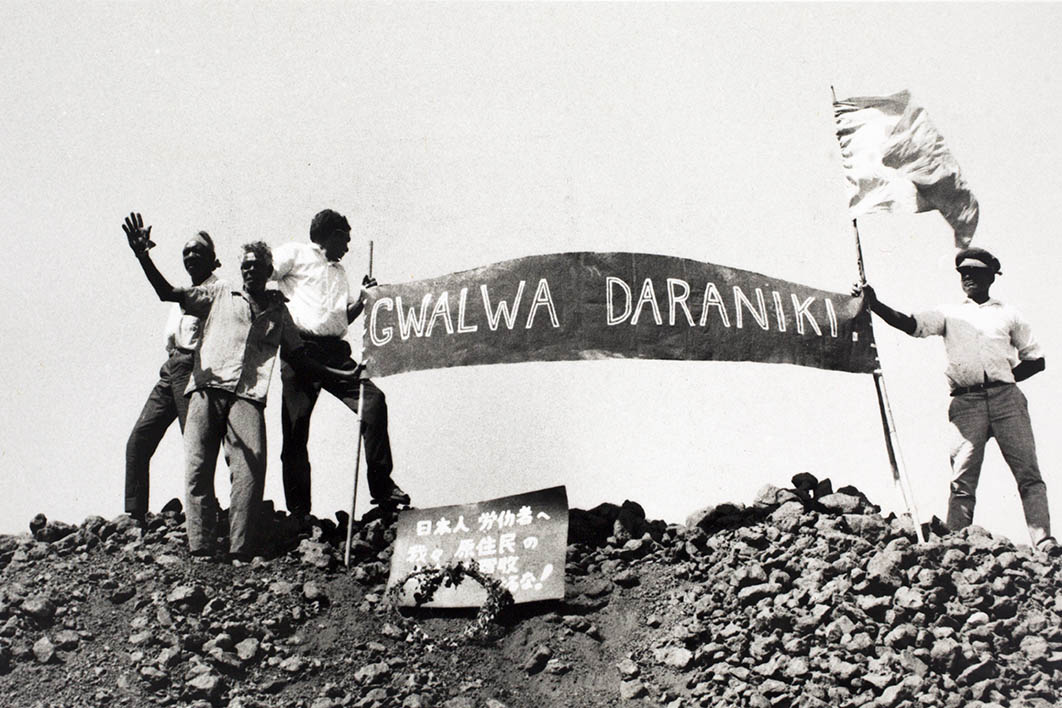

The world of the Larrakia people is foregrounded at the opening, and the beautiful and iconic weaving by Pintupi artists features in stunning variety. The settlers’ “opening up” of the north and centre is here, as are early stockmen and police, the legacies of the removal of Aboriginal children, the often bizarre and iconic front pages of the Northern Territory News (a paper that really celebrates Top End difference), and the impact of the alternating wet and dry seasons. The last third of the exhibition explores films, music and books set in the Territory, from We of the Never Never (1908) and Jedda (1955) to Yothu Yindi’s “Treaty” (1991) and Samson and Delilah (2009). It finishes with a timeline that includes the Dutch navigation of the north coast of Australia, Macassan traders fishing for the knobbly sea cucumbers known as trepang, the spread of mission stations, the opening of railway lines and the first schools, the Coniston Massacre of 1928 (the last documented Australian massacre), and key moments in the land rights movement. The last year displayed, 1977, sees the arrival of Vietnamese refugees.

Put that way, it might sound like another worthy and rather provincial exhibition. But in the weighting of its content, A Territory Story is actually tremendously exciting. Its vision in many ways renders the “history wars” passé.

Early on in the exhibition, for instance, you can touch a screen and see maps showing the major post-contact infrastructure works in the Territory, starting with railway lines and the Overland Telegraph Line from Port Augusta to Darwin in the 1870s. Next to this, on another screen, you can explore the longer history of the Northern Territory, beginning with the arrival of Aboriginal people in the Top End and taking in their trading routes, language and songlines. Here you can learn about sites of conflict, missions, and the places where land rights claims have been successful.

“Dugout canoe, Daly River” (c. 1935): Coastal Aboriginal people readily adopted the dugout canoe design brought to northern Australia by Macassan trepang fishers. Northern Territory Library, Charles Barrett Collection

In another section, the magnificent and varied photographic collection of the library is brilliantly put to work. A fascinating array of exhibits is accompanied by detailed explanations of how Territorians built houses sufficiently suited to the climate, and how architecture changed after Cyclone Tracy in 1974. You can also discover how Aboriginal people made shelters just right their purposes — whether travelling, hunting or at ceremony — that also suited different seasons, weather and locations: windbreaks for cold desert winds; paperbark and stringybark roofs to keep out the rain.

One of the more extraordinary stories comes early in the exhibition. Speaking of the violence and lawlessness that so often followed pastoralists in this part of the country from the 1870s onwards, this section details how uneasy relationships nonetheless began to build. When thefts at a fencer’s hut were reported in 1911, mounted constable Bill Johns went to investigate and arrested four Aboriginal men. As was standard in the Northern Territory at the time — but soon became an anachronism — neck chains were used on the prisoners. When the constable was swept away by the current of a swollen, fast-moving river (his horse had lost its footing), one of these men, whose name was Ayaiga, or Neighbour, dived in and saved him. Later, Ayaiga was not only acquitted of theft for lack of evidence at the trial but also awarded the highest honour for civilian gallantry by King George V. (Replicas of this medal are held by the NT Library and by Ayaiga’s descendants, with the original at the National Library of Australia.)

This is what reconciliation looks like, and there is not a whiff of tokenism. This is an exhibition about people, like the proud descendants of Ayaiga, and like those removed and their descendants. This focus is particularly striking when the exhibition looks at the stolen generations, detailing the policies and perceptions of the time while allowing visitors to listen to interviews with those who were themselves removed, or their descendants. If nations, states and territories are unified not only as administrative units but also as imagined places, the Northern Territory constructed in this exhibition is a full and richly textured one that encompasses its many experiences.

It is not simply a feel-good, postcolonial political point but what the Northern Territory has become. If you wander through Parliament House, the building in which the library is housed, it is clear how many Indigenous people are members of its Legislative Assembly — a huge difference from the makeup of federal parliament. And as a placard makes clear, they are prominent businesspeople, sportspeople, and so on.

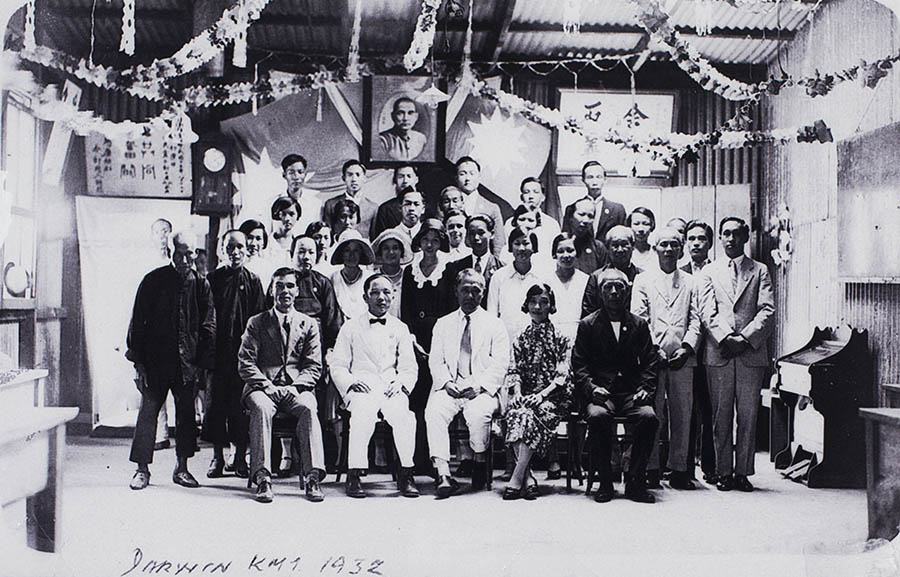

“Kuo Min Tang Party, Darwin Branch” (1932): Darwin’s branch of Kuomintang poses in front of a portrait of their leader, General Chiang Kai-shek. Northern Territory Library, Chan Collection

This is not insignificant given the polarisation that has afflicted national discussions of Australian history for decades. It was in 1996, under prime minister John Howard, that talk of the “balance sheet” of history began: in November of that year he said that “our history is one of heroic achievement and… we have achieved much more as a nation of which we can be proud than of which we should be ashamed.” This increasingly intense debate culminated in the history wars of the early 2000s and continues today in debates about statues of Captain Cook and more.

Political change was in the air when Kevin Rudd delivered an apology on behalf of the Australian government to the stolen generations in 2007. And yet, as many have recognised, this apology, while significant and overdue, was also limited. As historian Catherine Kevin noted, it was an apology that was willing to recognise child removal and the sexual exploitation of women but shied away from other gritty realities of Australian colonialism, like dispossession and pressing matters of sovereignty.

What makes this exhibition different, then, is that the violence of colonialism is recognised — though it does not form the focus — while the exhibition remains generally positive. That the key library of the Northern Territory, a government-funded library, could produce such a balanced and enthralling exhibition is extraordinary and cheering.

Greg Johns’s sculpture, Monument to Mulga Bill and Neighbour (2010). Northern Territory Library

Of course, the Northern Territory, and perhaps Darwin in particular, takes pride in being different. As one of the exhibition placards reads, it is the home of “the stayers, the tourists, the new chums, the blow-ins, the eccentrics, the hermits, the escapees.” By this it means more than the white settlers and Afghan cameleers who appeared in the 1870s. It’s talking about the Chinese who came in the 1880s, the Japanese, Malays and Filipinos who came to dive for pearl shell, the Greek and Italian refugees who came after the second world war, and the Vietnamese who began arriving in the 1970s. This is the Northern Territory as an exciting cultural melting pot with Darwin as its metropolitan, gentrifying and self-confident hub. Yet many Indigenous groups are insistently present too, their ongoing culture engaged with in a rich, interwoven way as a large part of the social fabric of the Northern Territory.

Darwin’s many and pressing complexities are highly visible, of course. Located in the CBD, A Territory Story seems to recognise, even if only implicitly, just how much unfinished business there is. At the entrance is Greg Johns’s sculpture, Monument to Mulga Bill and Neighbour, which depicts Ayaiga’s rescue of the constable. The final links of Ayaiga’s chain are free of rust and he reaches out an ochre-blown hand, suggestive of friendship and assistance. Here is a hint of where hope lies — in the recognition of an entangled past and in respectful relationships in the present. •