A letter from a prime minister, a gumleaf, a child’s notebook, a coveted sporting trophy: what do these things have in common? On the surface, not much at all. But for Tony Armstrong’s Extra-Ordinary Things, that doesn’t matter in the slightest.

In fact, the more unusual, eclectic and seemingly mundane the better. Because in this five-part ABC TV series and accompanying exhibition at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra/Kamberri (on display until 13 October this year), it isn’t really the objects in and of themselves that are important; it’s the stories and the people behind them that together weave a story about the nation and its past.

This project sees popular television presenter and guest curator Tony Armstrong travel the country in search of items for his special exhibition. From metropolitan centres to the remotest of towns, he seeks out objects that shed light on Australia and Australians from a whole range of perspectives. Rather than historically significant objects, he’s interested in things that normally wouldn’t be viewed as anything special: “stuff,” “junk,” “crap,” as he puts it. Each extra-ordinary thing he collects is considered equally important as the next.

Guided by the National Museum’s expert curators, Armstrong shows viewers the powerful storytelling potential held in personal items, whether they have been treasured for generations or tucked away and forgotten in the back of a closet. As head curator, Sophie Jensen, sums up in episode one: “Objects don’t tell stories. People tell stories. But so often, the object provides the anchor through which a story can be told.”

Some of the objects that have made their way into the exhibition capture major moments in Australian history. The iconic anti-Iraq war protest that saw the words NO WAR painted on the sails of the Sydney Opera House in 2003 is represented by the paint tray used for the stunt. Another Sydney/Tubowgule icon is the centre of a different history-making moment: the construction of the Harbour Bridge. Via a commemorative pin held by George Manly Killen’s descendants we hear the forgotten story of how one worker selflessly dived into the cold waters of the harbour below to save a friend who had slipped and fallen. Turns out, the ordinary can be rather extra-ordinary.

Protest paint: the tray used to daub NO WAR on the Opera House. National Museum of Australia

Natural disaster is a prominent theme, with significant events — Cyclone Tracy, the Ash Wednesday bushfires, the Lismore floods of 2022 — coming to the fore. But unusually, these historic moments are represented through stories that allow us to see them as moments in people’s longer, multifaceted lives.

A household trunk at once reveals the sheer terror of being enveloped in one of Darwin’s worst cyclones and a mother’s strength in saving her infant son. Adding a very human dimension to the tragedy of bushfire, a signet ring worn by a firefighter taken by the flames also shows how a family can foster intergenerational care for community and the natural landscape. And a handmade knitted blanket using all the colours of the rainbow survived a regional town’s worst floods on record to remind us how far we have come in accepting queer lives and love.

This mix of seemingly humble items liberates the project from following standard accounts of milestones in Australia’s past. Just as the series jumps around time and space, the exhibition at the National Museum follows a non-linear structure that emphasises the diverse people and experiences that make up Australian history. Cleverly recreating the series’ television set, physically centred around a signpost pointing to the twenty-two filming locations, visitors feel like they have entered the series itself. The multimedia nature of the project is united here, with video clips playing around the dark room alongside the glass cabinets containing these extra-ordinary things.

Each episode, and therefore each section of the exhibition space, highlights the experiences of First Nations peoples. This is made all the more powerful by Armstrong’s involvement as a Barranbinya man. The use of dual English and Indigenous language names for each location is just one signal of a move to more sustained recognition of this continent’s past and many cultures.

In Perth/Boorloo Armstrong meets eleven-year-old Inkabee and his father Flewnt, both Noongar Wongi rappers. Young Inkabee’s first lyric book is among the newer items on display, but the show contextualises his music-making within a long history of Aboriginal protest song, pioneered by musicians such as Archie Roach and Yothu Yindi. This father and son duo obliterate negative stereotypes of First Nations men and masculinity, something that stayed with Armstrong long after filming.

In Redfern/Gunnyana Armstrong meets twenty-one-year-old Marissa (Riss) Williamson Pohlman, a Ngarrindjeri woman who in 2023 became the first woman to win the Arthur Tunstall best boxer trophy. Archival footage of Tunstall seamlessly supports Riss’s characterisation of Tunstall’s views as racist and misogynist. Her triumph juxtaposes perfectly with the award’s namesake and drives home how we as a society have the ability to change the path we are on. A survivor of homelessness and mental health struggles, she is now off to the Paris Olympics (go Riss!).

The series’ five episodes were aired on the ABC in the weeks leading up to the exhibition’s launch, a special event that saw the National Museum’s atrium filled with eager visitors on a cold and drizzly night in the capital. Earlier that day I asked Armstrong what drew him to the project. He explained the context out of which it emerged, especially the social divisions and struggles highlighted by horrific summer bushfires, the Covid pandemic, and the Black Lives Matter movement.

Though Australia has “a chequered history,” he feels it is important to share tales that together make up the “heartbeat of Australia.” Inkabee, Riss, and the other Indigenous participants demonstrate the kind of “strength-based stories” that Armstrong told me we need now more than ever. As he says during the show, there has “never been a more important time than right now to be representing mob in positive ways.”

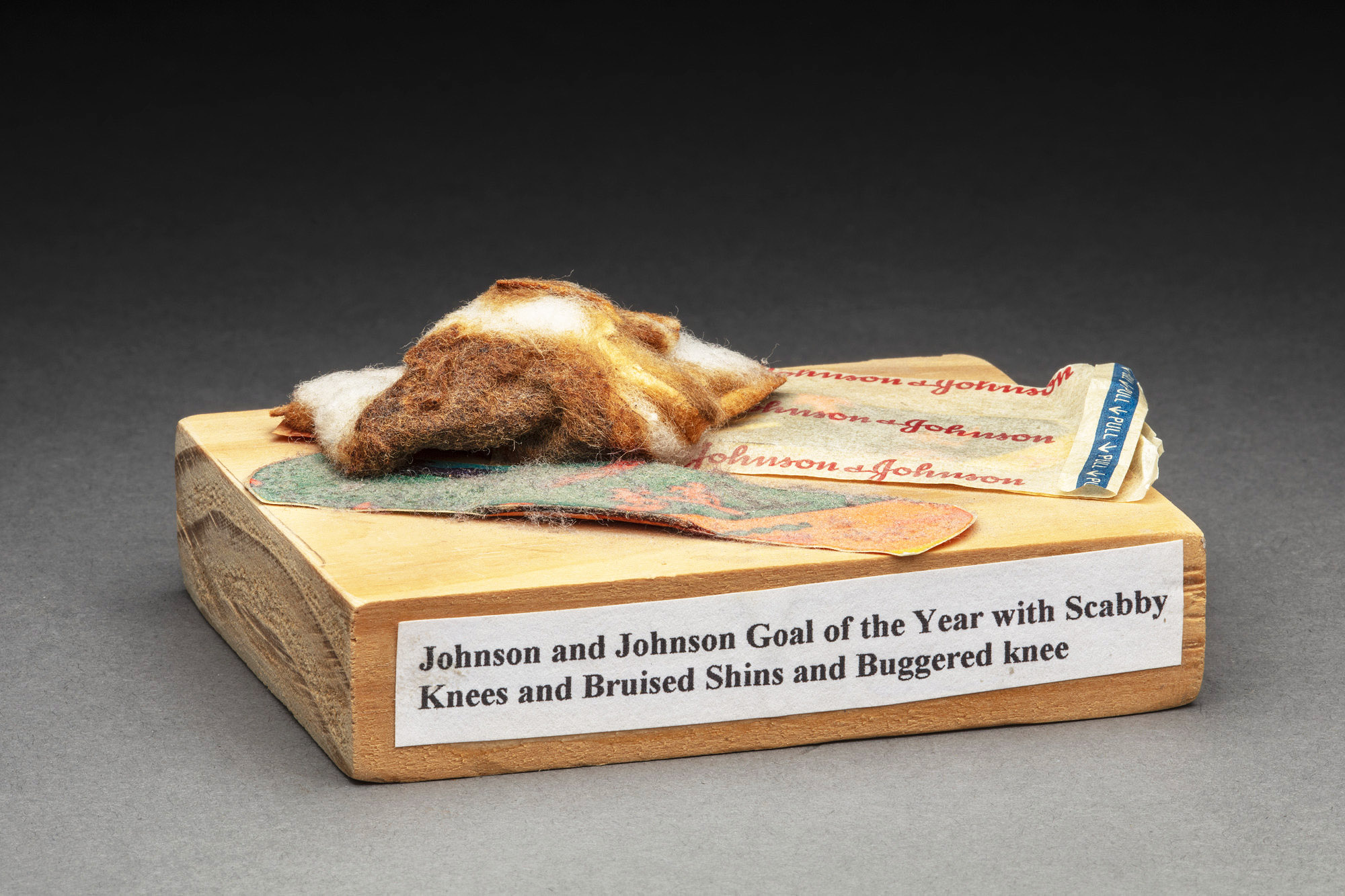

As any good representation of society and culture should, this project draws attention to a wide range of Australians’ experiences. In Adelaide/Tardanya, Armstrong visits the home of Truffy Maginnis, founder of the Adelaide Armpits (1982), a soccer team of openly lesbian players. Her extra-ordinary thing — a trophy for the “Johnson and Johnson Goal of the Year with Scabby Knees and Bruised Shins and Buggered knee [sic],” complete with decorative bandaids and antiseptic-soaked cotton wool — attests to the rich history of community-based activist movements for queer and women’s rights in late twentieth-century Australia. A novelty cheque won by surfer Lucy Small in 2021 that amounted to less than half the men’s prize money shows that we have a long way still to go in the fight for gender equity.

Truffy’s trophy. National Museum of Australia

Migration forms another core theme of the project. The Di Chiera Brothers’ “conti roll” symbolises the postwar immigration story that saw shiploads of Italians make their mark on this country. Vietnamese-born Miranda Chau’s photograph of the day she was one of 290 refugees rescued by an oil tanker in 1978 prompts a sensitive reflection on the consequences of the Vietnam war. Iranian Hamed Allahyari’s Persian zinc plate captures the challenges facing modern-day asylum seekers.

Sometimes light-hearted, sometimes heart-wrenching, Extra-Ordinary Things is largely optimistic in tone. It’s supposed to be. When I asked Armstrong what he hoped the project would achieve, he said: “I hope it gets people telling stories.” Whether you’re asking your nanna or your friends to share their extraordinary things, his advice is to “be inquisitive, be curious.” When I asked curator Craig Middleton the same question, his response similarly centred on encouraging people to reflect on how they apply meaning to things and to recognise the importance of individual stories to our collective narrative.

There is a risk in covering such wide territory that the objects and their stories might be abstracted from their contexts or only scratch the surface of the complex histories to which each speaks. And, of course, with limited time and space, only so much detail can be given.

But this isn’t supposed to be a strict academic exercise, and it doesn’t need to be. The project is optimistic — not a tone we often see in academic analysis — though it still requires its audience to stop, listen, and ask questions. It expertly uses humour and entertainment to convey ideas that the general public might not normally encounter. For some, it likely challenges their ideas about what defines this country. That’s something to be admired, even if the scholarly minded might want more depth and detail. Not all representations of history have to be the same.

This is a prime example of what public history can do. An initiative of the ABC, the National Museum, Fremantle Media, and Screen Australia, it shows what can be achieved when institutions work together (and when funding is allocated to enable this work to happen in the first place). It’s fun. It’s funny. Armstrong’s charismatic personality helps drive the show, and his empathetic engagement with his participants — whether they are a horse race manager from a country town or an acclaimed Indigenous dancer and choreographer — helps invest the audience in the stories being told.

The team from the National Museum are just as wonderful; as Middleton put it, the museum essentially features as a “character in the show,” rather than simply a source of information. He, Jensen, and their curatorial colleague Martha Sear speak with much clarity throughout the series, providing important historical context and explaining material culture concepts in ways that enable viewers to understand why objects matter and what they can reveal. Speaking at the launch event, Sear passionately told the room how, having the “power to hold memories,” objects “do something unique.” They can be shared. Through them, you can travel across time and space; you can even “travel through the human heart.’

Heart and a desire for connection drives the Extra-Ordinary Things project. This doesn’t mean it shies away from the murkier aspects of our past or even our present. In the final episode, Armstrong speaks from the edge of the “exclusion zone” that marked the area in central Perth/Boorloo that First Nations people, only seventy years ago, were not permitted to enter freely.

Overall, though, the project is intended to be uplifting. It’s an example of how storytelling can bridge divides, allow us to confront realities, and enable us to make choices that might go some way to rectifying wrongs. In a time of volatile international conflict, climate crisis, and social inequalities, having faith in the possibility of working towards a better future is perhaps the most extra-ordinary thing of all. •