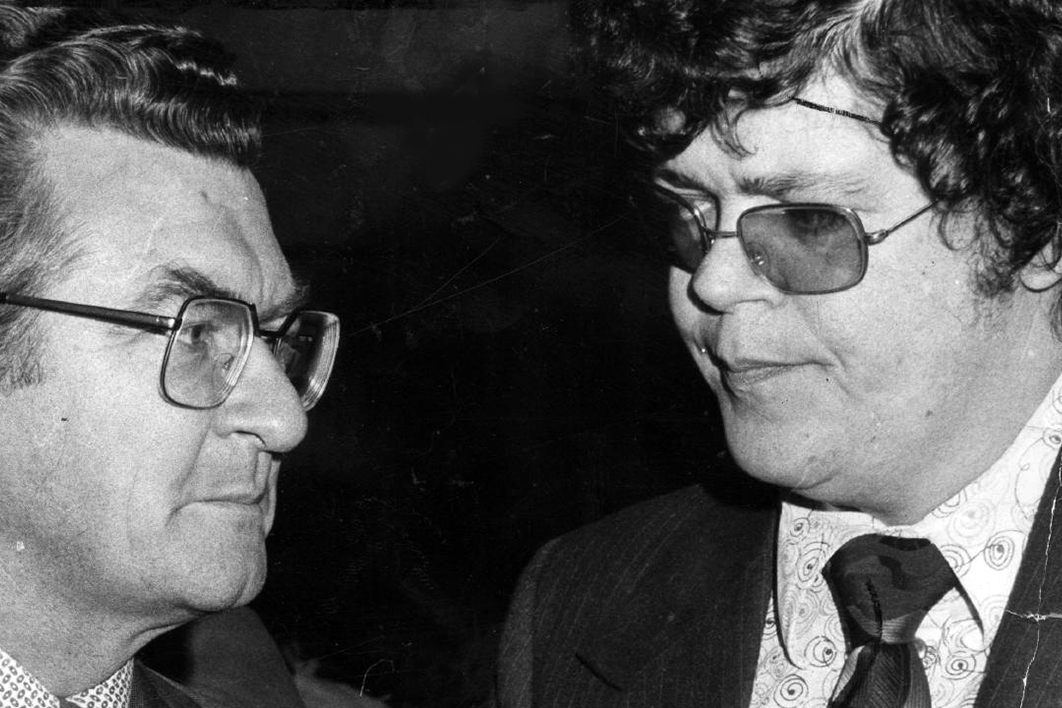

The 1980s should have been David Combe’s time. During an arduous career as a political operative — most recently as Labor Party federal secretary — this stocky, woolly-haired figure had shown exceptional organisational skill and financial acumen in helping bring the party organisation back from the brink. As he did so, he painstakingly built up his political and business networks with an eye to the party’s future — as well as his own.

In 1976 he had loyally taken the political hit — or at least much of its impact — following prime minister Gough Whitlam’s gross miscalculation in consenting to the pursuit of party funding from Iraq. After resigning as party secretary in 1981, he set up as a “government relations consultant” — or lobbyist — and his next goal was to use his old party contacts to make serious money. Although in this respect a man completely in tune with the times, Combe was sadly hampered by one disabling legacy from the past: he could not let go of 1975.

He remained committed to the theory that the Central Intelligence Agency had played a major role in the demise of the Whitlam government, and carried with him an open hostility to the United States on that score. It was an attitude common enough among the Labor left but increasingly played down by the new pragmatists who had taken control of the party. It was an attitude that would cost Combe his career and reputation.

Combe was not yet forty when he fatefully accepted an invitation to dine with a young Russian diplomat named Valery Ivanov on election eve. One business on whose behalf Combe had been working was Commercial Bureau, which had a unique status as the only Australian trading house accredited in the Soviet Union. The company was run by a mysterious businessman named Laurie Matheson; he seemed very rich, which impressed Combe, had a background in naval intelligence, and in due course it would become all too clear that he was also an informer for the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation, if not something more sinister.

Matheson’s main business problem was that his former managing director had left to establish a rival organisation that was providing Commercial Bureau with unwelcome competition. In particular, he was having difficulty in New South Wales, and needed to gain a hearing with the Labor government there. Perhaps Combe might help him? Combe, as a member of the Australia–USSR Friendship Society, was about to travel with his wife to the Soviet Union. He undertook to work on Matheson’s behalf while he was in Moscow.

The first secretary in Canberra’s Soviet embassy responsible for liaison with the Friendship Society was Ivanov, who was only thirty-three when he arrived in Australia in 1981. His youth was one factor that aroused ASIO’s suspicion that he might be an intelligence officer; Soviet diplomats of his seniority would normally be at least in their late thirties. The interest in him grew and, with it, the interest in his connection to David Combe. It would later come to light that Ivanov had organised Combe’s invitation to Moscow. By the time Combe arrived back in Canberra from Moscow late in 1982, ASIO was convinced that Ivanov was a member of the KGB.

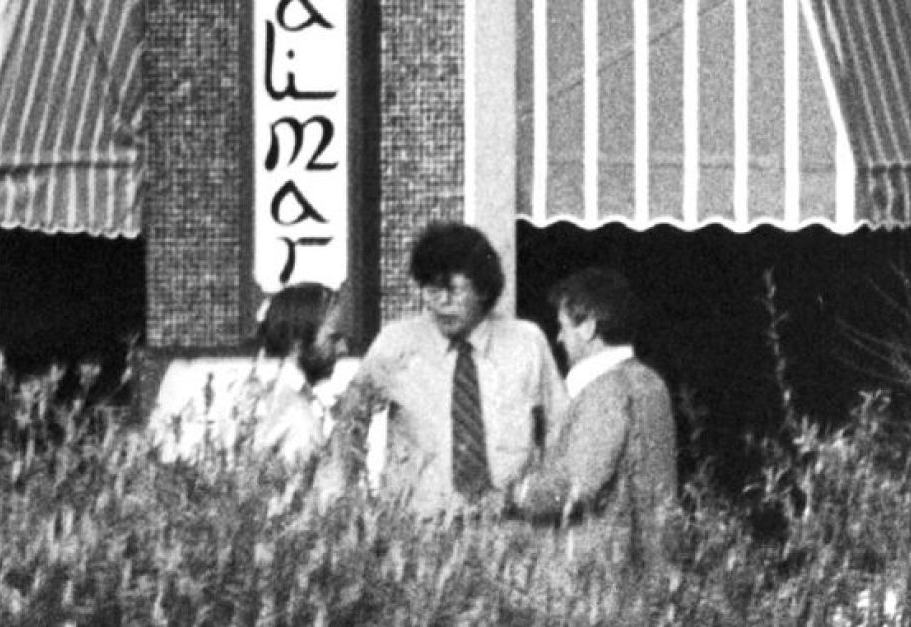

Under surveillance: an undated ASIO photo of David Combe (centre). ASIO

After his return, Combe provided Matheson with a report, based on his consultations with officials in Moscow, on how he could develop his company’s trade with the Soviet Union. Combe pointed out that political tensions between Australia and the Soviet Union were a barrier to trade and recommended that Commercial Bureau might try to ease these tensions by participating in the Australia–USSR Friendship Society. He also suggested an upgrade of relations between the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the Australian Labor Party, to be engineered by none other than David Combe, government relations consultant. Combe billed Matheson for $2500; ASIO soon had copies of both the report and the bill.

As ASIO built its case against Ivanov, it considered approaching Combe to warn him of his predicament; perhaps he could be persuaded to report on his new friend, thereby helping ASIO make its case? That approach was never made, and to this extent the self-serving claims later made by the ASIO director-general, Harvey Barnett, that he had saved Combe “from himself” or from the clutches of the KGB, should not be taken too seriously. In the context of the expulsion of KGB spies from other Western countries during this period, as well as local criticism from both right and left concerning ASIO’s capacity, the organisation needed to catch a spy of its own.

On the evening of 4 March 1983, the night before the election that would bring Bob Hawke and his Labor colleagues to power, Combe arrived at the Canberra home of Ivanov, his wife Vera, and their seven-year-old daughter Irina. Combe had already had plenty to drink; by his own account, he “probably would not have run the gauntlet of a random breath-testing unit” if required to do so on the way to the house. By the time he left — after many hours of food, conversation, vodka, beer, red wine, white wine and liqueur — he was “pretty well gone.” Whether Combe had revealed himself on that evening to be a threat to national security would later be debated passionately. That he was a menace to traffic safety is beyond question.

The conversation during the evening was often rambling and, in Combe’s case, increasingly slurred. He did most of the talking and had great hopes for the future — the country’s and his own — under the Labor government that now seemed an inevitability. “I was going to put in my list of requests on… about Thursday or Friday,” he told Ivanov. “I thought I’d ask to be chairman of Qantas for first choice, and then ambassador to Moscow, something like that you know.”

“Being ambassador to Moscow, David, you’ll keep your hand on the pulse,” replied the homesick diplomat wistfully. After a couple of years of money-making as a lobbyist, Combe explained, “then I’ll say, right, ‘I’m entitled to something, I want my job for the boys, ambassadorship, Moscow will suit me very much.’” Ivanov was confused; who were “the boys”? Combe gave an impromptu lesson in Australian English, explaining that he meant patronage. Combe told Ivanov that he — Combe — was one of “the boys,” and payday had now arrived:

I’m putting myself in a situation where, I’ll level with you because you’re a friend, Valery, I’m going to make the next two years, they’re going to be the two most economically fruitful years of my life. I’ve worked a long while for the Labor movement.… I’ve got nothing for it; in financial terms the next two years with a federal government and four state governments, I’m in enormous demand, I mean I’m in a situation where I can say to Esso, you know, IBM, and all these companies, well, you know, I’ll listen to your proposition and I’ll make a decision in due course whether I’m going to work for you… [I]n the next few weeks they’re the decisions I have to make. Whom do I work for and on what basis, and I’m going to charge very big money… [T]he buggers are going to be paying.

Combe went on to discuss with Ivanov the possibility of working for the Soviet Union to find opportunities for trade in Australia. But he was also representing a particular company with interests in the Soviet trade, Commercial Bureau, and he said that Ivanov would need to decide whether Combe could work for both. Combe eventually thanked his hosts and wandered out into the night. The whole conversation had been recorded by ASIO, which had a listening device installed in the ceiling of the Ivanov home.

Harvey Barnett, a career spy and now the director-general of ASIO, had every reason to wish to start off on a sound footing with Hawke and the new government. A Labor government had established ASIO in the late 1940s, but Labor’s relations with the security agencies had often been fraught in the years since.

David Combe and Valery Ivanov presented Barnett with a useful opportunity, and he picked his mark exceedingly well when he sidestepped his own minister, attorney-general Gareth Evans, and went straight to Hawke. Combe was obviously a hostile witness, but it is hard to disagree with his later assessment that, like the good spy he was, Barnett had “studied his target, assessed his strengths and weaknesses, selected which strings to play upon and which drums to beat.”

Barnett would have known that Hawke, despite the support he had received from the left in his bid to become ACTU president in 1969, had strongly pro-American and equally vigorous anti-communist, and especially anti-Soviet, opinions. As a union leader, he had enjoyed friendly — critics on the left thought rather too friendly — relations with US officialdom in Australia. And in 1979 the Soviet authorities had humiliated Hawke in connection with his fruitless effort to negotiate the passage of Jewish “refuseniks” from the country. Hawke felt double-crossed and claims to have contemplated suicide; he was clearly someone who would be receptive to a strongly anti-Soviet message from the director-general of ASIO.

At a meeting late in the afternoon of 20 April, Barnett told Hawke that ASIO had not only identified a KGB agent but had also uncovered an effort, by that same agent, to turn a former national secretary of the Labor Party into an agent of influence. Central to the case was that ASIO had recorded Ivanov suggesting to Combe that the relationship between them should become clandestine. Barnett also told Hawke about Combe’s “jobs for the boys” boasting and his offer to work for the Soviet Union in commercial matters. Combe, Barnett reported, had expressed bitterly anti-American views, was convinced of the CIA’s role in the dismissal of the Whitlam government and had shown sympathy with the goals of the Soviet Union.

The director-general appears to have been in no great hurry to let the government know what his spies had found, and many weeks had passed since the fateful 4 March dinner. Yet on hearing Barnett’s story, Hawke determined that the government needed to move quickly. He and Barnett discussed three possibilities: Combe could be called in for a talk — or, to put it in Hawke’s later words to the royal commission on the affair, “I could call Mr Combe in and carpet him.” Hawke and Barnett saw several problems with this option: Combe, for instance, might talk to Ivanov; or once the news got out, the government might be seen to have compromised Australian security by giving special treatment to one of its own.

A second possibility was that Ivanov could be quietly expelled, and that was quickly dismissed as well. Instead, a public expulsion would occur, an option that Barnett plainly admitted would suit ASIO in view of the favourable publicity it would inevitably generate.

Hawke saw benefits for his government beyond sending out the right message about its commitment to national security: he had just returned from his government’s economic summit with business and the unions, an occasion intended to underline the government’s willingness to deal openly and fairly with anyone committed to solving the nation’s problems. The perception that a former senior party official was working hard behind the scenes, exploiting his connections on behalf of favoured clients, would have inconveniently undermined this central message. Hawke clearly recognised the danger of having Combe on the loose, selling access to the government, or even being seen as capable of doing so.

Cabinet’s national and international security subcommittee was quickly convened that evening, with all but two members present. Barnett briefed members, and made the case against Combe in particular seem damning. Hawke gave his full support to that version of events, and ministers were not permitted to see the transcript of the crucial 4 March dinner. Bill Hayden, now foreign minister, told the royal commission that “we left concluding that something very nasty and sinister and improper had been concluded or was about to be concluded between Combe and Ivanov.” As they left the room, Hayden said to another minister, Mick Young, that he would never have thought Combe capable of spying against his own country. “I was quite distressed,” Hayden recalled, and he thought Young, who as a fellow South Australian was even closer to Combe, “was equally upset.”

But as Hayden later told the royal commission, once ASIO officials started reading selections from the transcripts to ministers the following day, “the whole thing started to fall apart very quickly… the very sinister connotations which had been put to us did not stand up.” He could see nothing in the 4 March conversation other than a lobbyist doing his job or, at worst, a greedy man seeking to enrich himself through a commercial arrangement. Ministers did not like what they saw; but Combe’s actions, so far as they could see, made him neither traitor nor potential traitor.

The security subcommittee, however, decided that Ivanov should be expelled and Combe placed under surveillance. The former Labor national secretary’s phones were tapped. On 22 April Hayden called in the Soviet ambassador and told him Ivanov had a week to leave the country; four days later, a cabinet meeting in Adelaide decided to cut off Combe’s access to ministers in his capacity as a lobbyist. The government had destroyed Combe’s livelihood; the prime minister even went to the trouble of calling two men with whom Combe was about to go into business to warn them off doing so.

With so many messages being sent here and there, Canberra was awash with rumours. On 8 May the Sunday Telegraph carried the journalist Laurie Oakes’s claim that “a member of the prime minister’s own party” who knew Ivanov had, as a result of a recent government decision, been frozen out of contact with ministers. Paul Kelly revealed in the Sydney Morning Herald on 10 May that ASIO had been watching the activities of a “senior Labor man” who was “one of the most important and influential figures in the party over the past two decades.” The security service had told the government he was “a potential security risk”; the Labor man was “determined to clear his name” and intended presenting Hawke with a document setting out his case.

It is a measure of the suspicion ASIO still aroused within the Labor Party that at the caucus meeting held that morning, Tom Uren, a left-wing government minister who had also been a member of the Whitlam government, asked Hawke whether he — Uren — was the figure being referred to in Kelly’s story.

The opposition was also asking questions in parliament that afternoon: three in the space of a few minutes. It was the third question, posed by National Party heavyweight Ian Sinclair, that let the cat out of the bag; he asked whether members of the government had been instructed to dissociate themselves from David Combe, naming him for the first time. That afternoon, in a sensational front-page story headed “Russian Spy: Labor Official Named,” Sydney’s Daily Mirror claimed that a senior Labor official had “been named a Soviet spy by Australia’s security forces.” No one could now fail to associate the gathering rumours with Combe.

When members of the government saw this article, they were unsure whether to laugh or cry. It was an outrageous libel and, at a time when cold war conflict was still central to international affairs, a deeply damaging accusation. Combe was effectively being called a traitor. Yet the article ironically offered a way out for everyone, since if Combe decided to sue he would surely be the recipient of a massive windfall.

The following day, the government issued a ministerial statement declaring that “Combe’s relationship with Ivanov had developed to the point that it gave rise to serious security concern” of a degree that made it inappropriate for the government to deal with him in his capacity as lobbyist. Combe, Hawke reported, “understands and accepts” this decision. (Conversations had been going on behind the scenes with Combe as the government sought to contain the damage.) Combe, Hawke hastened to add, had committed no criminal offence, nor was there any foundation for the allegation that he was “in any sense a Soviet spy.”

Combe could take little consolation from this statement, except that it potentially strengthened his case for a libel suit against the Mirror. But he was out of business, he and his family were besieged by the media, and he would soon be widely portrayed “as some sort of buffoon.” The story of the family’s not inconsiderable suffering is related in an account by Combe’s wife, Meena Blesing, who reported that her husband “was psychologically destroyed and could not face the ruin of his life. The family disintegrated.”

Combe’s sons suffered schoolyard taunts about their father the communist spy, and the media laid siege to their Canberra home. The Combes felt shunned and even betrayed by old friends, while the government’s decision to call a royal commission under Justice Robert Hope, who had inquired into the intelligence services on the initiative of the Whitlam government in the mid 1970s, only prolonged the family’s agony. It was an exercise designed to vindicate the government’s actions in the affair, which it did, ably assisted by a three-day appearance in the witness box by the prime minister himself. Combe, meanwhile, used his many contacts in the party and the media to arouse sympathy for his plight and attract a measure of support.

Eventually there was a rehabilitation of sorts. The government feared the book that Combe was writing about his treatment. The Labor left, increasingly angry over a range of government policies, was also threatening to make an issue of the affair — if necessary, on the floor of the national conference in 1984. Combe himself appeared regularly in the media and at public events to give his side of the story and attack the government.

So the party effectively brought Combe back into the fold. Hawke even spoke at the conference, reiterating that he had acted in defence of the national interest rather than out of any animus, and emphasising that there was now “no blackball against David Combe.” In 1985 Combe would be sent to western Canada as trade commissioner; another government overseas appointment followed in the early 1990s. He would eventually make a successful career in the private sector, as an executive in the wine industry.

Combe had behaved unwisely in many ways, but his desire to build a lucrative career for himself after many years of loyal party service was understandable. His mistake was to boast about it in a manner that rubbed the noses of senior members of the government — indeed, even the nose of the prime minister himself — in the money he was making or about to make on the back of his party connections. Yet in this respect Combe exemplified the spirit of the era that was opening up. There was money to be made, and he wanted to be in on the act. His weakness was that he also remained preoccupied with fighting the battles of the 1960s and 1970s — especially those of 1975 — and underestimated the continuing power of the cold war to generate fear and loathing.

Barnett and ASIO, for their part, held a fanciful and self-serving view of the influence Combe was likely to be able to wield under a Labor government. It is true that Combe was well connected and certainly well placed to work as a lobbyist, but Barnett’s later suggestions concerning his likely clout were comically far-fetched. The case apparently showed the KGB’s ability and taste for targeting “the top echelon of Australian opinion-formers” and its desire for “some degree of rapprochement” between the Labor Party and the Soviet Communist Party — all, according to Barnett, with the aim of “neutering” social democratic parties so that, “when any crunch came,” they would be “quiescent in the face of Soviet power.”

Combe, claimed Barnett, “was within a hair’s breadth of entering the grand gallery of KGB spies, along with Philby, Burgess, Maclean, Fuchs, Blunt… I like to think I saved him from such a fate.” Kim Philby had been a senior MI6 officer while spying for Moscow, yet it is notable that not even the royal commission was able to identify what kind of material a lobbyist such as Combe, even if he had been inclined to do so, would have been able to pass on to the Russians.

The reputation of the intelligence agencies suffered further damage when in late November 1983, ASIS — Australia’s overseas intelligence service — conducted a training exercise that went embarrassingly wrong at the Sheraton Hotel in Melbourne. The operation involved a role-play in which a hostage being held in a room by foreign intelligence agents would be rescued by ASIS. Unfortunately, ASIS informed neither the police nor hotel staff beforehand. Not only were the premises damaged when officers used a sledgehammer to break down a door, but the masked rescuers threatened hotel staff with the weapons they carried.

The only aspect of the ASIS operation that revealed a modicum of either common sense or judgement was that the trainees were not presented with live ammunition, although traumatised hotel staff were not to know that when automatic pistols and submachine guns were pointed at them. The busy royal commissioner, about to report on Combe and Ivanov, now had another incident to investigate. •

This is an edited extract from Frank Bongiorno’s The Eighties: The Decade that Transformed Australia, published by Black Inc.