When a party nominates a barrier-breaker for president of the United States, we instantly wonder: are the American people ready? Barack Obama’s victory proved Americans were prepared for a Black president. Hillary Clinton’s defeat suggested they weren’t ready for a female president, though the argument can be made that other factors were at play.

Now that Democrats have nominated a woman of colour, the question looms large and can’t be definitively answered until the votes are counted.

Still, early polling is promising for vice-president Kamala Harris. As I noted in the Washington Monthly earlier this week, if November results matched August’s two-way trial heat polling, Harris would narrowly win the national popular vote by about one or two points. She would win Arizona, Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin by equal or slightly higher margins — enough for an electoral college majority. (Soon after, a series of swing state polls from The Cook Political Report with Amy Walter found a one-point edge for Harris in North Carolina.)

The polls have spiked despite sexist and racist attacks from Donald Trump and other Republicans. The vice-president has been demeaned as a “DEI hire.” Some, calling attention to her mid-1990s relationship with former San Francisco mayor Willie Brown, have suggested California’s former attorney-general and US senator slept her way to the top. Trump routinely diminishes her intelligence, calling her “low IQ,” “dumb,” “barely competent” and “not smart enough.” He claims, “She can’t do an interview.”

These attacks have yet to work. But why? Is it because men have matured and aren’t falling for it? Or is it because women are repulsed and flocking to Harris?

Early data is conflicting. But before we look at recent polls, we should understand the history of the gender gap in presidential elections.

Looking at exit poll data from 1972 to 2008 and post-election data analysis using voter files by the political data firm Catalist for the last three presidential elections, we can see the gender gap emerged in 1980.

For the 1972 and 1976 elections, the margin between the Democratic and Republican candidates is about the same among women and men. In 1980, the difference mushroomed to seventeen points. In nearly every presidential election since, except for 1992, the gap has been in double digits.

Since 1992, women have consistently favoured the Democratic candidate. Since 1996, except for 2004, the Democrat has won the female vote by a double-digit margin, typically between eleven and thirteen points.

The Republican edge with men has been less consistent than the Democratic edge with women. Bill Clinton won with men in 1992 and lost them by a point in 1996. Similarly, Barack Obama won them by a point in 2008 and lost them by four in 2012. Al Gore, John Kerry, and Hillary Clinton each lost men by eleven points. Joe Biden kept the male deficit down to six points.

You will not be surprised to learn that two of the three widest gender gaps involve elections with Donald Trump — twenty-four points in 2016 and nineteen points in 2020. (The 2000 election between Gore and George W. Bush featured a twenty-two-point gender gap.)

Because the 2016 exit poll showed Trump winning white women by nine points, Hillary Clinton’s defeat is sometimes attributed to an abandonment by those women. (Catalist pegged the 2016 white women margin at eight points.) But that conclusion was drawn without historical context. White women have firmly sided with the Republican nominee since 2004 (not counting George W. Bush’s one-point edge in 2000).

Compared to 2012, in fact, Hillary Clinton narrowed the white women gap by five points in the exit poll data and by one point in Catalist data. And one group of white women did rally around Hillary Clinton — college graduates. According to Catalist, Obama tied Mitt Romney with college-educated white women while Clinton won them by nine. Unfortunately for her, she also shed support from non-college white women, losing them by eighteen points, four points more than the prior election.

In 2020, Biden’s white women gap was held down to a manageable five points, boosted by a huge sixteen-point win among the college-educated. Compared to Hillary Clinton, his margin was a point worse among non-college women.

Women didn’t abandon Hillary Clinton. Men did. Obama in 2012 won 47 per cent of the male vote, and Biden 46 per cent. In between, Clinton took just 41 per cent, losing men to Trump by eleven points. Non-college men drove the decline. Obama and Clinton each won 41 per cent of male college grads but Obama won 36 per cent of working-class males and Clinton only 28 per cent.

No Democratic presidential candidate had done so poorly with men since Michael Dukakis in 1988. (Bill Clinton also won 41 per cent of the male vote in 1992, but in what was effectively a three-candidate contest that was a plurality.)

Is Kamala Harris’s support among women and men closer to that of Joe Biden or Hillary Clinton? Different polls are telling us different stories.

Harris leads by one point in the most recent CBS News/YouGov poll, for example, and in NPR/PBS News/Marist by three. In both, she pulls 45 per cent of the male vote while hitting the mid-50s among women. That’s roughly similar to Biden in 2020.

(Marist is a rare poll that offers subsample data for white college-educated women, with whom Harris obliterates Trump by thirty-two points. But we should treat subsample data with extreme caution since it comes with high margins of error.)

Polls by Civiqs and SurveyUSA, however, show Harris running up the score with women to offset a weak performance among men. Civiqs has Harris up by four, fueled by 58 per cent support among women and just 39 per cent among men. SurveyUSA’s gender gap is a bit less extreme, with Harris winning 56 per cent of women and 40 per cent of men en route to an overall three-point lead. In these polls, Harris’s support from men is less than what Hillary Clinton received. (Polling levels typically lag final results, however, since undecideds either decide or stay home, and many flirting with third parties eventually vote for a major party candidate.)

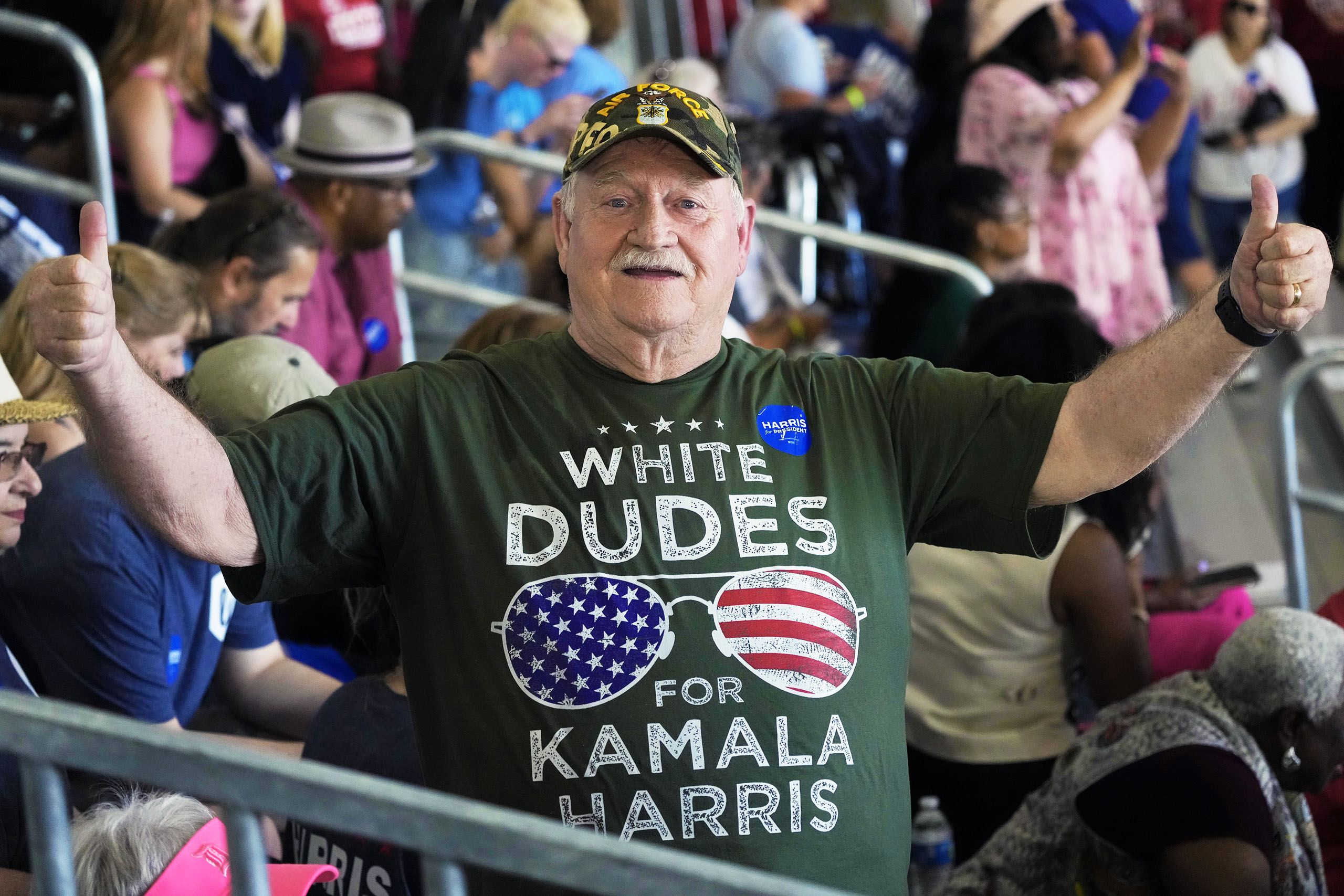

We don’t have a clear enough picture from initial poll data to be able to say confidently that Harris’s confident, energetic, and — to quote her wingman Minnesota Governor Tim Walz — “joyful” campaign style is inoculating her from Trump’s boorish misogyny, but it’s a plausible conclusion. With assistance from his running mate J.D. “Childless Cat Ladies” Vance, Trump may be driving more women than usual into the Harris camp. Or men are not as attracted to rank sexism as they were. Or both.

The converse may also be true. Maybe, as in 2016, today’s polling is illusory. Maybe Trump’s divisive rhetoric needs more time to do its dark work.

But Kamala Harris is not Hillary Clinton, who brought to the 2016 campaign three decades of political scars inflicted by sexist attacks and who suffered considerable damage to her reputation — quantifiable by the steep decline in her favourable ratings — throughout a contentious primary campaign. Harris began her hundred-day sprint to the White House backed by a unified and euphoric Democratic base, propelling a sharp rise in her favourable ratings. The nomination came to Harris without her having to display the ambition that so many voters seemed to find distasteful in Clinton, even though the former secretary of state was simply aspiring to what so many male politicians have.

Barack Obama didn’t end racism in America. But in his historic 2008 campaign he provided a road map for overcoming it in the presidential arena, with unifying rhetoric that showed how common struggles transcended race. Maybe, just maybe, Harris has figured out how to overcome misogyny. •