So, we are to have another Accord? No, more like a festival of bad history, if some members of the commentariat have anything to do with it.

At the National Press Club yesterday Scott Morrison announced not only that he would be abandoning his anti-union “ensuring integrity” bill but also that his government would be bringing together unions and businesses to sort out changes to a broken industrial relations system. “It is a system that has, to date, retreated to tribalism, conflict and ideological posturing,” declared one of the country’s chief tribalists, conflict merchants and ideological posturers.

This is no Accord-style proposal, and there is enough half-cooked history out there already without adding more to the pot. The Prices and Incomes Accord was not a meeting between government, business and unions; it was an agreement and partnership between the Labor Party, then still in opposition, and the Australian Council of Trade Unions. It did not include business. It was not based on the idea of a government sitting down with one interest among many and having a pleasant chat about industrial relations law. It assumed that unions — or at least their leading officials — would be brought into the policymaking processes of government. And to some extent, over the years ahead, that is what happened.

The Accord was a trade-off in which unions agreed to wage restraint in return for the legislative benefits sometimes called a “social wage.” One aim was to contain inflation, which the Labor Party and the ACTU could agree was a problem for both workers and the national economy. Another — especially on the union side — was to ensure that its members would benefit from Labor in government. Medicare is one of the Accord’s progeny. Compulsory superannuation would become another.

Nor was the Accord an effort to reform the industrial relations system. On the contrary, it depended on the existence of strong unions, a centralised system of wage determination and an empowered Arbitration Commission — the combination that had underpinned Australia’s industrial relations system since the early years of the century. Once that system was gradually wound down from the late 1980s and replaced by enterprise bargaining, the Accord became increasingly unimportant, even as it moved through to an eventual Mark VII (or Mark VIII, if you count the one never implemented because Labor lost the 1996 election).

It is also fundamentally mistaken to imagine that having an Accord is somehow at the other end of the spectrum from doing what Scott Morrison and the Coalition have spent a great deal of energy and effort trying to do: coerce the unions. The Accord — if I may borrow an evocative phrase used by the late Peter Coleman in quite another context — was a combination of the “open smile” and the “broken bottle.”

It was all smiles if unions behaved themselves. But if they didn’t — if they were like one of the ancestors of the CFMMEU, the Builders Labourers Federation — they could expect to feel the full force of the government’s iron fist. The BLF was deregistered when it refused to play ball — by federal and state Labor governments. The Federation of Air Pilots was treated with no greater tenderness when it demanded wage increases of almost 30 per cent.

Far from representing some personality change, Scott Morrison’s plans for sweetness and light between government, unions and business look more like cover for his necessary decision to abandon a bill that was going nowhere and had become an embarrassment in a political and economic environment transformed by a pandemic. The iron fist won’t be far away: Morrison will not play to Sally McManus in the way Robert Menzies did to her distant predecessor Albert Monk, or Malcolm Fraser did to Bob Hawke, because he doesn’t have to. Monk and Hawke led an ACTU that represented half (or more) of the workforce, in an industrial relations system that did organised labour plenty of favours. McManus, while widely respected, leads a union movement that enjoys none of these advantages.

The Accord had its critics at the time. Even during the 1983 election campaign, a young shadow treasurer, Paul Keating, in one of the more embarrassing of the campaign’s gaffes, admitted that he did not know whether it would work. It was not a good look for a party that was using the Accord to show that it could rebuild a failed economy in partnership with the unions. For the right, the Accord gave unions too much influence over a government led by a former ACTU president. For critics on the left, all the sacrifices seemed to be on the union side. The benefits to workers seemed meagre, especially once the government became increasingly preoccupied with cutting expenditure during the economic crises of the mid 1980s — which Keating warned might otherwise turn Australia into a banana republic.

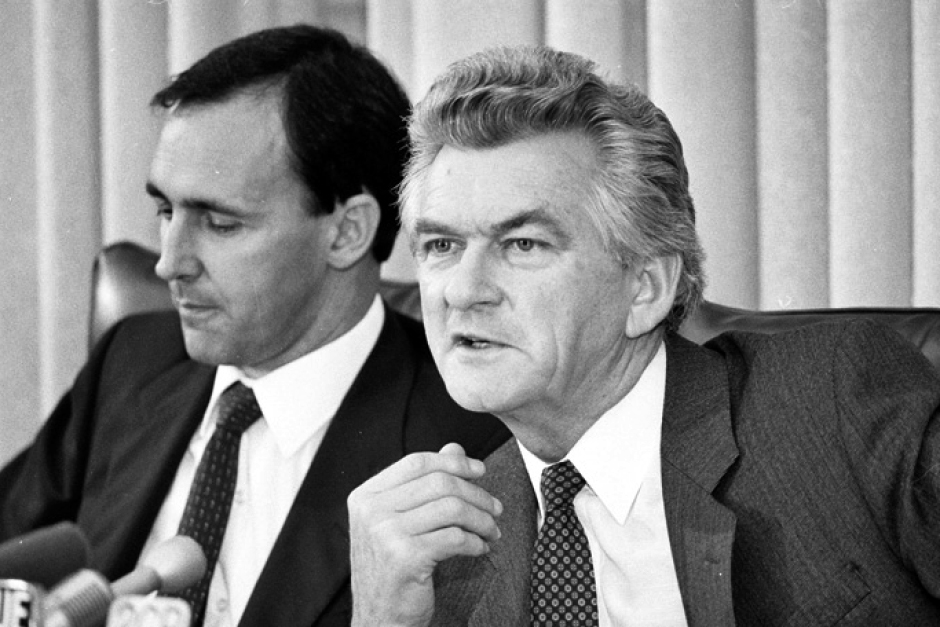

Observers frequently confuse the Accord with the National Economic Summit of April 1983. Held in the House of Representatives chamber of the old Parliament House, the summit was a rather dramatic statement by a new government about its own priorities. It included business as well as unions, state governments and even the odd representative of the community sector. The whole affair was treated as a great triumph for Hawke — he had supposedly signed up both the unions and business to his economic agenda — but it was in many ways an enlarged and polite version of the blokey world of horsetrading and deal-making in which Hawke had flourished in the 1960s and 1970s. Most of the major interests that we would now regard as needing to be represented on such an occasion — First Nations people, women, the unemployed, people with a disability — were absent. It was of its times, a meeting of men in suits.

Those times have changed, but Hawke continues to mesmerise the political class, even on the right, his governing style seemingly the gold standard ever after. He remains the prophet of “consensus” as surely as Menzies is the prophet of “the forgotten people” and John Howard of “the battlers.” “Bringing Australia Together” — a 1983 Labor campaign slogan — is now treated as the only viable alternative to the aggressive and snarling partisanship that seems to have been the default position of Australian politics for a generation. But democracy is about contention as well as consensus.

The Accord envisaged a cooperative but empowered union movement, one that still represented about half the workforce. Its critics on the left today, including political economist Elizabeth Humphrys in an important recent study, argue that it left in its wake a neoliberal economic order and a union movement so bereft of rank-and-file power that it could no longer offer any serious challenge to government or bosses. The kind of sweetheart dealing between unions and employers — often at the expense of members — uncovered by the trade union royal commission was one fruit of its creeping frailty. Another has been the flat wages, wage theft and deteriorating employment conditions — especially for casual workers — that have dogged the economy for years.

If it is far from clear what the unions have to offer Morrison, it’s hardly more so what he can offer the unions. He has placed on the table issues such as “award simplification” (whatever that means); “enterprise agreement making” based on the need to “get back to the basics” (of course we do); casuals and fixed-term employees (about which he offers no views); “compliance and enforcement” (followed by a reference to unions and employers doing “the right thing”); and “greenfields agreements for new enterprises” (at this point, union official breaks out in a cold sweat). There’s not much for unions to get their teeth into here, but plenty that ought to worry them in the hands of a government that has been relentlessly anti-union since the moment it took office.

Is he going to provide unions with greater opportunities to organise than current labour laws allow them? That would go down like a lead balloon among the Coalition’s “base,” business donors and barrackers in the right-wing media. Is he prepared to do anything to encourage union membership, given that he’s recently discovered how terribly helpful unions can be? (After all, unions do have to be paid for, and those who pay their union dues are often underwriting the wages and conditions of the many more who don’t.) What support is he prepared to offer coal workers certain to be restructured out of their jobs in the years ahead? Or are we just going to get continuing reruns of the false hope that workers and communities will have a bright future if only Labor and the Greens can be kept at bay? As ever with this marketing man as prime minister, all that is solid quickly seems to melt into air.

Whatever the outcome of this initiative, let’s not pretend that we are seeing the return of the Prices and Incomes Accord. It had its faults, but it was at least based on the idea of workers getting something in return for stagnant wages. By way of contrast, Morrison offers… what? It’s hard not to see this as an example of the kind of frontrunning and kite-flying Morrison was prone to as treasurer, at least according to Malcolm Turnbull’s recent memoir. •