Exile: The Lives and Hopes of Werner Pelz

By Roger Averill | Transit Lounge | $32.95

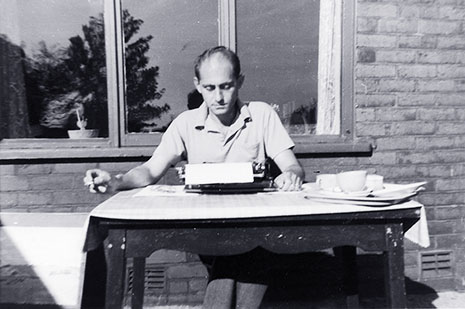

BORN into a German-Jewish family in 1921, Werner Pelz grew up in Berlin as the Nazis were taking hold of Germany. On 1 August 1939, a month before the outbreak of war, his parents sent him to safety in England. There, he was interned as an enemy alien and deported to Australia on the infamous HMT Dunera. He spent the next two years in an Australian camp and then, when many internees were released in July 1942, decided to return to England; he was twenty-one years old.

Pelz spent the next thirty years in a state of spiritual upheaval. He settled down in England, studied theology and became an Anglican priest. “I suddenly came in touch with the Bible,” he later explained. “I came to like it enormously and it meant very much to me and then, through a rather traumatic experience, when the news of the concentration camps came through and I knew that my parents had been among those who were in them, probably from a kind of panic, I fled into some kind of belief which had all the answers.”

Pelz proved to be a turbulent priest. He rejected the institutional trappings of the church and discouraged parishioners from attending church only out of a sense of obedience or obligation. He was secretly pleased when the size of his congregation shrank. With his wife, Lotte, likewise a refugee from Nazism, he published works critical of the religious establishment, including the provocatively titled God Is No More. The couple were prominent anti-nuclear and peace activists.

Pelz broke with the church in the early 1960s. He turned to sociology and completed a PhD, eventually returning to Australia to take up a position at the young La Trobe University in 1973. The next thirty-three years were his most settled period. His anti-institutional ideas had found favour in the ferment of the 1960s, and the anti-authoritarian atmosphere at La Trobe suited him down to the ground. He loved teaching and inspired affection among his students. He brought the German custom of the Doktorvater – the close mentoring relationship between supervisor and student – to his supervision of PhD students. In one of his most optimistic letters he wrote with enthusiasm about the beginning of another university year, though the tone was undercut by the sense of insecurity that never quite left him: “So I find myself once again in an almost ideal situation, to be able to teach what I love teaching – and, as always, I feel a little frightened as to why I have deserved this and how long it will last.”

Roger Averill was one of the students inspired by Pelz. In Exile he recounts Pelz’s life and reflects on how it influenced his own, interspersing episodes from his teacher’s past with his own diary extracts as he visited Pelz during his final illness. After Pelz’s death in May 2006 Averill sorted out Pelz’s papers and decided to write his biography.

It turned out to be a confronting experience. Averill was forced to delve into the private world of Pelz’s troubled first marriage and Pelz’s feelings of guilt about his son’s unhappy childhood and adolescence, which he failed to recognise and deal with at the time. “How, then, could I not be disillusioned by learning the details of how he hurt and disappointed others?” Averill writes. “Aren’t biographies (honest ones, at least) always journeys from enchantment to disenchantment, an alchemy in reverse, the gold of an admired figure reduced by fire to its basest metal?”

The strength of Averill’s approach lies in the intimate insights he gives us into the lives of Pelz and those close to him. In addition to his conversations with Pelz, Averill interviewed Pelz’s friends, his son and his sister, and draws on unpublished manuscripts and correspondence. This approach is especially fruitful in portraying the latter part of Pelz’s life. Here, Averill is able to show how Pelz’s teaching continued to be influential even after his retirement, when he lectured at the University of the Third Age and established reading and writing groups in Healesville on Melbourne’s northeast fringe. The elderly Pelz achieved reconciliation with his son, Peter, to whom the book is dedicated, and experienced strong attractions to two women who reawakened his passion after the death of his second wife.

But the very intimacy of Averill’s approach robs his account of a broader context, and it can be difficult to see the wood for the trees. Averill shares Pelz’s scepticism about categorisation and abstraction and this militates against a clear portrait of his intellectual contribution. The clearest statement we get concerns Pelz’s openness to uncertainty. “As a priest Werner encouraged his parishioners to abandon religiosity, now as a sociologist he was encouraging his students to abandon social science. Both were calls for a creative acknowledgement of uncertainty. For uncertainty is, he believed, fundamental to our existential and social realties – indeed to our humanity.”

It is possible for a biographer to be too close to his or her subject. Averill is aware of this problem and he inserts himself as a character in the book to make his involvement clear. But this only emphasises his inability to withdraw and allow the broader setting to emerge. Placing Pelz’s biography within Australian immigration history, for example, could have provided an illuminating context. Ultimately, Pelz made a home in the land to which he was first exiled on the Dunera. The unobtrusive but important contribution he made to local cultural life in outer Melbourne resonates with the contributions that German-Jewish refugees made in diverse ways to Australian cultural life after the second world war – contributions that have transformed Australian life.

Averill gives us a highly personal account of Pelz’s life but this life was also part of the wider story of exile and later migration to Australia. More explicit treatment of this wider story would have made this biography even more interesting. •