Donald Trump’s attempt to use emergency powers to fund a massive wall along the US–Mexico border has been widely ridiculed, and for good reason. His characteristically breathless claims that the United States “cannot be safe” without “The Steel Barrier” to stop “Criminals, Gangs, Human Traffickers, Drugs & so much other big trouble” don’t bear much scrutiny.

Official statistics show that unlawful movement across the southern US border is at a twenty-year low, and that most undocumented migrants don’t sneak in overland but arrive through normal channels and then overstay their visas. Experts point out that illicit drugs, too, are generally smuggled through official points of entry (or perhaps tunnels) rather than across the unfenced frontier. Investing US$20 billion or more in extra walls won’t solve the problem Trump claims he is trying to fix.

But it’s far too easy for us to smugly criticise Trump’s plan. Australia already has its own equivalent of his pointless wall — the continued offshore processing regime in Manus and Nauru. What is worse, it is a folly that enjoys bipartisan support and also costs an enormous amount. Federal budget papers show that offshore processing cost $1 billion or more in every year from 2013–14 to 2017–18.

Defenders of the policy claim that this extravagant use of public money has achieved the twin policy goals of maintaining the integrity of Australia’s borders and saving lives at sea. John Menadue, a former secretary of the prime minister’s department, dismisses such arguments as propaganda. Even if the position is argued sincerely, it is hard to sustain, since offshore processing has been far from crucial in preventing asylum seekers from reaching Australian territory by sea.

As another former senior public servant, Paddy Gourley, wrote recently in Inside Story, boat numbers had already slowed after the Rudd government accelerated the assessment of Sri Lankan asylum seekers and quickly returned those who weren’t found to be refugees. Tighter visa controls in neighbouring countries, no doubt encouraged by Australian diplomacy and technical assistance, also reduced the numbers boarding boats to Australia.

But the most powerful measure was the interception and turnback of boats by the navy and the Australian Border Force. This was true in the Howard era, and it has been just as true under the prime ministerships of Abbott, Turnbull and Morrison. According to the Parliamentary Library, since late 2013 at least 810 people on board thirty-three boats have been turned, taken or assisted back to their point of origin. No vessels have managed to reach Australian territory via established smuggling routes from Indonesia or Sri Lanka in that time. The only boat to get here — a fishing trawler carrying seventeen people from Vietnam in August 2018 — came a different way and landed in far north Queensland.

It is disingenuous to assert, as Scott Morrison has, that resettling refugees from Manus and Nauru in New Zealand amounts to “putting a bit of Kiwi sugar on the table for people smugglers.” Even less persuasive is Peter Dutton’s claim that the medivac bill to allow sick refugees to be treated in Australia would be read as a “green light” to the maritime smuggling trade. If anything was going to help smugglers market their services, it would have been the prospect of eventually reaching the United States via Nauru or Manus; yet the boats didn’t return when Malcolm Turnbull struck a resettlement deal with Barack Obama in 2016. Nor did they return between 2002 and 2006, when the Howard government quietly resettled a significant number of people from Manus and Nauru in Australia.

The only conceivably plausible counterargument — put to me privately by senior officials involved in Operation Sovereign Borders — is that the smugglers could overwhelm Australia’s border defences by launching a coordinated action, sending so many vessels simultaneously that it would be impossible for the navy to intercept them all. According to this argument, continued offshore detention remains a necessary deterrence. But this outlandish scenario would require an unlikely degree of coordination between rival smuggling outfits willing to take a massive financial gamble.

To understand why, it is important to remember that passengers generally don’t pay the smuggler in full for the passage to Australia; instead, they deposit funds with a trusted third party. Researcher Khalid Koser has followed the money trail of the smuggling networks and found that the cost of passage is usually paid to a hawala, or money changer, and held in trust. “The money is only released by that third party to the smuggler once the migrant has arrived safely in his or her destination,” he says. Koser calls this a money-back guarantee on smuggling: “If you don’t make it to your destination safely, I as a smuggler get nothing at all — nothing.”

Research cited in a parliamentary library report also found that smugglers used payment systems “designed to minimise the risk to clients,” including “using intermediaries who passed on parts of the fee only as stages of the journey are completed [and] offered guaranteed services, whereby further smuggling attempts are free of charge if the first is unsuccessful.” It would be a reckless business operator who chanced their arm at beating Australia’s naval defences under these operating conditions.

That’s not to say that Australia’s turnback policy is impregnable. It remains dependent on maintaining good diplomatic relations with neighbouring countries, for example. If relations with Indonesia were to falter, as they have in the past over East Timor — and might in future if, say, Australia pursues a decidedly pro-Israel foreign policy — then sections of that country’s security forces may see assisting smugglers (or engaging in smuggling themselves) as a way to hit back at Australia. If political oppression or ethnic violence were to generate a significant outflow of refugees from Indonesia itself — a remote but not unthinkable scenario given the nation’s history — then Australia’s turnback policy would immediately become unsustainable.

Boats could also start arriving from other countries. Malaysia hosts an estimated 40,000 Rohingya displaced from Myanmar, for example, and it’s conceivable that some of them might try to make their way to Australia by sea. In such an eventuality, the Malaysian government is unlikely to accept turnbacks, and Australia would surely not send the stateless Rohingya back to Myanmar like it has sent “failed” asylum seekers back to Sri Lanka.

The security-minded might see such possibilities as a reason to maintain an offshore processing capacity, but they certainly don’t justify the continued refusal to resettle the people left on Manus and Nauru. Boat turnbacks make this both unnecessary and cruel. As Robert Manne wrote recently in the Saturday Paper, leaving the remaining 1000 or so adults on Manus and Nauru is much worse than a breach of the ethical position that human beings must never be used as a means to an end: “The lives of the 1000 are being destroyed not as a means to an end but for no reason.” As a philosopher friend put it to me, the means has now become the end; we maintain offshore processing in order to maintain offshore processing. It achieves no practical purpose, only the symbolic job of signalling to the Australian electorate that both major parties are “tough on borders.”

To draw on the thinking of early twentieth-century German jurist Carl Schmitt via the contemporary philosopher Giorgio Agamben, what began as an emergency measure — a circuit-breaker to stop a surge in boat arrivals — has become standard operating procedure. Introduced in response to extraordinary circumstances, this “state of exception” has been rendered routine, reinforcing and exaggerating the security mindset that accompanied its inception. Once certain thresholds of policy and action were crossed, they became unexceptional, and the administration of Australia’s immigration program and border controls has changed across the board as a result.

It is this “state of exception” that enables normal government procedures to be set aside so that $423 million worth of contracts can be granted to a company with little track record in providing the relevant services — a company run by directors of questionable character and registered to a beach shack on Kangaroo Island. Official efforts to explain the Paladin affair since it was exposed by the Australian Financial Review have been far from convincing. The case is reminiscent of the cold war–era defence procurement scandals in the United States, another normalised “state of exception,” when the Pentagon discovered that it had been shelling out for “$7600 coffee pots and $400 hammers.” The Paladin affair is not a failure of procedure; it is an example of the kind of procedures that become normal under a “state of exception.”

This is not the first time procurement for offshore processing has been scrutinised and found wanting. In 2016 and 2017, the Australian National Audit Office published two reports criticising the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (as it was then) for its handling of contracts worth $3.386 billion for garrison support and welfare services on Nauru and Manus. Garrison support includes security, cleaning and catering services; welfare services include healthcare, recreation and education. The businesses involved were not pop-up companies like Paladin but established corporations including Broadspectrum (formerly Transfield Services), KPMG, Serco, G4S and, from the non-government sector, Save the Children and the Salvation Army.

The first audit report, which dealt with procurement, identified “serious and persistent deficiencies.” The audit concluded that the department “significantly increased the price of the services without government authority to do so,” not least by cancelling a planned tender and extending an existing contract with Transfield instead. The second report, on contract management, found that the department had “fallen well short” of effective practice. The audit could find “no documentation of the means by which the contract objectives would be achieved” and judged that contract variations totalling over $1 billion had been made without “a documented assessment of value for money.”

In a statement in response to the first audit, the department justified its record “in the context of the unique operational environment the department faced at the time”:

The department met the requirement of the government of the day in an environment that was high-tempo and complicated by logistics and procurement activities in foreign countries. Delegates were required to make decisions on complex matters within very short timeframes. It remains the department’s position that decisions taken in this period were reasonable under the circumstances. The environment remains extremely complex.

Having invoked a “state of exception,” the department then normalises it, by arguing that the average annual cost of operations had been “relatively stable,” ranging from $427,000 per person in 2012–13 to $464,000 per person in 2015–16. The fact that the government was shelling out well in excess of $1000 per person per day on offshore processing was less an exceptional circumstance than a mark of competent administration.

Since the Paladin affair broke, more stories of dubious contracts and poor management have emerged. The Guardian reported that the Australian government paid Pacific International Hospital $21.5 million over ten months to provide healthcare on Manus Island “without finalising a proper contract.” The Australian reported that PNG-based NKW Holdings Ltd received an $82 million contract to provide catering and site-management services on Manus without a competitive tender. The contract ended up costing “$1390 per resident per day,” said the paper, far more than rival companies charge for similar services on mine sites. Both firms had links to influential political figures in Papua New Guinea.

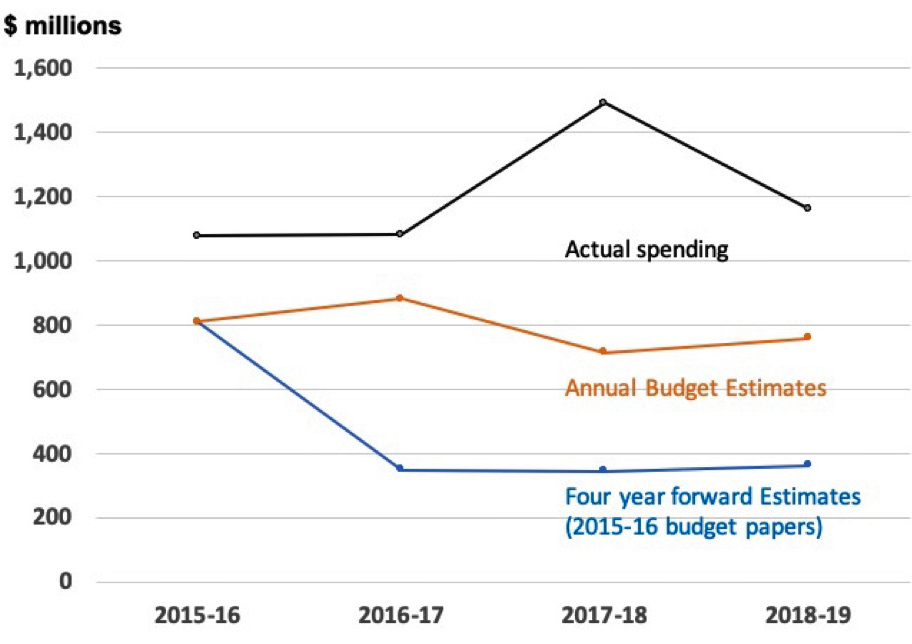

This helps explain why spending by the home affairs department on “illegal maritime arrival offshore management” last financial year was close to $1.5 billion, more than double the budgeted $714 million. Spending this financial year is anticipated to top $1.16 billion, again massively higher than the budgeted $760 million. This pattern of blowouts is well established.

Offshore detention spending blowouts 2015–16 to 2018–19

Home affairs portfolio budget statements only include the day-to-day expense of running the offshore program. Although the costs of setting up offshore facilities aren’t transparently reported, we know from answers in Senate estimates hearings that capital expenditure totalled $816 million in the first three years of the policy. As UNICEF and Save the Children point out, the true costs of offshore processing are higher still, given the money Australia spends “to maintain, interrogate and defend the current approach,” including responding to legal challenges and inquiries by parliamentary committees and regulatory bodies. Resources have also been expended on extensive but largely failed diplomatic efforts to negotiate third-country resettlement deals.

Sticking to the numbers we can confirm, the cumulative cost of offshore detention in the six years since it was reintroduced by the Gillard government is at least $7.6 billion, as the chart below shows. It might be less than the US$20 billion Trump wants to waste on a border wall, but it is far more as a proportion of government revenue and national income. As Daniel Webb from the Human Rights Law Centre points out, Australia’s annual spend on offshore detention is “more than five times the UN refugee agency’s entire budget for all of Southeast Asia.”

What is at issue here is not just the neglect of due process, nor the waste of money that could have been spent more usefully, nor even the terrible human cost of lives damaged and destroyed, though we should never lose sight of that. This behaviour has wider implications and opportunity costs as well. By transforming immigration into a security issue, the government has generated avoidable problems and dropped the ball on other complex policy issues.

In separate articles, former senior immigration officials Abul Rizvi and Peter Hughes have recently slammed the government’s broader immigration record. Hughes says the Abbott, Turnbull and Morrison governments have “delivered an immigration shambles — a policy vacuum, a degraded administration and huge processing backlogs.” Rizvi says the “visa system, and by implication our borders, have never been so out of control.”

The evidence to support these assertions can be found in home affairs data. For example, between December 2013 and December 2018 the number of people in Australia on bridging visas more than doubled, from 93,000 to 189,000. Generally, people on bridging visas are waiting for the department to process their application for a substantive visa, or else have sought review of a decision and are waiting for the Administrative Appeals Tribunal or the minister to make a determination. The caseload of matters on hand in the AAT’s Migration and Refugee Division blew out from fewer than 17,000 on 30 June 2016 to more than 44,000 on 30 June 2018.

Meanwhile, the attorney-general stands accused of stacking the AAT with “scores of former conservative politicians, failed candidates, former staffers, party members, donors and other mates.” The AAT is receiving (and rejecting) growing numbers of appeals by asylum seekers from China and Malaysia. Given that nationals from these two countries are unlikely to be recognised as refugees, this suggests deliberate and possibly systematic abuse of the system, with people flying into Australia on visitor visas (or being brought in by labour contractors) and then lodging applications for protection as refugees. Since a claim takes years to wend its way through clogged bureaucratic and legal systems, the applicant can be confident of securing the right to live and work in Australia for quite some time, though probably in exploitative conditions for well below award wages. As Rizvi argues, immigration backlogs and processing delays are “a honeypot for the spivs; the carpetbaggers; the people smugglers.”

At a time when conflict, oppressive regimes, resource constraints and climate change are displacing ever-growing numbers of people around the world, Australia has spurned international efforts to manage migration more collaboratively through the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration — despite the fact that Australian diplomats worked assiduously on its development with other participants in the Bali Process, which Australia co-chairs with Indonesia.

Returning asylum seekers to Indonesia and Sri Lanka may prevent boats arriving on Australia’s shores, at least for now, but it does nothing to address the bigger issue of forced migration. It is easy to be cynical about efforts to build a coherent humanitarian regional response to human displacement, and negotiations of this kind are by their nature tediously slow. Yet the significant, incremental advances made by the Centre for Policy Development’s Asia Dialogue on Forced Migration show not only that progress is possible but also that high-level support exists in neighbouring countries for a truly cooperative regional framework to manage displacement and counter human trafficking and smuggling in a humane and dignified way. It is impossible to know what progress we might see if Australia devoted more than $1 billion a year to developing such an approach with neighbouring countries, instead of spending it on warehousing vulnerable people in the Pacific.

Perhaps worst of all, the securitisation of immigration policy has severely damaged the vision of Australia as a diverse and inclusive nation in which migrants quickly become citizens with the same rights and responsibilities as the established population. This is not just the result of race-baiting comments by senior politicians about “African gangs,” or the pandering to claims that migrants are to blame for rising house prices, stagnant wages and urban congestion, or the repeated use of statistics that exaggerate the impact of migrants on population growth in Sydney and Melbourne, or even recent assertions that bringing a few hundred sick refugees here for treatment will force Australian citizens off hospital waiting lists or out of public housing. It is also the result of the push to make the pathways to permanent residency and citizenship harder and longer, through poor policies, misguided legislation, basic maladministration and neglect.

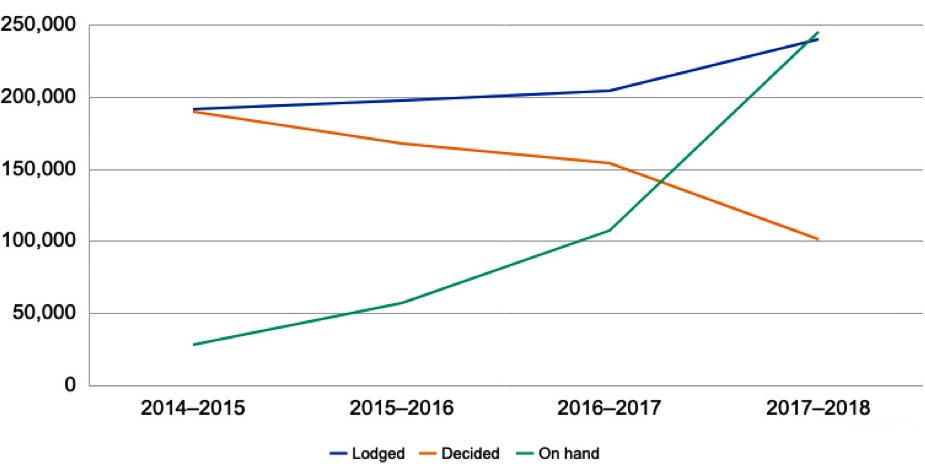

Alongside the backlogs in visa processing is a backlog in approving applications for citizenship. According to another Audit Office report, citizenship applications on hand blew out from around 23,000 in June 2014 to more than 244,000 in June 2018. The claim that delays are caused by additional security screening is unconvincing, since applicants for citizenship are, by definition, permanent residents who have undergone intense vetting to get a visa. But the normalised “state of exception” justifies and enables such groundless responses.

Citizenship applications lodged, decided and on hand per year

Source: Australian National Audit Office

The effects of the securitisation of immigration have also bled across from home affairs into other portfolios, most notably defence. The Sydney Morning Herald reports that the Australian Defence Force has had to cancel a range of international exercises and patrols because it is “picking up the slack” for the Australian Border Force. Leaked briefing notes reveal that the Border Force is unable to adequately staff and maintain its own fleet of vessels and aircraft.

Whether the Coalition or Labor wins the federal election, the incoming government will need to appoint a highly capable minister to renew immigration policy and rebuild administration. Energy, imagination and resolve will be needed to repair the damage inflicted on the ethos of citizenship-based multiculturalism that underpins an inclusive migrant society, and to grasp the opportunity to work closely with neighbouring countries to craft a coherent response to forced migration. Dealing with legitimate public concerns about the scale and nature of Australia’s temporary and permanent migration intakes while fending off hate speech and xenophobia will call for deft political skills. As both Paddy Gourley and Peter Hughes argue, an incoming minister may also have to unpick the failed experiment of the home affairs portfolio, which will require careful thought and patient negotiation.

Sadly, such a combination of qualities is not easily found in the parliament, and it’s hard to blame senior politicians for preferring a less challenging portfolio. For whoever ends up in the chair, however, the essential first step will be to end Australia’s “state of exception,” dismantle the expensive and punitive border wall represented by offshore processing, and help those remaining on Manus and Nauru to find a safe home and rebuild their lives. •