When I started studying the Dunera internees in 2013, I didn’t expect I’d still be at it eight years later. I worked first with the historians Ken Inglis, Jay Winter and Carol Bunyan, and what a privilege it was. When Ken died in December 2017, Bill Gammage joined our collective, and together we finished the project Ken had begun. The manuscript of the second volume of Dunera Lives went to the publisher just before Christmas 2018, and there I expected my engagement with Dunera to end. But I was wrong, and spectacularly so. Dunera work continues, spurred on by rich and unexpected developments.

Many of the families of the roughly 2050 Dunera men have in their keeping wartime keepsakes passed to them by fathers and grandfathers. Over the past three years many of them have contacted me, wanting to donate their treasures to public institutions so that others may also enjoy them. I help where I can, providing introductions to the museums and libraries I know will care for and celebrate the collections. My spare room has become a halfway house for artefacts on their way from private homes to the public sphere.

Curators may shudder at that thought, but I think it’s wonderful. Each day I have privileged glimpses of rare artefacts — paintings, sketches, letters, perhaps an artist’s beret or a travel trunk — that tell vivid stories of people’s lives, of hope and loss in a world at war. Just last month the son of a “Dunera boy” entrusted to my keeping the scores of letters his mother and father sent each other during the war years. In that treasure trove is a tale of love; but other collections can devastate. I have read letters exchanged by Dunera internees, safe in Australia, with mothers, fathers, sisters and brothers trapped in Nazi Europe.

The most intimate of these collections reveal details about Dunera internees of whom we knew nothing when writing the books. Of the great majority of the “Dunera boys” we know only a little, and sometimes nothing other than the biographical bones — name, age and homeland — offered on wartime forms. Many, and probably most, didn’t speak publicly about their lives, and especially about their wartime lives as unfortunate souls arrested and imprisoned without fair reason. For some, this history evoked pain; others preferred to look ahead, never dwelling in the past. Some didn’t want the Dunera experience to colour how their lives and careers were interpreted.

Paul Mezulianik was one of these silent men, his Dunera history not for sharing. I first heard his name in January 2019 when Æone Shrimpton, his stepdaughter, wrote from England about the possibility of donating his art collection to an Australian home. A little over two years later, an exhibition of his work is showing at Tatura Museum, near Shepparton in northern Victoria. In presenting a selection of those artworks for the first time, the staff at Tatura Museum and I have taken the liberty of delving into his past. We do so to honour an individual and tell something of his unique story. About 2000 Dunera stories still remain to be told.

Paul Mezulianik was born to Rudolf Mezulianik, a sales representative, and his wife Gisela (nee Wien) in Vienna on 12 November 1921. Rudolf, who had been raised as a Catholic, had left the church on 11 July 1917 to marry Gisela, or Gitel, who was Jewish. Until the late 1930s the couple were part of Vienna’s Jewish community. On 21 March 1938, just days after Hitler came to Vienna’s famed Heldenplatz to proclaim Germany’s incorporation of Austria, Rudolf left the community. Gisela followed his lead on 19 June 1939.

Paul, raised in the Jewish faith, was baptised on 28 November 1938, shortly after the anti-Semitic violence of Kristallnacht. He was seventeen. Later he would tell Australian officials that he was Catholic, but he wasn’t. His creed was atheism.

An only child, Paul studied at a primary school in Vienna’s fourth district, then for three years from 1931–32 at the Akademische Gymnasium, a high school of excellent reputation. But his marks were so poor that he couldn’t continue to fourth year. Whether he abandoned his studies or continued them elsewhere isn’t known.

Paul remembered Hitler declaring the Anschluss. In the months that followed, the anti-Semitism inherent in Nazi rule and law began to close in on him and the Mezulianik family. On at least one occasion, when Nazi officials came calling, brave neighbours protected Gisela. As the Nazi threat pressed ever harder, queues at foreign embassies lengthened. Jews and others in desperate need of safe haven applied for refuge in friendly countries, with the United States the most popular of potential destinations.

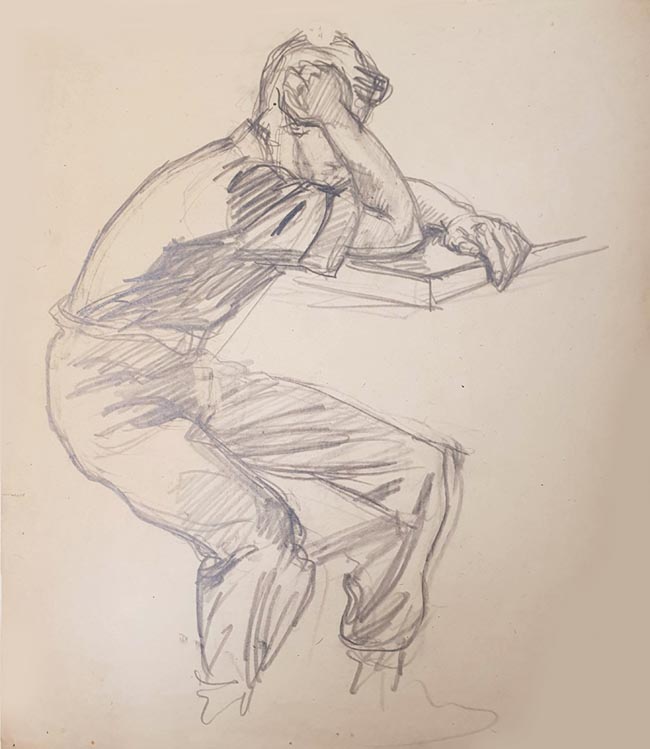

“Certain pieces appear to depict scenes and characters from the years of his internment”: Undated sketch by Paul Mezulianik.

Paul applied for a visa at the American embassy in Vienna in December 1938, but he was denied passage to the United States. It was a common story: the Western liberal democracies were slow — immorally so — to respond to the humanitarian crisis in Europe. The Society of Friends, known as Quakers, eventually arranged his passage to Britain in May 1939, with his residency guaranteed by a British man married to one of Paul’s Austrian friends. While his parents remained in their flat in Vienna — where they would survive the war — he began work on a farm in Yorkshire.

On 16 May of the following year, months into the war, Paul was one of the thousands of Germans and Austrians to be stung by the illiberalism that swept Britain following German military advances. Worried about the possibility of Nazi agents hiding among Germans and Austrians who had sought sanctuary in Britain, Churchill and his government authorised mass arrests. With this one bureaucratic act, thousands of refugees from Nazism were rendered “enemy aliens,” Britain their sanctuary no more.

Churchill’s government wanted enemy aliens as far away as possible from Britain and the war. Paul would tell his family of being deported on the SS Arandora Star, which was sunk by enemy action in July 1940, on its way to Canada, with about 800 lives lost. He remembered being pushed from the foundering vessel into the sea, then dragged from the waters of the Atlantic onto a lifeboat. With more men in the water than space in lifeboats, many of those who survived the sinking soon drowned.

Paul’s account echoes that of another Dunera internee, athletics coach Franz Stampfl. Although no evidence exists to put him aboard the Arandora Star, Stampfl told of surviving its sinking. Paul’s name doesn’t appear on passenger manifests either, or in official documents as a survivor of the sinking, and there is no particular reason why he should have been on the ship. The Arandora Star carried internees about whom the British authorities had political doubts, of which Paul was unlikely to be one. He was probably a category C “enemy alien,” meaning that authorities felt he posed no threat to Britain’s security. Moreover, he arrived in Australia with an intact suitcase and contents, a circumstance extremely rare among Arandora Star survivors. This is not to say that Paul, and Stampfl, weren’t on the Arandora Star, but simply to note that history doesn’t show it.

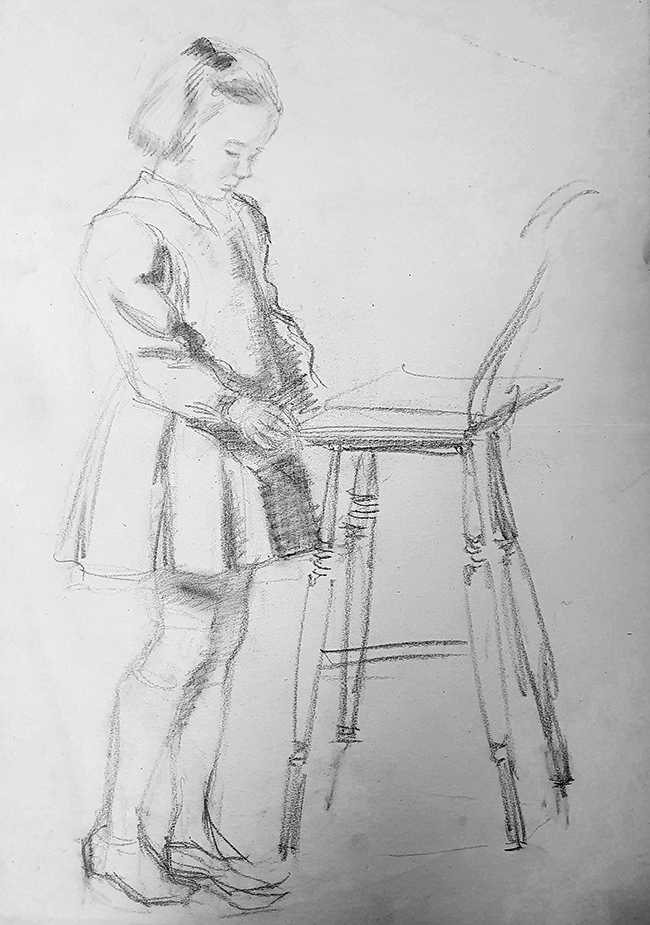

Undated sketch by Paul Mezulianik.

A week after the Arandora Star’s survivors were returned to land, the HMT Dunera departed Liverpool for Australia, carrying more than 2000 of Churchill’s “enemy aliens.” In Dunera terms, Paul was not destined to spend long in Australia. He was held at Hay, in New South Wales, from September 1940 until May 1941, where he lived in Camp 8, Hut 20. One of his hut mates was Heinz Schloesser, whose remarkable life inspired Belinda Castles’s novel Hannah and Emil. Then he was part of the mass movement of Dunera internees to Tatura, in Victoria, where he remained until July of the next year. His return to Britain having been approved, he boarded the TSS Themistocles in Melbourne on 18 July 1942.

Paul’s closest Dunera friend may have been Rudolf Stern, from Cologne, whose birth date, 3 May 1924, made him one of the youngest internees. The two men kept in touch after Paul returned to London. In one letter, Rudi asked Paul to help find him a job in London. Though probably written in Tatura, the letter was sent from the Liverpool transit camp in Sydney, where Dunera men intending to return to Britain were housed while awaiting passage. Rudi died on 29 October 1942 when the MV Abosso, the transport on which he was returning to Britain, was sunk by a German submarine northwest of the Azores. Paul carried the sadness of Rudi’s death for the rest of his life.

Like so many former Dunera internees facing hostility from people who assumed they were German, Paul gave thought to changing his name. His entry in the London Gazette’s list of newly naturalised Britons in January 1950 reads:

Mezulianik, Paul (known as Paul Julian); Austria; Artist; 12, College Road, Isleworth, Middlesex. 22 December, 1949.

Did he want a British name to accompany his British identity? If he did, the thought was fleeting. He appears not to have used the surname Julian, or at least he didn’t formally register the change. His family — he married Patricia, mother to his son Stephen, in 1944, and Esilda, Æone’s mother, in 1963 — knew him only by the name Mezulianik.

After he returned to Britain, Paul took a factory job making aircraft instruments. Once the war was over he turned to film, working initially in animation for Gaumont-British Animation, then for other companies. His animation credits include the 1954 version of George Orwell’s Animal Farm. His work won acclaim, leading eventually to a position as director of the Special Animations Unit for Rank Screen Services. Later he made prize-winning television advertisements for Dorland Advertising, which in time became part of the Saatchi & Saatchi empire.

Success allowed for early retirement, at age sixty, and time to indulge his passions. He gardened, listened to music and played the piano, and travelled widely with Esilda — to Europe, the United States, Africa, and islands of the Indian Ocean. Each year he visited his parents in Vienna, maintaining this annual pilgrimage after Gisela died in 1969 until Rudolf’s death in 1978. Paul died on 21 January 2019, aged ninety-seven.

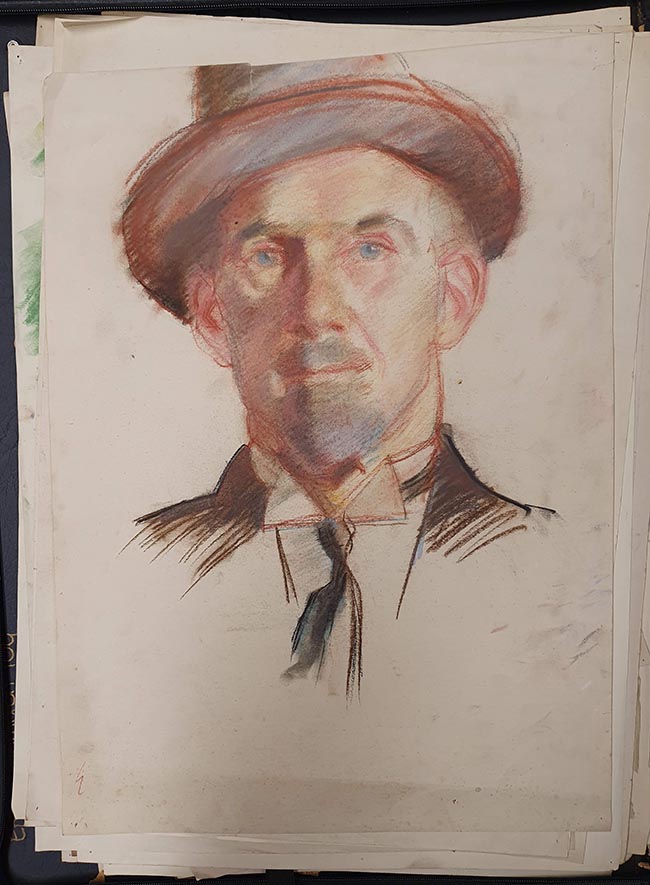

Undated sketch by Paul Mezulianik.

A month before Paul’s death, Æone Shrimpton, his stepdaughter from his second marriage, uncovered a trunk in the attic of the Berkshire house he had shared with Esilda. For decades Paul had hidden his artworks, about 250 in number, from his family. They are almost exclusively figure drawings, studies of human emotions and form, and together they show a fine hand, charting his development as his technique and use of colour became more refined. Certain pieces appear to depict scenes and characters from the years of his internment, and the poor quality of much of the paper suggests that at least part of the collection dates to wartime.

The many nudes prompt the thought that Paul might have joined a life-drawing class, but some of these images, too, may have been sketched during his internment. Artists who could draw the female form found their work highly sought after among the all-male Dunera population, who gave money, cigarettes or other rewards in exchange. The African men and women Paul depicted may have been sketched aboard the TSS Themistocles, which called at Durban and Freetown on his return voyage to Britain in 1942.

By the time of Æone’s discovery, Paul was blind, suffering dementia, and unable to answer questions about the works and his motivations as an artist. He may not have answered them anyway.

Paul was not an easy person, says Æone, with love. Confined to a nursing home late in life, he continued to play piano while complaining bitterly, in Æone’s words, that it wasn’t a grand. He loved gardening and found enjoyment in growing fruit, vegetables, dahlias and zinnias, though that pleasure also showed his pernickety ways: dahlias and zinnias were the only flowers he liked, and the only species he grew. He was given to doubts about his abilities. He was an outstanding pianist, but never considered himself as such. Did he hold similar reservations about his art?

And there was the matter of the war, about which Paul was reluctant to speak. What Æone does know of Paul’s experiences came from her mother, who was also hesitant. In 2014, when Æone asked Esilda in her last days about Paul and the sinking of the Arandora Star, “she became very distressed and it seemed to haunt her.” Æone decided not to tell Paul she had found his art collection.

The Austrian historian Elisabeth Lebensaft was another who learned that Paul preferred to leave the past undisturbed. He resisted her request for information, replying politely but firmly that he remembered almost nothing of the Dunera and his internment. At some point he did tell his friend Fritz Sternhell (1924–2020), of Oxford, something of his experiences: perhaps discussing the past was easier with those who also had lived the Dunera story. Fritz returned to Britain on the same ship as Paul, the TSS Themistocles.

Dunera wasn’t the only source of pain in Paul’s past. In the years after the war, he conducted a long affair with the fiancée and, later, wife of his best friend. This was Esilda, Æone’s mother, whom he later wed. As always, such circumstances had costs. Paul became estranged from Stephen, his only child, who later changed his name, further distancing himself from his father. When Paul died, Æone and her husband Christopher engaged an agency to locate Stephen so he could have the opportunity to come to the funeral. He was found, and attended, but hasn’t been in touch since. The Mezulianik lineage is lost.

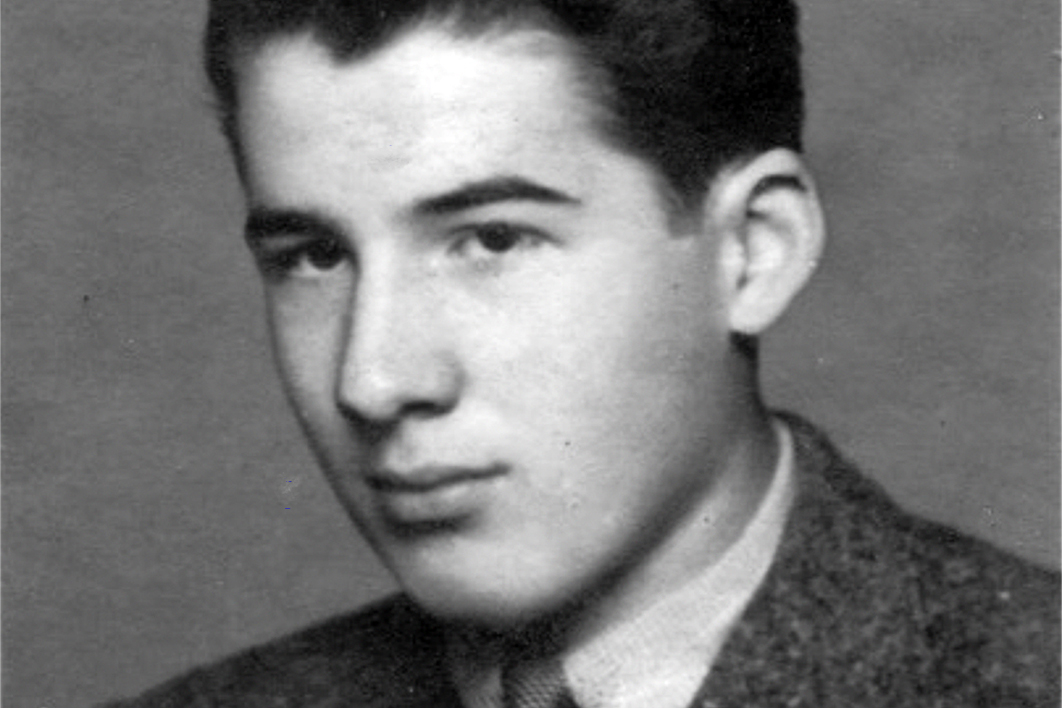

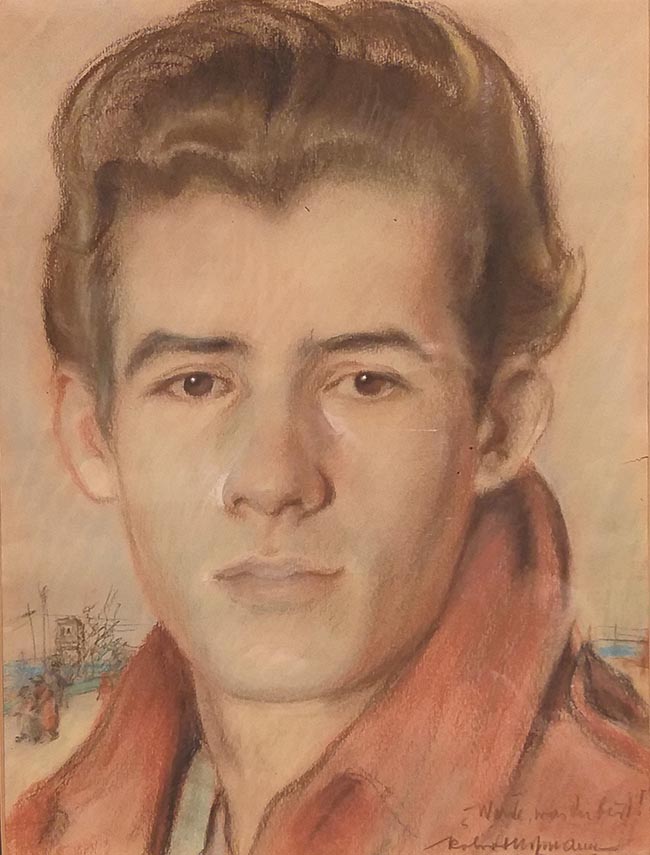

“Werde, was Du bist!” Robert Hofmann’s portrait of Paul Mezulianik, c. 1941–42.

For only one piece in Paul’s collection, and in this exhibition, is the exact provenance known: a portrait of Paul by the acclaimed Austrian artist Robert Hofmann, a fellow Dunera internee. Hofmann, who was fifty-one when he arrived in Australia, was an artist of considerable reputation, winner of the 1922 Prix de Rome and one of Europe’s finest exponents of portraiture. Were the two men friends? Did Hofmann help Paul refine his touch and method?

The portrait, completed at Tatura in 1941 or 1942, shows a strikingly handsome young man, pensive and reticent. Hofmann captured a sense that the subject holds on to something not to be shared. His inscription on the portrait, though hard to decipher, appears to read: “Werde, was Du bist!” (“Become what you are!”) The portrait hung in Paul’s house throughout his postwar life. This artwork was for sharing, his own works were not. He kept his history close. •

Become What You Are: The Art of Dunera Boy Paul Mezulianik is showing at Tatura Museum until July. This article is an expanded and edited version of an essay in the exhibition catalogue. After the exhibition ends, the Mezulianik collection will be donated to the State Library of New South Wales.