Between 1978 and 2012 China achieved the longest period of sustained rapid economic growth in recorded history. Growing at an average annual rate of 10.0 per cent (as measured by real GDP) it went from being the world’s eleventh-biggest economy (in purchasing power parity) or its ninth-biggest (in US dollars at market exchange rates) to second-biggest. The proportion of its population living below the World Bank’s extreme poverty line — US$1.90 per day in 2011 prices — dropped from more than 88 per cent to less than 1 per cent.

Those days have long gone. Between 2013 and 2019 China’s growth rate slowed to an annual average of 7.0 per cent, and since the end of the pandemic it has slowed further to an average of 5.2 per cent. That’s still impressive by the standards of Western countries and most “emerging and developing” economies — although it’s less than India (7.4 per cent), Vietnam (5.7 per cent) or the Philippines (5.6 per cent). And the IMF expects China’s growth rate to slow to just 3.3 per cent by the end of this decade.

To a significant extent, this slowdown has been, and will continue to be, both inevitable and inexorable.

China’s working-age population (fifteen- to sixty-four-year-olds) grew at an average annual rate of 1.3 per cent in the 1990s and 2000s but slowed to just 0.3 per cent in the first half of the 2010s. Since 2015 it has actually been shrinking — by an average of 0.2 per cent each year. That annual decline is expected to a peak at minus 1.5 per cent in the mid-2030s, according to UN projections. By 2050, China’s working-age population will have shrunk by almost a quarter from its 2015 peak.

Adding to the slowdown is a fall in employees’ average working hours from more than fifty a week between the mid-1970s and the mid-2010s to fewer than forty-six in 2023. As in many other countries, this is partly the result of an ageing workforce. But it also reflect younger workers’ growing rejection of what has come to be called China’s “996 culture” — the expectation, especially common in China’s tech sector, that people work from 9am to 9pm, six days a week — and a growing preference for what Xi Jinping and others have derided as “involution and lying flat,” or doing the bare minimum of work to get by.

One final cause of the downturn is a sharp slowing of the growth in labour productivity. From an annual average of more than 9 per cent between 1992 and 2012, the figure fell to 7 per cent between 2013 and 2019 and just over 4 per cent since the end of the pandemic. This partly reflects the near-exhaustion of the productivity gains from moving more than half of China’s workforce out of subsistence agriculture into urban jobs in manufacturing and services occupations, compounded by the inevitable shift from manufacturing to service jobs (where productivity typically grows more slowly than in manufacturing) as China approached “middle-income” status.

The effects of these shifts in the demographic and economic drivers of Chinese growth have been amplified by the protracted deflation of the property bubble that accounted for an outsized share of economic growth in the decade after the global financial crisis. China’s subsequent experience of persistent deflation — not just of property prices, but also of consumer prices and prices more generally — has much in common with Japan’s experience in the decades after the collapse of its property bubble at the end of the 1980s.

Like Japan, Chinese authorities opted to manage that process over an extended period to avoid an abrupt downturn of the kind experienced in the United States and several European countries between 2005 and 2009.

That concern about financial stability is also reflected in Chinese authorities’ reluctance to respond to the current slowdown with significant monetary or fiscal stimulus measures, in contrast to their reactions to previous economic downturns. China has a lot of debt — equivalent to 290 per cent of GDP as at March 2024, according to the Bank for International Settlements, compared with 146 per cent for the other emerging and developing economies in the BIS database and 265 per cent for advanced economies.

Also like Japan — whose debt-to-GDP ratio of 400 per cent is the third-highest in the world — China’s debt is owed to domestic financial institutions, particularly state-owned banks. But that still represents a significant source of risk to financial stability, especially if large write-downs in the value of bank loans to property developers were to coincide with doubts about the stability of China’s managed exchange-rate regime. High levels of debt can become particularly problematic during when a period of deflation increases both the burden of debt and the deflation-adjusted cost of servicing it.

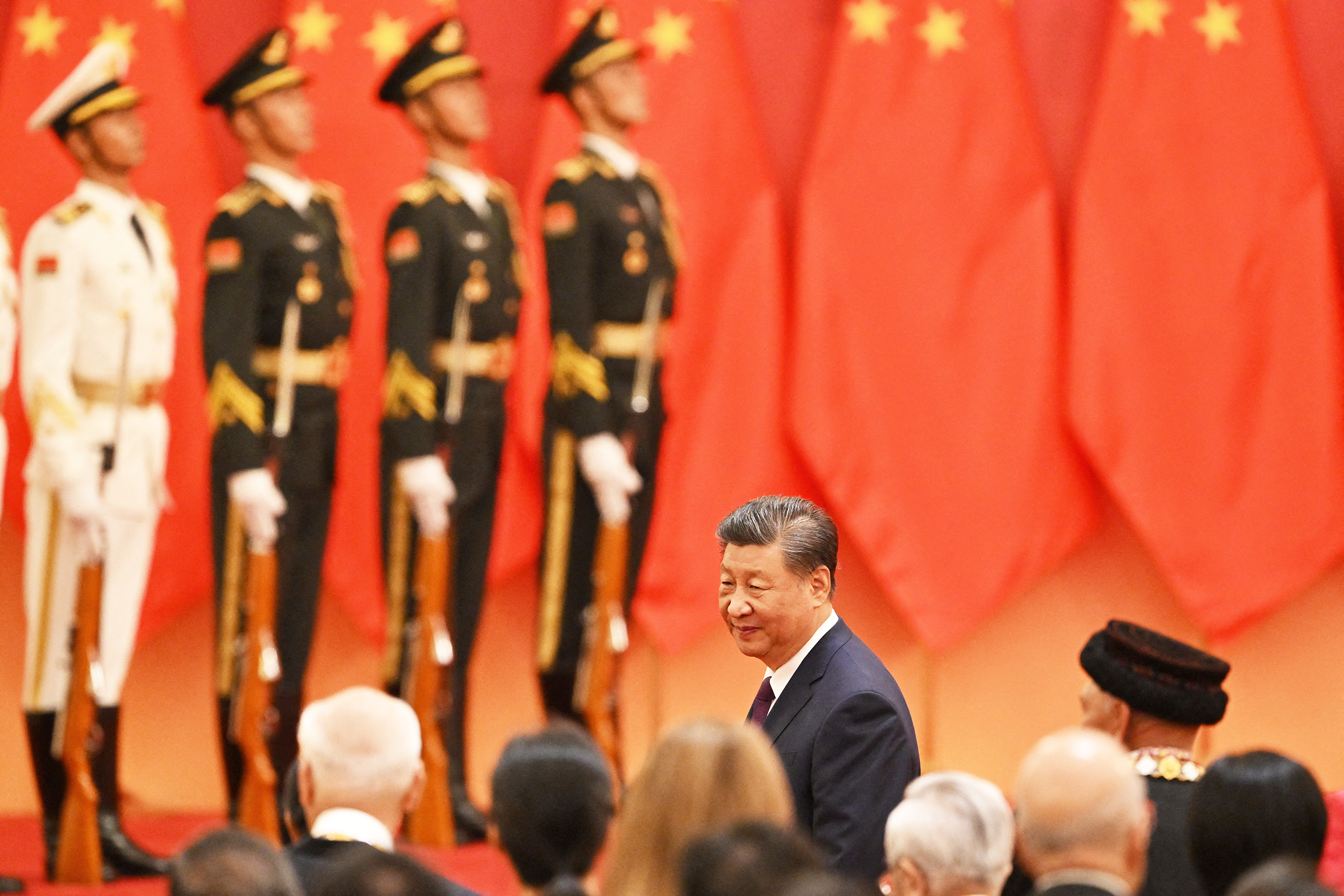

One other development over the past decade augurs badly for China’s longer-term growth. Since 2017, as Australia’s US ambassador Kevin Rudd shows in his recent book, On Xi Jinping, the Chinese president has “moved the centre of gravity of Chinese economic policy to the ‘Marxist left’ by asserting the primacy of state planning over market forces [and] the state-owned enterprise sector over private firms.”

State-owned enterprises have made a striking comeback under Xi’s rule. As of 2022, they totalled more than 27,000, an increase of 10,000 since 2011, their numbers having declined from almost 65,000 in 1998 under premier Zhu Rongji’s reforms. SOEs make consistently lower returns on assets and equity than private sector firms — and private sector returns have themselves been more than halved, due in part to Xi’s harsher regulation of private and foreign-owned businesses.

Added to heightened geo-political tensions, this increasingly hostile regulatory environment reduced foreign direct investment into China to less than US$1 billion in the year ended June 2024, far lower than the annual average of US$244 billion between 2010 and 2021.

It’s true that Chinese firms have continued to invest large sums abroad — averaging US$262 billion a year since Xi launched the Belt and Road Initiative in 2013, up from just US$53 billion a year over the previous decade — such that China’s foreign asset holdings now exceed its foreign liabilities by almost US$3 trillion. But China’s annual investment income deficits have exceeded US$100 billion in recent years, suggesting that these investments have been poorly allocated.

Indeed, although China continued to run merchandise trade surpluses of more than US$800 billion in 2022 and 2023, its overall balance of payments position is no longer as strong as it once was. Those surpluses are increasingly offset by rising deficits on services (especially tourism) as well as investment income. Immediately before the global financial crisis, China was running current account surpluses equivalent to more than 9 per cent of its GDP; in the year to June 2024, the figure was just 1.2 per cent.

And those large surpluses on merchandise trade owe more to sluggish imports than they do to burgeoning exports. Although China’s motor vehicle exports mushroomed to US$10 billion in the twelve months to September this year, its other exports have flatlined since 2022. Meanwhile the dollar value of China’s merchandise imports in the twelve months to September was almost unchanged from that of 2018.

Much-diminished current account surpluses combined with dwindling foreign investment inflows leaves China’s currency highly vulnerable. The value of the renminbi could fall abruptly if China were to experience renewed financial market turbulence like the mid-2015 shock, when the Shanghai stockmarket fell by 26 per cent in just over a month and then by a similar amount over the following eight months. The People’s Bank of China was forced to use almost a quarter of its foreign exchange reserves defending the exchange rate.

Chinese authorities responded to that turbulence by subjecting capital outflows to much stricter controls, which have remained in force ever since. They could conceivably engineer a large depreciation of the renminbi if Donald Trump again becomes US president and, as he has threatened, increases tariffs on all Chinese imports by 60 per cent.

If the Chinese authorities are serious about lifting China’s potential growth rate, the most obvious and sustainable move is to stimulate household consumption spending. Household spending of this kind adds up to just 38 per cent of China’s GDP, compared with between 52 per cent and 56 per cent in most other Asian economies and 61–62 per cent in Brazil, India and South Africa. It is the mirror image of China’s unusually high household-saving rate, which has averaged 31.8 per cent of household disposable income since 2008, up from 21.5 per cent over the previous two decades.

Chinese households save such a high proportion of their income because the country’s social security system is unusually thin, especially for an avowedly socialist system. According to World Bank data, China spends barely more than 1 per cent of its GDP on social assistance, compared with 1.6 per cent for Thailand and Vietnam, two Asian countries with comparable age profiles. For an overtly socialist country, China also makes remarkably little use of progressive taxation to fund social security transfers or other government expenditure.

The World Bank, the IMF and others have repeatedly urged Chinese authorities to demand a dividend from state-owned enterprises. The benefits would be twofold: it would impose greater discipline on SOE’s capital investment; and it would help pay for a more comprehensive social safety net. That more generous safety net would in turn reduce households’ imperative to save, and thus enable an increase in their consumption spending. But such advice has fallen on deaf ears.

The various monetary and fiscal policy stimulus measures announced over the past month appear directed more towards boosting confidence in the Chinese stockmarket than lifting consumer confidence, which is running at more than 20 per cent below the average of the three pre-Covid decades and shows no sign of recovering.

China’s leaders appear convinced their country’s future growth will be driven by two things: import replacement (which is what Xi Jinping’s “dual circulation” strategy appears to be about, not unlike the “industrial policies” being pursued by a growing number of Western nations), and “new productive forces,” ostensibly based on scientific and technological innovation.

More broadly, China’s economic plight shows the risks of elevating “security” above all other considerations, as Xi has done. All too often, those who specialise in proffering advice on matters of security seem incapable of ascribing probabilities of less than 100 per cent to the risks that concern them, and all too often they take the view that no price is too high to pay in order to reduce that probability to zero. Rarely are the measures recommended by security advisers subjected to any kind of cost–benefit assessment — even though their costs are usually very high — and almost never are they subject to any kind of external scrutiny.

China’s economy is now nine times as large (measured in US dollars converted from yuan at purchasing power parities) or almost fifteen times as large (measured in US dollars converted at prevailing market exchange rates) as it was when it joined the World Trade Organization at the turn of the century. Even as its growth rate slows further, it will continue to be the most important contributor to world economic growth for at least the remainder of the present decade, accounting for more than 20 per cent of the growth in global GDP from 2024 to 2029, according to the latest IMF forecasts, compared with 15 per cent from India, 12 per cent from the United States and 10 per cent from the European Union.

Most advanced economies are importers of commodities and exporters of manufactured goods, so China’s emergence as the world’s biggest importer of commodities and exporter of manufactures pushed up the prices of the things those economies import and pushed down the prices of the things they export, as well as displacing many of the industries that accounted for large shares of their economies. Australia is different: China’s economic development pushed up the prices of things we export and pushed down the prices of many of the things we import. These terms-of-trade gains have boosted Australia’s real national income by half of a percentage point per annum — or almost 40 per cent in total — over the past thirty years.

Australia is one of only seven “advanced” economies to run a bilateral trade surplus with China, and is surpassed only by Taiwan. We been among the biggest beneficiaries of China’s rapid growth and industrialisation since the early 1990s.

But those benefits come with a downside. If — as seems increasingly possible — China attempts to grab Taiwan, either militarily or through some kind of air and sea blockade, and the West responds by imposing economic and financial sanctions on China, no Western nation will pay a higher economic price than Australia. We would lose close to 8 per cent of our GDP overnight. Instead of worrying as much as we are about how dependent we’ve become on China as a source of imports — and kidding ourselves that we should replace them with stuff “made in Australia” — perhaps we should be thinking more about the consequences of having allowed ourselves to become as dependent as we are on China as a market for our exports. •