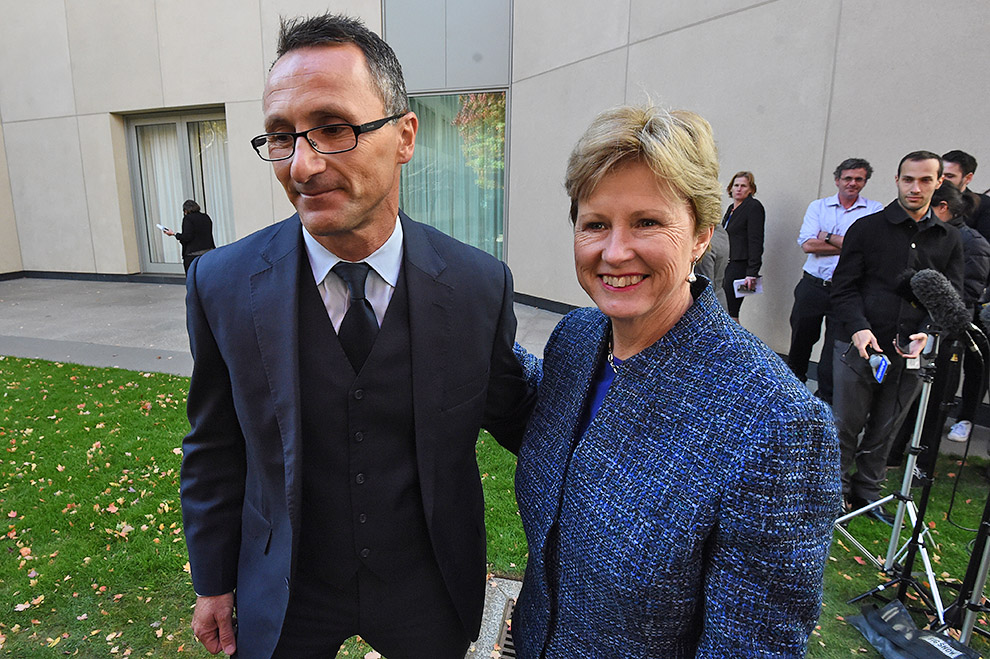

At his first press conference as leader of the Australian Greens, Richard Di Natale hinted that perhaps the party would be more centrist in future. If that means a Senate that is in any way more cooperative then that’s good news for the Abbott government. The Coalition plus the Greens form a comfortable majority in the chamber.

Like all political parties, the Greens frequently receive helpful strategic guidance from opinionistas who would never dream of actually voting for them. The advice is generally along the lines of “behave more like a party I would support,” and in the Greens’ case it’s usually that they should be more moderate, sensible and cooperative.

If the minor party’s goal is to become a major one, as is sometimes claimed, and to overtake, or at least rival, Labor as the nation’s major left-of-centre party, then such an approach would be sound. But if you believe that’s a pipedream – that the only realistic goal is to retain a large presence in the Senate, keep the electorate of Melbourne and perhaps grab one or two others – then being more like the big players is not necessarily in the party’s interests.

In this way the Greens differ from the Australian Democrats, whose success did depend on floating around the “middle” and compromising between the big two.

Just like the major parties, the Greens are self-interested and calculating – and, as we saw yesterday, partial to employing talking points. The party’s position on asylum seekers – which is to end mandatory detention and offshore processing and put in place a “regional solution” – doesn’t stand up to scrutiny if its aim is stopping the boats. But it contrasts sharply with the major parties’ and that’s enough for a sizeable minority of voters. Greens supporters aren’t alone in voting with the heart more than the head.

That issue, unauthorised boat arrivals, is a chief component of the Greens’ electoral support. There were Greens Senators before 2001 (see my electoral history of the party) but the federal election in that year saw a dramatic increase in support. From a House of Representatives vote of 2.6 per cent in 1998, they jumped to 5, and what took them there were the twin causes of asylum seekers and Australia’s participation in the invasion of Afghanistan. On both they deemed Labor under Kim Beazley too similar to the Coalition. Most of their new votes were former Labor ones.

If not for these two events, would the Greens have eventually achieved this success anyway? Who knows? But the importance of leader Bob Brown’s public persona is probably less contestable. For many years, to most Australians, he was the Greens.

That 5 per cent (and 4.9 per cent in the Senate) seemed very impressive thirteen years ago – about as high as a party like that could expect to go. But support rose again in 2004, then in 2007, and peaked in 2010 at 11.8 per cent in the House and 13.1 in the Senate. After 2011 it began to slide – first, when Brown was still leader, at the 2012 Queensland election, and then under Christine Milne.

But something else started happening: they began winning lower house seats at general elections. At the height of the party’s popularity, in 2010, Adam Bandt won Melbourne thanks to Liberal how-to-vote cards recommending him ahead of the Labor candidate. In 2011, Jamie Parker took Balmain at the NSW state election. Then, in 2013, Bandt easily survived despite Liberal how-to-vote cards favouring Labor. (Had the Liberals done that three years earlier, Melbourne would have stayed in Labor hands.)

And over the last seven months, at the Victorian and NSW elections, the Greens have taken lower house seats despite little (in Victoria) or no (New South Wales) increase in statewide support and unfriendly Liberal how-to-vote cards in Victoria. At both elections their support receded a little generally but skyrocketed where it mattered. Time will tell how much of this reflects a considered strategy and if it can be replicated.

Climate change is, of course, the other plank in the party’s support. This week the accusation has been levelled again that, if not for the Greens, Kevin Rudd’s carbon pollution reduction would have been legislated in 2009 and become operational in July 2011. This involves a large dollop of misremembering.

First of all, Labor plus the Greens never had a Senate majority under Rudd. For the package to pass it would have needed the votes of the Greens plus Nick Xenophon plus Family First’s Steve Fielding – an all-but-impossible feat given Fielding’s climate change scepticism. This might help explain why Rudd never bothered engaging with the Greens.

In early December 2009, just after the Liberals had replaced Malcolm Turnbull with Tony Abbott as leader, the legislation was voted on in the Senate, and Liberal senators Sue Boyce and Judith Troeth crossed the floor to support the government. If the Greens had also voted in favour, it would have passed.

But would the Liberal pair have voted that way if it had meant the legislation becoming law? Their party room had just taken a decision to elect a new leader whose strategy for the next election largely revolved around opposition to Labor’s emissions scheme. It’s one thing to cross the floor as a symbolic act of defiance, another to demolish your party’s plan for election.

We’ll never know, but it’s at least open to question.

After she replaced Rudd and scraped back to office in 2010, Julia Gillard made a serious mistake by signing, with great fanfare, a deal with the Greens. It was unnecessary because Bandt had promised during the campaign to support Labor in the event of a hung parliament. The following year, allowing the carbon price scheme they forced on her to become known as a “tax” was another A-grade blunder. (It, like Rudd’s scheme, was an emissions trading scheme with an initial fixed price.)

The “t” word was favoured by Brown, possibly to differentiate the scheme from Rudd’s (and maybe that’s why Gillard didn’t object to the terminology). And when the bill passed parliament, the Greens popped corks and boasted that it would not have happened without them. The Coalition couldn’t have put it better themselves. In driving such a hard bargain for their support in the House of Representatives, the Greens greatly damaged the Gillard Labor government.

You can’t blame them. They behave in their own perceived political interests. Just like all the others. And so far it’s worked pretty well. •