In early January I asked a couple of old friends to help me think my way back into the magazine industry. I sweetened the deal by offering to cook, which was the least I could do. There was a lot of ground to cover.

It wasn’t that I’d gone into snooze mode over Christmas and New Year and needed a quick reboot. It had been years since I’d paid close attention to what was happening in magazine publishing. I’d taken my get-out-of-jail-free card and shot through to another life. It’s a common-enough story among journalists of my generation. In my case, I accepted a redundancy from the Bulletin in 2006, and in May 2009, after one last glorious assignment for Australian Geographic, I said I was going sailing. People say that all the time, but that’s what actually happened.

But the sailing was over and now, out of the blue, had come a commission that invited me back on my old turf to look at the woes of Bauer Media and more generally to consider the state of magazines. I doubt there has ever been a trickier time to delve into this topic but I told myself, in my Protestant way, that this would be good for me. It would force me to take a measure of myself.

I’d ride out a force eight gale any day over working in magazines again. I know my limits. But since that long summery lunch, when I engaged my friends Kathy Bail and Bobbi Mahlab to take me through a professional warm-up routine, I’ve made up a fair bit of ground, and covered some more. (It is humbling to realise how much of a habit thinking is, and how quickly you can lose it.)

What follows is far from complete, but I’ve drawn pleasure from reconstituting myself as a magazine writer. Pleasure is not incidental to this story, by the way. Magazines are a business and, under the normal rules of engagement, they need to keep turning a profit for their product to survive. Everyone knows how hard it is to get people to pay for information now. They will pay for pleasure, though, which is the most promising way for magazines to find an edge. Or it may be that the normal rules of engagement will not prevail. Who knows?

I had a few lucky breaks in journalism over the years, but the luckiest was the timing of my exit. By complete chance, I avoided the worst of the trauma that began to break over Australian Consolidated Press, or ACP, after the death of Kerry Packer in December 2005 and has not let up since.

Of course, I shouldn’t pretend that the end of my three-decade career came as a complete relief. My identity was tied up with being a journalist, and letting go wasn’t as painless as banking the redundancy payment. What helped most was getting out of town, a long way out, on a boat.

This isn’t the place for recounting tall tales about the sea. What’s relevant is how being a sea nomad for several years affected my knowledge and understanding of how magazines were facing down the perfect storm brewed by tech and telephony. By magazine, what I mean, at least to begin with, is the printed product with its distinctive heft and touch, the treat you look forward to taking on a plane or to the beach or curling up with on a couch after work.

I’d stopped writing for magazines, but I hadn’t stopped wanting to read them. On our first voyages to the tropics on our boat, my husband Alex (also a big reader) and I were on short rations in the magazine department. But in 2010 Apple launched its iPad and by early 2011, when we were preparing for our second and more ambitious voyage, magazine publishers were offering apps for tablets. We bought an iPad mainly so we could pick up our digital subscriptions to the Economist and the New Yorker while we were afloat.

We spent nearly five years cruising and crossing oceans, and though we were frequently off the grid, we didn’t miss an issue of either magazine. Every time we found a free wi-fi connection, we’d download the backlog (and pick up emails, post our blog and so on). On remote atolls, where internet service is fragile, that process could take several hours and involve many beers, but so be it.

The publishers of these two magazines were among the first to adapt their print format to the tablet, and they did it well. I shifted gratefully into reading on a screen. Who doesn’t enjoy opening the New Yorker cartoons anywhere at any time, but especially after a four-week passage from Panama to the Marquesas?

In March 2016, we put the boat up for sale in New Zealand and came back to our house in Sydney. We didn’t bother downloading digital issues any longer, even though we now had cheap, fast and unlimited internet. One of the pleasures of having a fixed address was having magazines come through the letterbox again. Sometimes there’d be a long wait then a pile-up in the post, but I didn’t mind, and still don’t. I don’t read magazines for news anymore — who does? And there is still, for me at least, excitement in tearing open the wrapping… all that tactility.

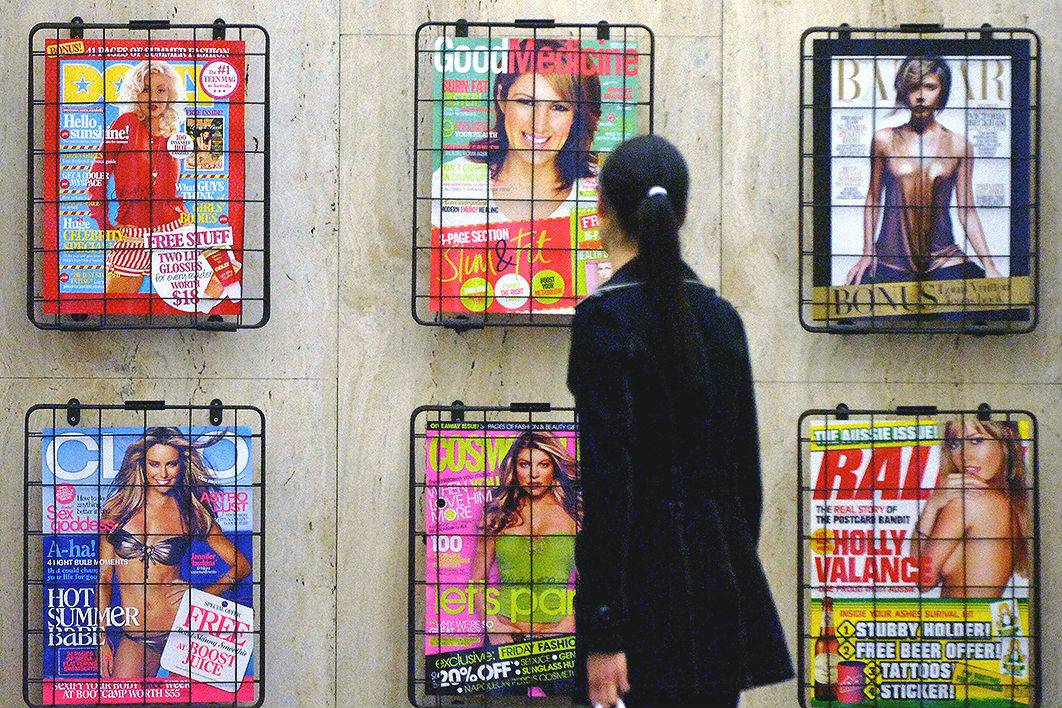

In the euphoria of being back among print and paper, it took me a while to notice how much thinner the selection of magazines had become, especially in newsagencies that had always carried a decent range. Instead of aisles of titles, the magazines were pushed against a back wall. And what was there didn’t grab me as much. That was the strangest part.

If I scroll back to my working life, choosing a magazine had never been a problem. At an airport, for example, nine times out of ten I’d have reached for a glossy — Vanity Fair, American or British Vogue, or even Tatler in its heyday — and known it would hit the sweet spot. I’d get my fix.

But now, in the same situation, I floundered. More often than not, even having got down on my haunches to check the lowest shelves, I’d end up walking out empty-handed.

The first few failures to scratch my old magazine itch rattled me. From what I could see, magazines hadn’t changed that much. Must be me, I figured. My interests had drifted, of course. And I was old (well, getting older). Perhaps I was just over the glossies. It happens.

Of its time? The final edition of the Bulletin on sale in late January 2008. Shannon Morris/AAP Image

But it wasn’t just me. What I was seeing — or rather, not seeing — spoke to a profound disorientation of the culture. My own maladjustment probably didn’t help. Dazed and confused doesn’t begin to describe those early months living back in the city.

I wasn’t a complete Luddite. I’d managed to work out how to make regular blog posts even from the middle of the ocean. I was familiar, theoretically, with notions like disruption and streaming. But ironically the one word I’d failed to register the significance of was “mobility.”

The smartphone revolution had begun for real while I was preoccupied with peripherals like weather systems and sea state and how much anchor chain would keep a twenty-tonne boat from dragging in a deep Pacific anchorage. Meanwhile, back home and all over the world, people had begun carrying their lives in their pockets.

Global smartphone sales advanced fairly slowly from the launch of the iPhone in 2007 until 2009, but from 2010 sales began to pick up serious momentum, with the biggest surge between 2011 and 2013. In most advanced markets smartphone penetration is heading for between 80 and 90 per cent this year. Mobile internet use has doubled since 2011, and is expected to account for three-quarters of online use by 2019. “For most consumers and advertisers, the mobile internet is now the normal internet,” Jonathan Barnard, head of forecasting at media agency Zenith, has said.

That story is backed in Australia by the 2017 Sensis Social Media report, which found smartphone penetration above 80 per cent, and rising, while use of laptops (59 per cent), tablets (45 per cent) and desktop computers (51 per cent) was falling. Smartphones are by far the most common way that Australians access social media and, just to end this drum roll of statistics, eight out of ten Australians use social media.

It wasn’t just the internet that kneecapped traditional magazine businesses; it was the smartphone and Facebook. It’s a chicken-and-egg thing, but the huge uptake of smartphones triggered a stampede towards social media with its myriad communities. Until then, people had found and demarcated their tribes in all sorts of different ways, but magazines were an important one. People gravitated towards magazines as much to endorse their idea of themselves as for information and entertainment, as ex–British Vogue editor Alexandra Shulman wrote on Business of Fashion. “You chose to be seen with Vogue instead of Cosmopolitan, with World of Interiors instead of House Beautiful, with Grazia rather than Hello. Or vice versa.” Now, through Facebook groups, Instagram, Twitter feeds and the like, there are easier and cheaper ways of achieving many of the ends that magazines once served. The consumer magazine market is “reaching an existential threshold” and publishers “face a crisis of purpose,” London-based media research group Enders Analysis warns.

Print is far from dead, but the analysts and consultants are having a field day. Data is cut every which way. There are summits and reports galore, mostly forecasting more pain ahead. You’ve heard it all before. The old business model is shot. The ads have gone elsewhere, and the expectation that everything you read online should be free is proving difficult to dislodge. Magazine circulation (where it’s still counted) and readership slide month by month, particularly among mass-market magazines that, as London-based media consultant Colin Morrison recently tweeted, “still shout the loudest, even in free fall.”

It all happened so quickly, didn’t it? One moment we were paying the extra for our airfreighted copies of Vanity Fair and the next we were mourning the passing of the golden age of magazines that Tina Brown documents in her Vanity Fair Diaries. When Condé Nast owner Si Newhouse and Playboy founder Hugh Hefner died within a week of each other last October, the Financial Times ran what was effectively an obituary for the glossy era. The balance of power between technology and media had “shifted irrevocably,” the FT pronounced, and the question was how long magazine publishers would survive the new era.

And so to the Bauer Media Group, Europe’s largest magazine publisher, which bought ACP in September 2012, and may now regret it ever set foot down under. May regret, I stress, because the Bauer family, which has managed the company for five generations, rarely makes statements about its business. The local boss of Bauer in Australia, Paul Dykzeul, doesn’t have a problem with that. “The Germans are intensely private, and so they should be,” he told me. “[The business] is theirs.”

Even when the news is good, the parent company releases results infrequently, with a minimum of detail. In September 2016 the company revealed that for the fiscal year 2015 it had posted a turnover of €2.3 billion (A$3.6 billion), the second-highest in its history. Classic (aka print) magazine sales showed a gentle downward trend over the previous two years, but in 2015 still made far and away the greatest contribution to the group’s turnover, with sales of €1.3 billion. The company is active in twenty countries and sales outside Germany that year accounted for two-thirds of total turnover. In Germany, Bauer published twenty-seven of the top one hundred magazine titles. “Print is the platform for our success,” publisher Yvonne Bauer said at the time. The group’s digital division accounted for €122 million of turnover and achieved 16.2 per cent growth. This, as far as I can establish, is the most recent public statement from Bauer Media Group on its financials.

For the sorrier story of its Australian business, I rely on reporting from the Sydney Morning Herald. In December the paper’s Colin Kruger got hold of the most recent financial accounts lodged by the local arm of Bauer Media for the financial years 2014 and 2015, and wrote that they showed reported losses of $116 million and liabilities exceeding current assets by $51.6 million. The local operation was kept afloat by a $30 million loan from its German parent, Kruger reported. Dykzeul responded by saying that the company was private, and did not comment on its financial business.

Upbeat: Bauer Media’s Australian head, Paul Dykzeul. Supplied image

In February, I got in touch with Colin Morrison, whose blog Flashes and Flames tracks the fortunes of global media companies. I recognised his name from the old days. Morrison once sat in the seat that Dykzeul now occupies. He ran ACP for Kerry Packer from 1995 to 1999 but he’s also been CEO of media companies owned by Hearst, Axel Springer, Future, EMAP and others. These days he holds no executive role, though he’s involved in various digital media and information companies. He sees the big picture.

Bauer, he tells me by email, is a rich and profitable company with a strong track record over the past thirty years in Germany, Eastern Europe, Britain and the United States. It is clearly shocked by its experience with the former ACP. “There is no doubt that Australia has been a very cold shower for a company which is simply not used to getting it so wrong,” writes Morrison. But he cautions against assuming the company is terminally lost down under. The Bauer family, he says, has built its global media business by being patient and long-term. Indeed, he says, if his old boss Kerry Packer were still alive, he wouldn’t be finding it easy either. But nor, he adds, would KP be feeling sorry for himself as some of his successors have been doing in the past twelve years. “He would be noisily in hot pursuit of a new long-term strategy without worrying too much about the short-term distractions of declining revenues. Salami-slicing costs and tweaking teams and business models is no substitute for a real plan. That’s the message for Bauer.”

The short history of how Bauer Media came to own ACP goes something like this. In 2007 James Packer sold his media interests, which included the Nine Network and the magazines, to the private-equity company CVC Asia Pacific for around $5.3 billion. A critical detail of the deal was that rights to the digital content of ACP titles would be held by Nine’s digital arm, Ninemsn. Later, when the print magazines were sold off separately, this became a significant problem for their new owner.

CVC’s investment in Nine Entertainment did not turn out well, not least because in 2008 the global financial crisis hit and advertising revenues tumbled across all media — but also, for those who could see it, because the smartphone had begun its rampage. CVC became desperate to off-load its media assets, and in September 2012 it found a buyer for ACP. Bauer Media paid approximately $500 million to enter the Australian and New Zealand markets.

At the time, some people thought they’d paid too much; others believed they’d picked up a bargain. Nobody can say, except the Bauers. There was certainly much trilling about the fact that this was a family-owned company — and “not somebody who is only intent on buying into the company to make money,” as Ita Buttrose told the Sydney Morning Herald.

But still, $500 million isn’t chickenfeed. ACP represented Bauer’s largest investment since late 2007 when it had paid more than £1.1 billion for EMAP’s radio and magazine businesses in Britain. It was also the first major roll of the dice for Yvonne Bauer who, barely twenty months earlier, had been anointed by her father Heinz (over her three sisters) as his successor. The chosen Ms Bauer, then in her mid-thirties, was jubilant about her company’s expansion, and a month after the ACP deal was clinched she launched a new slogan: WE THINK POPULAR. She came out to Australia in February 2013, gave unprecedented interviews in which she emphasised Bauer’s commitment to and love of print, and that’s where things started to get interesting.

Before Inside Story contacted me, I’d heard a little about Bauer Media from the few people I came across socially who were still involved with the company. “The Germans” (as everyone called them) weren’t easy to work for, they said. The years of private-equity ownership hadn’t been a walk in the park, but when Bauer came to town, everything changed overnight. There was a cultural mismatch between Hamburg and Sydney. Bauer had a different management style (the family is notorious for micromanagement) and didn’t understand how to sell the magazines they’d bought. Right from the start there had been pushback from the local staff, who fought for their own ideas. The Germans didn’t understand that either. They were used to their editors doing what they were told.

People weren’t happy, that much was obvious — though frankly, people were often not happy during my fourteen years of working at ACP, even when the place was buzzing and its “iconic” magazines were making money hand over fist. The culture was awash with anxiety. But things were now much grimmer. In every traditional media company people feared for their jobs, but at Bauer expressions of fear and pessimism were amplified.

The company couldn’t keep out of the news. Mumbrella, the media and marketing industry news site, has been tireless in its reporting of the “nightmare” at Park Street (as Bauer headquarters in Sydney is known). Fairfax columnists, some of them ex-Bauer themselves, have kept close tabs on the carnage too, building a dossier of the closure and sale of magazines, the sudden resignations of popular editors and unexpected departures of executives, the forming and dissolving of divisions and partnerships and, most diligently collected of all, the churn at the top. Five CEOs in the past six years. That’s a company in shock, as Morrison says.

And then there is the trouble with Rebel. Last year’s $4.5 million defamation win by actor Rebel Wilson was a huge story. On 8 March she announced she wanted Bauer Media to pay a further $1.3 million to cover her legal costs. (Bauer’s appeal against the amount of the damages is due to be heard in April in the Court of Appeal.)

It’s a humid and grey Tuesday afternoon when I go in to Park Street to meet Paul Dykzeul. The front foyer, which I remember as a thoroughfare for loudmouth sexy young women and big-swinging-dick types, is deserted. I wondered how many of those women have moved over to Surry Hills to work for Mia Freedman, who was the epitome of the company It Girl when she became the youngest-ever editor of Cosmopolitan in 1996. Freedman’s immensely popular digital women’s network Mamamia, which evolved out of a blog she began in 2004, is something Paul Dykzeul frankly envies. “It’s bloody brilliant,” he tells me. “I just wish I’d thought of it.” I believe him. Bauer’s own digital network, Now to Love, is a work in progress, to put it kindly.

Dykzeul (Mr Dykzeul to his German colleagues, who prefer formality in both dress and form of address) sees me in his office on the third floor. That’s the floor where Kerry Packer held court, and it still holds the Packer imprint. Dykzeul is another kind of man altogether, slightly built, nervy and — as I discover over the course of an hour’s conversation — astonishingly cheerful given the nature of the job he’s been handballed. (When I mention this to a mutual Kiwi friend, NZ Life & Leisure editor and publisher Kate Coughlan, she replies, “Paul is wonderfully upbeat like our prime minister, ‘relentlessly positive’ — maybe it’s in the water.”)

Dykzeul was running the New Zealand end of things for Bauer when he was called back to Sydney last June to replace Nick Chan, who had lasted only a year as chief executive. Chan had replaced David Goodchild, a Brit who didn’t ever make Sydney his home, and Goodchild had replaced Matt Stanton, who’d led the company through the first two tumultuous years of Bauer’s ownership and then left at the end of 2014 to work for Woolworths. Dykzeul, who is sixty-five, wasn’t busting to be Bauer’s next Australian CEO. He had settled back in Auckland after spending many years in Sydney, and was doing a good job for Bauer there, from several accounts. “I needed this like a hole in the head,” he says.

Coughlan thinks the Australians are “bloody lucky to have him,” but Bauer’s internal appointment didn’t set the Sydney media alight. Mumbrella called it uninspired, which seems to have hurt. “You can call me anything but don’t call me dull,” says Dykzeul. He also takes umbrage at the persistent criticism that Bauer cops from other media. The attacks on its performance are “so dumb and ill-conceived that I shake my head in disbelief,” he tells me. He maintains that a lot of the damage to the company’s business was done during the CVC period. “People say Bauer have done it, which is an extraordinary leap, based on complete ignorance of the position.” Moreover, he says, if ever there were a time for media companies to stand together and be proud of what they do, it’s now. (A month later, when six major media companies announce they’ll support Bauer’s appeal over the amount of the Rebel Wilson payout, I find myself wondering if Dykzeul’s wounded feelings are mollified.)

So why did he come when the Bauers whistled? He’s loyal, that’s why. To the magazine industry in general but to ACP (and, because of the changing circumstances, to Bauer) in particular. He got his start with ACP in distribution and worked his way up through management ranks. At one point he worked for the competition (Murdoch Magazines, Pacific) but he came back to ACP. “I love the company,” he says. “I’m not talking about loving the Bauers… I thought the challenge of trying to put the business back on an even keel, of plotting a path forward, was not too much for me to take on.” He seems to search for the right way to say this. “I would rather that people thought of the company…” He pauses. “In some ways I wish it wasn’t called Bauer.”

But it is, and Morrison thinks that Dykzeul — “the cheerful, practical, no-nonsense guy” — might be the one the Bauers have been looking for all along, the one who will stabilise their business in Australia “as long as he is given the freedom to rationalise the business on the way to developing truly versatile media brands.”

Since his arrival, Dykzeul has slimmed down the executive team (“the business couldn’t afford the structure it had”) and not only closed four consumer titles, including Yours and Men’s Style, but also pulled the plug on Bauer’s custom-publishing business. Just recently he sold yet another of Bauer’s smaller titles, Australian Geographic. “We have tried that stuff, and we are terrible at it. Big companies cannot publish niche titles in my view.” (Bobbi Mahlab, one of my lunch companions and a custom publisher herself, offers the opinion that Bauer didn’t recognise where the jewels were — “the whole world has gone niche,” she says.)

What Bauer is hanging onto are mass-market titles, including Woman’s Day and the Australian Women’s Weekly which, in its heyday, was famously the most widely read magazine in the world on a per capita basis. With the Bulletin gone, the Weekly, founded in 1933, is the oldest magazine left in Australia.

Personally, I’m not heavily invested in whether the Weekly has a future. My mother didn’t read it, and nor do I, though I believe I missed a time when I might have. I’ve heard it said that Helen McCabe, who was editor-in-chief for six years from 2009, published some great covers. When she left suddenly in January 2016 she said all the right things, then resurfaced six months later at Nine Entertainment as head of lifestyle, and is now Nine’s digital content director. She’s preparing a new subscription site, Future Women, aimed at professionals and entrepreneurs — “a highly attractive female premium advertising demographic,” as she says. The content will be longer-form and “curated.” McCabe’s obviously still in the magazine business, but without the “legacy” millstone around her neck.

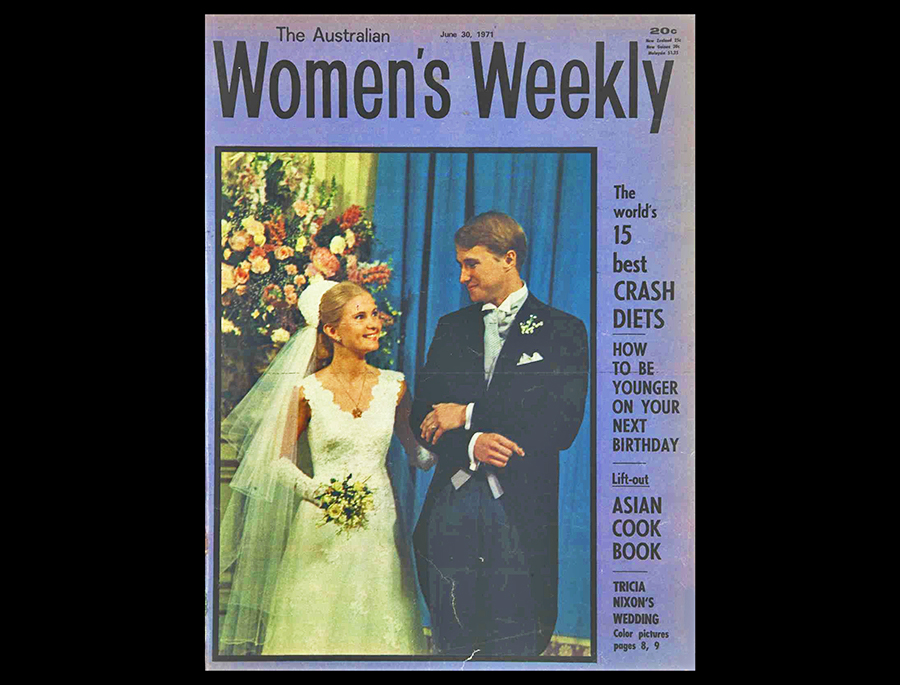

Bauer has appointed two new editors to the Weekly since McCabe’s departure, most recently Nicole Byers, who came to the magazine in July after seven years at the helm of OK!. She’s bagged the Prince Harry–Meghan Markle romance and the magazine has a discrete section for the royal engagement on its website. By chance, I have an old copy of the Weekly at home, dated 30 June 1971 (my artist daughter found it at a local market and was going to use it for collage). In that issue, the bride on the cover is American royalty, Richard Nixon’s elder daughter, Tricia. What knocks me for six is not how much has changed in the magazine in forty-seven years, but how much has stayed the same.

Page image from the National Library of Australia’s Newspaper Digitisation Program

Timeless: the Australian Women’s Weekly’s 31 June 1971 edition. Trove

When Dykzeul assures me that the Weekly is “still one of the great cornerstones of the publishing industry in Australia,” I am reminded of the swanky party that ACP threw for the 125th birthday of the Bulletin, where similar kinds of things were said about that “iconic” magazine. Three years later it was gone, closed by the accountants at CVC, who obviously did not see any future in the brand.

Even after an hour’s conversation with Dykzeul I’m not clear what he plans to do next with the Weekly. He tells me it has “years and years to go… and it is under no pressure.” He uses the word iconic. He also says the Weekly is “socially extremely important.”

I refrain from telling him that a man further down the line but closer to the market than him, a newsagency owner in Victoria called Mark Fletcher, has told me that the magazine looks “lost.” Fletcher also writes a very lively blog for newsagents, and is a software developer for newsagency businesses. He gets to see a lot of magazines, though like all newsagents he sells many fewer than he’d wish these days. He feels a strong residual loyalty to the Weekly, but from what he sees its audience has changed and left the magazine behind. “If I was influential at Bauer, I would say that the magazine needs to be exploded and dramatically altered for it to have a future beyond 2018.”

Several weeks later, Bauer Media launches a Female Future strategy that pledges, among other things, to publish ten million words about women across all its platforms before 2019. Dykzeul tells the breakfast audience of marketers and the like that Bauer Media’s “understanding of what women think, feel and want is unmatched across the publishing industry.” I remain underwhelmed. What is the meaning of all those words? (At least Dykzeul speaks plain English, unlike Melissa Overman, executive editor of News Corp’s freshly minted women’s site, the With Her in Mind Network, or WHIMN, who struggled to do so in an interview with Mumbrella: “Next year is really trying to understand the female digital consumer and what drives her to purchase products, or consume content, and then making sure we are innovating for that.”)

The Weekly’s star shines much less brightly than it once did, though independently audited circulation figures are no longer available. Bauer pulled out of the Audited Media Association of Australia in December 2016. News Corp and Pacific Magazines followed shortly after, arguing that circulation stats don’t recognise online and mobile readers or, as News Corp’s (then) chief digital officer Nicole Sheffield phrased it, no longer reflect the breadth or depth of the “brand reading audience.”

The latest magazine readership stats I can find were released on 9 February. They show print readership of the Australian Women’s Weekly down by 7.7 per cent in the year to December 2017, about the same decline as Better Homes & Gardens. Survey company Roy Morgan put a positive spin on the release — fifteen million Australians read magazines across print and online, it headlined. That’s a big figure, but it doesn’t speak as loudly as a figure published a week later: the first lot of Standard Media Index, or SMI, data for 2018 shows a 42.5 per cent decline in ad bookings for print magazines in the year from January 2017, with magazines’ digital properties also suffering a 40.5 per cent decline in the same period.

I read this after I’ve met with Dykzeul. That news was worse than the earlier SMI data I’d put to him, to which he had countered that the SMI doesn’t reflect the direct revenue from clients, small agencies and PR organisations that is now “a significant proportion of revenue.” When I ask exactly what the proportion is, I get no further response.

I don’t press Dykzeul unduly over Bauer’s stop–start progress into digital either. If Pacific wants to trumpet about outpacing Bauer Media’s digital performance “for the first time,” as it did just before Christmas, well, it’s still early days for everyone in the digital journey, as even Pacific admits.

Dykzeul says that if digital “migration” is not happening at Bauer as fast as he’d like then the same goes for everyone. “A lot of the big publishing companies are not that much more advanced than we are in this space.” He confirms that Bauer didn’t exit the deal that had locked up digital rights of magazine content within Ninemsn until June 2015 and that Pacific Magazines got out of a similar deal with Yahoo at about the same time.

None of this is very long ago. Time moves so fast in a digital world and I recall what Mahlab told me over lunch: Bauer didn’t move fast enough, but even the groups that did move early into digital publishing didn’t know how to make money out of it “because the revenue isn’t there.”

In a digital world, with its emphasis on content, Morrison explains to me, the large company has to work hard to build any kind of competitive edge. The economies of production, distribution, sales and marketing have all been undercut. “That’s why all over the world magazine companies are changing ownership.” For the large companies, he believes, the future is likely to be much leaner. They won’t own nearly as many titles, and they will concentrate on key brands that can become much more than magazines.

Brands, brands, brands. It’s how the future is configured. When Morrison talks of the “sheer untapped power” of the Weekly, he’s imagining how, based on its decades of selling millions of cookbooks, the Weekly might put its name to a range of high-margin products and services. He cites as a model for this kind of diversification the Weekly’s major competitor in the Australian market, Better Homes and Gardens. BHG is owned by Meredith Corporation, an Iowa-based publisher that about twenty-five years ago came to an agreement with Walmart to stock branded BHG products in its homewares and garden centres. Today Walmart stocks around 3000 BHG products in more than 4000 stores and online, according to Morrison; and on the back of this single monthly magazine, Meredith is second only to Disney in global licensing. And though you may not recognise its name or its other titles, Meredith has just bought Time Inc.

Kathy Bail, my other lunch companion, tells me she doesn’t think Bauer has an executive team that “knows how to maximise the power of [its] brands across different platforms.” Bail is usually very diplomatic, so I suspect she knows more than she’s letting on. These days she runs UNSW Press but she’s spent a lot more of her working life editing magazines. (I worked under her for seven years at the Bulletin.) She’s one of the smart ones who saw the future before it arrived at ACP. In 2006 she put up a blueprint to management for a different way forward for the Bulletin. She wanted to take it away from news and capitalise on its rich historical and literary associations (anybody think the New Yorker doesn’t do that?). Nobody wanted to know. She’s philosophical about that now. “Magazines do have eras, and sometimes time’s up.”

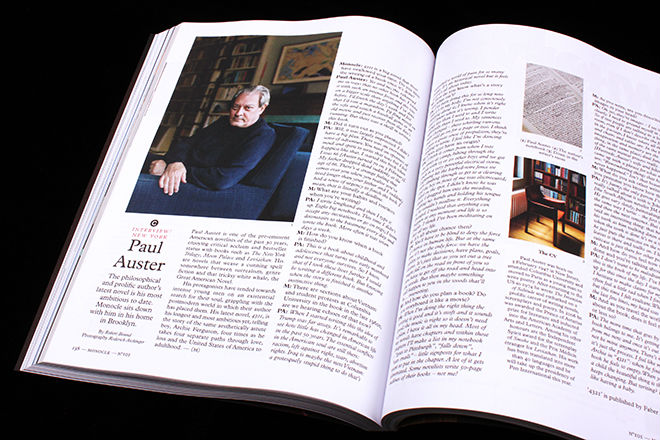

Brand conscious: Monocle magazine’s recent redesign. Magculture

And sometimes their time arrives. Recently I read about a magazine called The Party Next Door, which is presented like a twelve-inch vinyl record, with an inner sleeve and a gatefold outer sleeve. The Party Next Door is an extreme example of the kind of magazine I was hinting at when I said that perhaps there might be a time when the rules don’t apply. Mahlab had suggested as much to me. “Because there isn’t a commercial model, non-commercial models are springing up.”

The indies are hiding in plain view. You may have seen some of the bigger titles, like Apartamento or Kinfolk or Cereal or The Gentlewoman for sale in bookstores or cafes or art galleries or hipster clothing shops. I doubt you will have come across 032c, or Anxy, which won launch of the year at last year’s Stack awards, but you may well have seen some of the Australian indies that have made the Stack award shortlists: Dumbo Feather, The Lifted Brow, New Philosopher or Womankind (the last two out of the same pod in Hobart).

This is the countercultural magazine movement, a deliberate and slow form of magazine publishing that rejects and in some cases actively agitates against mainstream media values. The British magazine Delayed Gratification, for example, prides itself on being “last to breaking news.”

I can lose myself for hours in these beautiful products. They are carefully printed on delectable paper, and feature smart writing, stylish photography and a purist design ethic (always). Some appear monthly, but more are quarterly or even biannual. They shun news and celebrity and rely on social media to spread the word. They have websites, but the physical magazine is the thing they treasure. Some, like Womankind, deliberately don’t carry advertising. Others carry “partnered content” or “native advertising” (that’s a whole other subject).

Megan Le Masurier, a Sydney University media academic who has been researching indies for ten years, says she doesn’t think there is one indie magazine that survives on the cover price alone, though cover prices are comparatively high. Hardly any make enough money to pay their makers, who generally have day jobs. “Some of them are so idealistic it breaks your heart,” she says.

She is not being condescending. There is a chance that one of these small titles might become the next Frankie magazine, or thinking bigger, the next Dazed and Confused, the British fashion and culture magazine founded in 1991 by Jefferson Hack and the photographer Rankin. Dazed and Confused has not only survived the digital firestorm, but in its latest manifestation as Dazed Media has teamed up with Chinese luxury publisher Modern Media to form a new network, Modern Dazed. Hack is its CEO. Modern Dazed is the new home for Nowness, the video channel screening arts and culture that Hack founded in 2010 in conjunction with luxury brand conglomerate LVMH. You could never accuse Hack of being stuck in the past, and yet when he talks about the community-based culture of magazines, he sounds positively artsy.

Hack goes back to the ancient Greek root of the word, which means a container or storage unit, and from there surmises that a magazine can be in any format. “It can be a shop, a club, it can be in print, it can be people, or a city… As long as that container of knowledge is something that is accessible, and you’ve got that ability to step into it as an audience, then the format is valid in whatever shape it comes,” he told 1 Granary, a biannual European art-school magazine and blog.

If you’ve seen Monocle magazine, you’ll perhaps get what Hack is talking about. Monocle was launched in 2007 by Tyler Brûlé (who created Wallpaper magazine in 1996 and sold it to Time Inc. in 1997 for a small fortune). I wrote for Monocle briefly in 2008, and at the time its London editor explained that the magazine’s target readership was cashed-up globetrotting young professionals. I didn’t really get it or them, and I fully expected Monocle to be gone within a year or two. But Brûlé had identified his community, and he knew how they saw the world. As the best magazine editors always can, Bail reminds me.

That Monocle didn’t fail is an understatement. It comes out in print ten times a year and around it Brûlé has built a twenty-four-hour radio station, a website, a special-issues publishing division, events and retail businesses and cafes. In 2018, Monocle is expanding into mixed-use residential developments in Bangkok. In November, Brûlé sold a 12.5 per cent stake in the business for US$6 million to Thai property developer Sansiri. The plan is to build houses that reflect the urban architectural designs that appear in the magazine. Monocle is much more than a magazine, and while I baulk at calling it a global brand, others don’t.

Like his contemporary Hack, Brûlé seems to be able to remake magazines at will. They move remarkably fast for middle-aged men, as someone has commented. But they’re not media barons in the way we’ve come to know them, and you sense they won’t be passing the baton on generation after generation, as the Bauers have done. That time is up. ●

Funding for this article from the Copyright Agency Limited’s Cultural Fund is gratefully acknowledged.