One day in July 2003 I found myself waiting for a bus in inland Ghana, somewhere between Cape Coast and Kumasi. It was the height of the rainy season, drenched in humidity, and we were stranded in a small village whose name I can’t remember. Our tro tro, as the Ghanaians call their privately run minibuses, had broken down and all its passengers, including the five goats on the roof, had been unloaded and told to wait.

Our group soon attracted the curiosity of the villagers, who took a break from their work in the surrounding fields to greet us and discuss our transport problem. A woman with a baby on her back brought plastic chairs and sat down with us to hear more about the country my friend Dani and I came from. All the while, her baby cried heartbreakingly.

The woman told us that she and the baby had been sick for a few days now. In an attempt to distract the child from its sorrows, I began to swing the colourful bracelet I was wearing. In no time the baby stopped crying and began to giggle. Its mother, visibly relieved, planted the child on my lap and said, “She likes you. You can take her with you.” Dani and I laughed at what we thought was a joke and so did the other women around us. But the baby, glowing hot from a fever, refused to go anywhere else and spent the next few hours on my lap, playing, sleeping and cuddling up to me.

When our tro tro was repaired and we got ready to say goodbye, I turned towards the mother to hand her baby back. But she refused to take the child. “You take her with you,” she said, “Take her to your country. You can be her mother and look after her.” Shocked at what seemed to be a serious proposal, I asked if she wouldn’t miss her daughter if she were sent off with a stranger. “Look,” she said, “my child is ill, she has a very high fever and I don’t have any medicine. There’s nothing here in this village, but where you come from she will have happiness and a good life. She wants to come with you.”

I left the village without the baby. Its heart-rending cry as I boarded the tro tro and waved goodbye has disturbed my dreams ever since, and I’m still baffled by the readiness of this woman to give away her only child to a stranger for a supposedly better life. Was life in the village really so miserable? Would there be no happiness in the baby’s future life? How was I to explain that in the part of the world where I came from people’s paths weren’t necessarily paved with happiness? And these thoughts led me to the underlying question: what, in the end, makes life worthwhile?

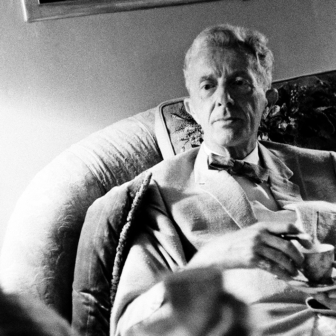

In this new book, Life Within Limits: Well-being in a World of Want, anthropologist Michael Jackson sets off on a journey to explore exactly this feeling of existential dissatisfaction, this deeply human belief that life should offer us more than what it currently does. Returning to visit the Kuranko people in the village of Firawa in Sierra Leone – the place where his first ethnographic fieldwork took him more than thirty years ago, and where later he lived for a time – he tries to understand what constitutes human wellbeing. Sierra Leone frequently appears in lists of the world’s “least liveable” countries and is usually represented as a place of poverty, hopelessness and conflict. Using ethnography as a tool to look deep into people’s everyday lives, Jackson shows that wellbeing is about more than financial or material stability.

Since Jackson first went to Sierra Leone, much has changed. On a political level, the country has been through a bloody civil war, traditional belief systems have been challenged, religious observance has changed and migration to other parts of the world has left its traces. The Kuranko people with whom Jackson has established long-lasting relationships have also changed – and so has the ethnographer himself. But he has stayed in touch with them through thick and thin, and it is the accounts of everyday life that he has collected along the way that make this poetically written book so gripping.

For an anthropologist, the technique of ethnography is, as Jackson puts it, “a way of thinking oneself through in the place of another.” During his thirty years of fieldwork the New Zealander, who is currently a visiting professor at Harvard University, has shown that the themes that preoccupy scholars can be communicated to a wider audience. His books engage readers by presenting the stories yielded by relationships he has built with people during his fieldwork, and it is through the way they see the world that broader existential questions are raised and illuminated. As a phenomenologist, he never imposes ideas or frameworks on people’s realities; instead, he focuses on “things as they are” and on the way they unfold in front of our eyes when we engage with others and their experiences. But his large body of work looking at “others” in order to reflect on “ourselves” is never simply a cultural critique of “the Western world.” In unfolding the struggles, heroic deeds, victories and losses of people’s everyday lives, he touches on the very basics of a shared humanity that he aims to look at in the light of its connections rather than its disparities.

At times, Life Within Limits reads almost like a travel essay. The anthropologist isn’t moving around in the way one would imagine the classic solitary researcher on a mission to observe how “others” define wellbeing. Instead, Jackson is accompanied by his seventeen-year-old son Joshua and his young Kuranko friend Sewa, who migrated to London some years ago. The company of the two young men, one making his first visit to Africa and the other visiting his home country, enriches the journey. Joshua’s experiences reconnect his father to his own early travels through the country; Sewa, whose story as a migrant in London featured in Jackson’s previous book, Excursions, allows the anthropologist to look at the topic of wellbeing through the “double lens” of someone who was born into Kuranko society and left it behind in the hope of a better life in Europe.

For Sewa, everything in his home country is different from how he remembers it. The characterisations of mutual regard, solidarity and friendship, which he had so often used in London to describe life in his childhood village, have disappeared. Jackson takes Sewa’s story as a starting point to think about the role of the past in our existential longing for something that goes beyond what life can offer us. This common human characteristic – the belief that the world was once a happier place but has fallen apart – shows that wellbeing, rather than being a simple and achievable goal, is a necessary fiction to keep us believing that there is something to live for. “Like the idea of utopia,” Jackson writes, “the idea of well-being captures a universal yearning to be more than we presently are and to have more than we presently possess.”

While material poverty plays an important role in the longing many young people feel for another, better place, it isn’t necessarily the decisive factor. In Firawa, social harmony has traditionally been of greater importance and – at least during Jackson’s first travels to Sierra Leone – poverty was accepted by people as being in the nature of things. But this view has changed radically. People now believe that poverty is the fault of those in power who have become wealthy at the expense of others. According to Jackson, this material scarcity translates into an existential feeling of being without, of being outside the same potentialities of other people’s lives.

It is with the story of ten-year-old Sira from Firawa that Jackson comes close to the heart of the complexities that surround human wellbeing. One evening, when he is sitting around the campfire with Sewa, a group of young girls approaches them to sing a few songs. The anthropologist is immediately fascinated by the poetic and thoughtful lyrics. Later he finds out that one of them, Sira, had composed all the songs. Jackson becomes interested in the girl’s story and visits her home. He is struck by the poverty. Sira and her mother live in a house that was burned down during the war and has only partly been repaired. Her mother’s only belongings are a mortar and pestle, a winnowing tray, a water pot and a fishing net. Sira used to be an excellent student, but she had to leave school after four years when her father left them and her mother could no longer afford the fees. As well as her talent for storytelling, the little girl also has the gift of divining. Twice a week she is visited by two djinns, she says, who show her how to collect medicinal plants from the bush and prepare herbal medicines to cure illnesses.

Although Sira doesn’t have enough to eat she complains not about a lack of food but about the lack of love, recognition and opportunity. This makes Jackson wonder what his own response to her plight should be. Would enabling her to go back to school help her or would raising her hopes for a better life simply complicate things further? Perhaps she has already worked out a way of coping within the limits of her situation through the stories she tells in her songs? As Jackson remarks, it is never possible to know a situation so fully that one can judge with certainty how to respond. “We act with good intentions, but the road to hell is paved with good intentions,” he writes. “We think we choose, but our situations also choose us.” But these thoughts don’t stop him from choosing to enable Sira to go back to school by paying her school fees.

For the Kuranko people the most important thing is to find the best way to bear the burdens of life. Drawing on this perspective, Jackson comes to the conclusion that wellbeing is not so much a reflection of hopes as a matter of learning how to live within limits. In Sira’s case, this means “making a virtue of her lot by singing on an empty belly.” Learning how to deal with the obstacles of everyday life entails more than the dream to escape or to be rescued. The difference between traditional and modern societies is first and foremost a difference between the limits humans have to struggle with. What really matters is that humans need to have a sense that they are not mere victims of whatever situation life throws them into. Rather, they need the feeling that their actions and thoughts make a difference.

The real value of Jackson’s books lies in the way he manages to hold a mirror to ourselves by examining the way others perceive the world. Ours is a time in which happiness is seen as a measurable state to which everyone is entitled. Countries like Sierra Leone not only appear at the very bottom of international rankings of “happiness” or “quality of life” but have come to represent places where life is almost “unliveable.” By dismissing suffering, pain and effort – those necessary counterparts of happiness – we risk losing the tools to deal with constraints; any deviation from monotonous happiness is perceived as a major disruption.

Anthropologist Arthur Kleinman once met a seventy-eight-year-old American artist who suffered from leukaemia. Tired by the attempts of people around him to make him hope for a happy ending, he asked, “Do I have to go with a smile on my face? That seems to me ridiculous, and insulting.” I think this man’s question helps to explain why the Ghanaian woman’s drastic call for my help was so disturbing. I was about to return to a highly individualised world in which people are led to believe that anything is possible and there are no borders or limitations – a view of life drastically out of step not only with life in that village, but also with human life in general. As Hannah Arendt writes in The Human Condition, pain and effort are not simply symptoms that can readily be removed from our lives; they are modes in which life makes itself felt. Referring to Greek mythology, she concludes that the “easy life of the gods” would be a lifeless existence for humans. What marks us as genuinely human is exactly our ability to move amid the limits of the world we are born into.

That knowledge won’t stop me from hoping things have changed for the better for the girl and her mother. Nor will it stop me from thinking that limitations are distributed unfairly. We mustn’t demand that the poor and desperate simply accept these constraints. The people whose stories we hear in Jackson’s book show that, despite everything, humans never cease to push the boundaries and will go on hoping for the easy life of the gods. •