“Real estate agents across the nation have declared war on Bill Shorten’s negative gearing overhaul,” the Australian reported last Friday. If that doesn’t strike you as surprising, perhaps the second half of the sentence will. According to the paper, the agents will run a four-week campaign “using customer databases to target buyers, sellers, landholders and tenants in key marginal seats.”

No doubt the agents will argue that they are merely providing their customers with important market information. But when companies start using their extensive holdings of private data to serve their own interests during an election campaign, we should take notice. Who needs Cambridge Analytica when an industry’s own databases can be weaponised in this way?

Admittedly, there are precedents. In the 1940s, for instance, banks campaigning against the Chifley Labor government’s nationalisation plans used their employees in marginal seat campaigns, lobbied customers by mail and encouraged tellers to pass information across the counter to voters using their services. This time, though, sophisticated data-management capabilities can be used to target information to specific seats and even individuals.

The real estate agents aren’t alone. Master Builders Australia reportedly plans to campaign against Labor’s negative gearing and capital gains tax policies in those marginal seats that are home to significant numbers of construction workers. (It isn’t clear how targeting building workers in this way will gel with its campaign for Labor to retain the Australian Building and Construction Commission.) Master Builders no doubt hopes it can mirror the success of the Housing Industry Association, which claimed that its campaigns in the early 1990s forced the Hawke–Keating government to reverse its abolition of negative gearing. (The HIA, too, had campaigned to reduce union power in the building industry).

These campaigns by real estate agencies and building companies don’t simply reflect pressures within the banking or property industries; they also have a deeper economic significance. They reflect the difficulty Labor faces in attempting to raise extra tax revenue to reduce debt and put extra funds into health, education and other government services.

A key example is the estimated $22 million campaign by mining companies against the Rudd government’s mining super profits tax, which contributed to Kevin Rudd’s replacement as prime minister by Julia Gillard. Spooked by the mining industry’s campaign, Labor made hasty concessions that massively reduced the projected revenue. As a consequence, it missed out on an opportunity to use the wealth generated during the mining boom to help repair government finances after the global financial crisis. Such a windfall would have helped compensate for the substantial falls in government revenue that were making it so much harder for Labor to return the budget to surplus.

More centrally, business campaigns against Labor play into the key election issue of who can be trusted to manage the economy. Business opposition to Labor can not only scare voters about specific policies, it can also scare voters more generally by suggesting that Labor won’t be able to run the economy effectively. After all, many ordinary voters’ jobs and incomes depend on investment in the private sector, and these campaigns suggest that Labor is ill-equipped to manage an economy in which businesses play a crucial role. Opposition from business can therefore have a very significant impact on voters’ decisions.

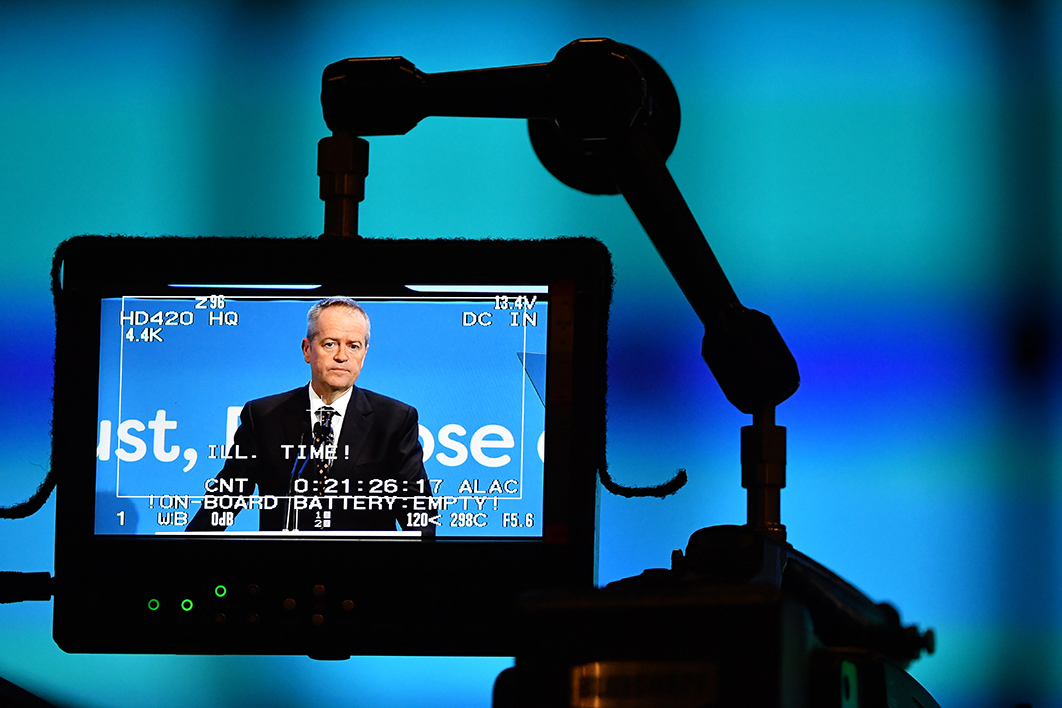

Labor seems to be more aware of the risks involved in being perceived as anti-business than it was during the 2016 election campaign. Indeed, Bill Shorten has been making significant efforts to reassure and court business leaders. He has also toned down his rhetoric, though he is still arguing that the Liberals look after the “big end of town” while Labor is trying to make the economy work for everyone but especially the working and middle classes. In particular, Labor is placing more emphasis on its argument that improving wage outcomes will also benefit business. As Shorten said in his budget reply speech, “We need to get wages growth going again — for workers, for the economy, for confidence and consumption. Because when we boost the spending power of working people, that money flows back into the tills of small businesses.”

Labor may also believe that its previously stronger rhetoric is no longer necessary given how the banking royal commission has contributed to negative attitudes towards at least some sections of big business. After all, even Scott Morrison conceded that the Liberals would not be taking their tax cuts for big business to the electorate this time round because business needed to do more to earn the public’s trust and build support for change.

At a time when even the Reserve Bank governor is advocating wage increases in order to lift consumption and trust in the economy, Labor’s position is not radical. As I argue in a new book, it reflects Labor’s attempt to develop a social democratic strategy for current economic conditions and it indicates a partial shift away from the neoliberal policies of the Hawke and Keating years, including in industrial relations policy. It is a shift that risks provoking business opposition, however, and not just because of Labor’s tax policies. Sectors such as the restaurant and cafe industry, for example, are strongly opposed to increases in the minimum wage. After all, businesses may be happy for other employers’ workers to have higher wages to spend but not want to pay their own employees more.

The Coalition is not having it all its own way in terms of business opposition. The government’s attempted scare campaign over Labor’s electric vehicles policy received a negative response from Toyota and Hyundai, given the automotive giants’ own plans to increase electric car production. Indeed, many sectors of business may be well ahead of the Coalition when it comes to climate change and energy policy.

Despite being ahead in the polls, Labor still has reason to be concerned about these campaigns. After all, businesses helped defeat the Chifley and Whitlam governments and have played a role in preventing Labor gaining office. Business opposition was only one of many factors contributing to Labor’s defeats, of course, but it was a significant factor nonetheless, and one that commentators need to watch during the 2019 campaign. •