Matching expectations, last month’s federal budget received a more positive response than last year’s. But perhaps, as Ross Gittins points out, this is simply because the cuts are less obvious than they were in 2014 and are targeted at groups regarded as “less deserving.” ACOSS argues that this year’s budget still fails the “fairness test,” pointing out that it retains severe cuts to payments and programs from last year and in some cases links new spending measures to those stalled savings measures.

Modelling for the Labor Party by the National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling, or NATSEM, found low-income families could lose up to $3700 per year in 2015–16, and an increasing amount in subsequent years, under new measures in the budget and cuts still pending from last year. Using its “microsimulation” model, which both the Howard and Rudd–Gillard governments used as a policy tool, NATSEM estimated that by 2018–19 the lowest “quintile” (or 20 per cent) of couples would be 7 per cent worse off and the lowest quintile of lone parents would be 8 per cent worse off.

Within quintiles of couples with children, reports NATSEM, only 11 per cent of the poorest quintile and 22 per cent of the second-poorest quintile would be better off. Yet a little over 90 per cent of the richest quintile would gain from the package. Couples without children would be less well off to a smaller degree, while most single person households would be slightly better off.

The government counter-argues that the NATSEM calculations don’t include any “second-round” effects of the budget changes. Asked about NATSEM’s modelling during question time, the prime minister said that this omission meant it was “a fraudulent misrepresentation” of the budget. Returning people to work, he said, was “the whole point of the policy measures.”

But the government hasn’t released any of its own modelling of the budget’s impacts. Last year it also chose not to include tables showing the impact of the budget on different family types, despite the fact that these tables have appeared in all budget papers since 2005. Our attempt last year to reproduce that table showed why: the budget burden fell most heavily on low-income households.

This year the household table has returned. But rather than show the impact of budget changes, it reports how many single full-time average wage earners it takes to raise the tax revenue required to fund the benefits paid to other household types, particularly families with children and age pensioners. So, for example, a “welfare rich” sole parent with two children under six who earns $30,000 a year is said to have a higher disposable income than a single person earning $80,000 a year. The final column of the table shows that it takes 1.9 average workers to pay for the benefits received by the low-paid lone parent.

This variation on the “lifters” and “leaners” theme is at odds with what we know about the “piggy bank” function of the welfare system. Over the period 2001–09 nearly two-thirds of working-age Australian households included somebody who received an income support payment – and this does not include people receiving family payments or age pensions. There’s no mystery about the reason: over time, the majority of Australian households experience periods of unemployment, illness or disability, or family break-up. As the latest ABS Labour Force Experience Survey shows, during 2011, when the average number of people unemployed was around 600,000, nearly 1.7 million people – or 10 per cent of the adult population – had at least one spell of unemployment.

Put another way, the individuals implicitly labelled “lifters” in the budget table might have appeared in a different column last year, if they had needed welfare support, or might appear there next year, courtesy of Australia’s flexible labour market and the life risks that everyone faces.

As Eva Cox and Greg Jericho have pointed out, the table also adds childcare payments to disposable income without deducting the cost of childcare. On the basis of that misleading presentatation of the figures, the Daily Telegraph asserted, under the headline “Joe Blasts ‘Welfare Rich,’” that these families “have more money to spend than workers” but didn’t acknowledge that after childcare costs are deducted these families have less money to spend than workers without children (and are also workers themselves).

It’s important to remember that families only receive childcare assistance because they have already paid childcare fees, and they can still have large out-of-pocket expenses. One of the aims of the government’s childcare package is to reduce those expenses. Its decision to include childcare benefits in the calculation of disposable income is all the more surprising given that the new arrangements would see this assistance paid directly to childcare centres.

New spending versus last year’s savings

For families with children, the package of childcare reforms, expected to cost $4.4 billion over four years, is the budget’s centrepiece. Looked at purely in money terms, the proposed changes appear progressive: they increase assistance for low- and middle-income families more than for high-income families. As family incomes rise, the subsidy for childcare costs reduces from 85 to 50 per cent. But parents will have to work at least eight hours a fortnight to qualify for up to thirty-six hours of childcare subsidy every two weeks, and they will have to work at least forty-nine hours over the same period to get the full hundred hours per fortnight subsidy. These changes will have distributional effects that are not easy to capture in money values.

The government proposes to finance the package by pushing ahead with some of the 2014 budget measures still blocked in the Senate. These include the plan to freeze the rates of family tax benefit, or FTB, for two years, reduce the value of FTB supplements, and freeze eligibility thresholds so that more people lose payments as their income increases. A fourth measure would see families no longer receive FTB Part B when their youngest child turns six. At present, FTB-B is paid to eligible households until the child leaves high school. According to the Parliamentary Budget Office, these 2014 budget initiatives would save around $9.4 billion between 2015–16 and 2018–19.

The government also expects to recoup spending over the forward estimates through a number of initiatives targeting family payments. Savings of $177 million are expected to flow from the complete abolition of the large-family supplement, $500 million from ceasing payments to families that refuse to immunise their children, and $967 million from ending paid parental leave “double dipping” (a characterisation that has been strongly criticised).

Last year’s unpassed savings and the new savings proposal add up to much more than the cost of the proposed childcare package. In other words, the total volume of assistance for families is decreasing, which means either more losers than winners, or that the losers on average will go backwards by more than the winners gain.

To assess the overall impact of the budget on households, then, we need to look in more detail at who wins from the childcare assistance proposals and who loses from last year’s cuts and the new savings proposals.

Winners and losers

Who wins? The Department of Social Services, or DSS, reports that in 2013 around 930,000 families with 1.4 million children benefited from childcare assistance. These families will be the main winners from the government’s childcare reforms – together with those who enter the workforce as a result of second-round effects. It should also be noted that among the families that do benefit, not all will move off welfare. In many instances the father will already have a job, and the mother will move into paid employment or will increase hours of paid work.

Who loses? Many families receiving childcare assistance also receive FTB Part A. For these families, any gains from childcare reforms will be reduced by FTB-A changes. They may still come out as “winners” overall, but their gains will be lower. The DSS data also reveal that in 2013 there were 570,000 families with close to 1.1 million children receiving the maximum rate of FTB-A, and these will be the largest proportionate losers from the proposed freezing of FTB-A for two years. A further 328,000 families with incomes above the first threshold face the double effect of a freeze on rates and on thresholds.

There are also 722,000 families receiving FTB-B whose youngest child is aged five years or over, most of whom would lose from the lowering of the eligibility age for FTB-B. According to the Parliamentary Library’s analysis of the 2014 budget, around 85,000 single parents with children aged six and over who receive Newstart Allowance will find their benefits cut by up to $2,300 per year. The subset of these who successfully move into paid work may be overall winners. But it seems clear that the number of losers will be much larger than the number of winners, which is what we would expect when the savings are significantly more than the new spending.

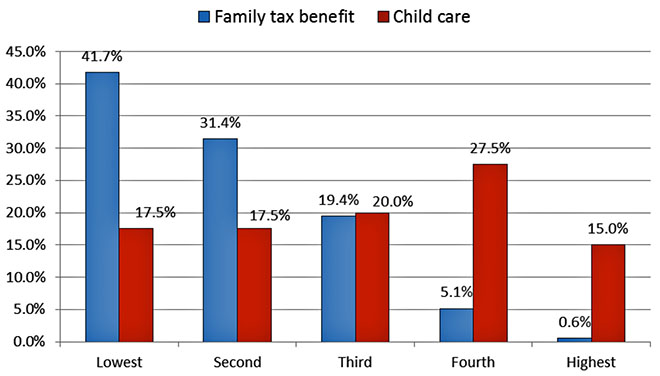

Figure 1: Distribution of spending on family tax benefits and childcare assistance by quintiles of equivalised disposable income, Australia, 2009–10

Share (per cent) of spending received by income quintile

Source: Calculated from Table 5, datacubes, ABS, Government Benefits, Taxes and Household Income, Australia, 2009–10.

It is no surprise that the government’s childcare reforms will favour middle- and higher-income families over lower-income families. Most families receiving childcare assistance have higher average incomes than the lone parent families or single earner couples who will be the biggest losers from the cuts to family payments. For example, the ABS Income Distribution Survey for 2009–10 reports that the poorest 40 per cent of households receive around 73 per cent of FTB funds but only 35 per cent of childcare assistance. Correspondingly, the richest 40 per cent of households receive around 40 per cent of current childcare spending but only 6 per cent of family tax benefits.

The fact that the published DSS and ABS data suggest that the government’s overall package is regressive, but can’t definitively establish it, is precisely why NATSEM’s microsimulation modelling is so valuable. By applying the policy changes to around 45,000 real families from two years of the ABS Survey of Income and Housing, the model provides a more comprehensive analysis of the overall impact of budget changes.

Second-round effects: will they make a difference?

As noted earlier, the government has emphasised that NATSEM’s calculations don’t include any second-round effects of the budget changes, and that returning people to work was “the whole point of the policy measures.” In essence, they are arguing that the policy package makes work more attractive both by reducing the cost of childcare and by cutting benefits to families.

On one level this sounds reasonable. But, as Ross Gittins has pointed out, the government doesn’t appear to have taken behavioural changes into account in estimating the savings flowing from its “no jab, no pay” policy. And treasurer Joe Hockey has conceded that “as a rule” – in any federal budget, that is – “second-round effects are not taken into account.” This is largely because the size of any behavioural response is unclear, regardless of the likelihood that there will be one. A 2007 Treasury working paper points out that estimates of how many people will move back into the labour force as a result of tax and benefit changes can vary widely, while the Productivity Commission opts for a range of estimates of the effect of increases in childcare costs on hours of work.

In its report on childcare, which fed into the government’s package, the Productivity Commission was cautious about the impact of its recommendations on the labour market. It estimated that the supply of potential employees might increase by roughly 165,000 on a full-time equivalent basis if childcare shortages and affordability could be dealt with. But it also estimated that increases in workforce participation would be “small” – that its recommended approach would increase the number of working mothers (primarily in low- and middle-income families) by 1.2 per cent (an additional 16,400 mothers), about 10 per cent of the total potential gains if childcare affordability and accessibility were no barrier at all.

The Guardian reported that the government had calculated 240,000 families could increase the hours they worked because of the proposed changes to childcare assistance. This figure – derived from an online survey said to be representative of the population – seems similar to the Productivity Commission’s estimate of the total potential gains given no barriers to childcare, although this is not entirely clear. Clearly, there is a very large difference between 16,400 and 240,000.

It is worth emphasising that this estimate appears to combine the effect of increased hours among families already in paid work and the effect of people moving into work for the first time. In terms of offsetting the regressive impact of changes to family payments, it is the impact of people moving from welfare into work that is most relevant. Increases in hours of work among those who already participate in the labour market will help offset any loss of family tax benefits, but will tend not to be as progressive as moving families from welfare to work.

It is also worth mentioning that the budget’s economic parameters suggest that the impact on employment is not likely to be substantial. Although the labour force participation rate is projected to rise marginally from 64.6 to around 64.75 per cent over the forward estimates, the unemployment rate is projected to increase from 5.9 per cent to between 6.25 and 6.5 per cent, which implies a small fall in the proportion of the adult population who are employed.

Other effects of the overall package also need to be considered. Deborah Brennan and Elizabeth Adamson of the Social Policy Research Centre at the University of NSW conclude that the new scheme will benefit low- and middle-income families who have secure, predictable employment and use services that charge the benchmark fee (or lower). It will disadvantage Indigenous children, they say, as well as children in the poorest families and children whose parents have casual work, variable hours or insecure jobs. This reflects the increase in the number of hours that must be worked in order to receive the maximum subsidy. Other criticisms of the childcare package focus on the fact that it neglects care for the most disadvantaged children and plays down the important child-development aspects of early childhood education.

Our colleague in the Crawford School, Bob Breunig, agrees that “positive labour supply effects should ensue from tilting subsidies towards those who are less well off,” but goes on to point out that failing to index benchmark childcare fees, or indexing them only to a broad measure of inflation, could result in substantial real decreases in support to families over time.

Towards a social investment strategy?

It is possible to present other arguments in favour of the government’s approach to shifting spending towards childcare and away from cash benefits to families.

For some time the European Commission has been interested in a social investment strategy, which is defined by the Policy Network as “the set of policy measures and instruments that promote investments in human capital and enhancement of people’s capacity to participate in social and economic life as well as in the labour market.” Shifting social spending away from “passive” social policies such as family tax benefits towards “active” spending such as childcare and active labour market programs could be seen as a means of ensuring the sustainability of social programs and promoting economic growth.

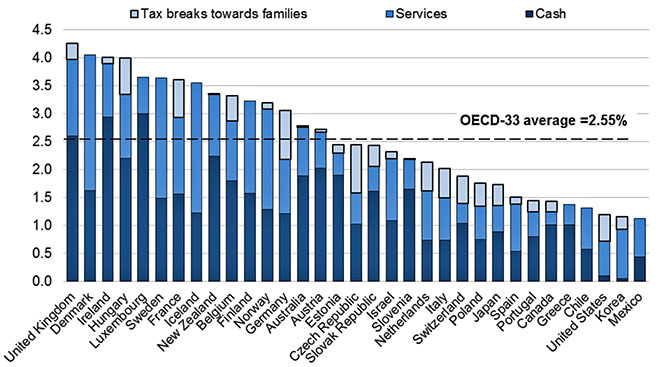

What is the balance between “active” and “passive” spending on families in Australia? Figure 2 shows that public spending on families in 2011 was the fourteenth-highest in the OECD, at 2.79 per cent of GDP, just above the OECD average of 2.55 per cent of GDP. Spending on cash benefits, at 1.89 per cent of GDP, was the eighth highest, but Australia ranked sixteenth for spending on services, at 0.86 per cent of GDP, below the OECD average of 0.99 per cent. The Nordic countries, where the social investment approach is regarded as most developed, spend two to three times as much as Australia as a percentage of GDP on services for families. Around a third of children under three years are enrolled in formal childcare services in Australia – just above the OECD average – but enrolment is over 50 per cent in Norway, Iceland and the Netherlands and approaches two-thirds in Denmark.

Figure 2: Public spending on family benefits in cash, services and tax measures, OECD countries, per cent of GDP, 2011

Source: OECD, 2015, Family database.

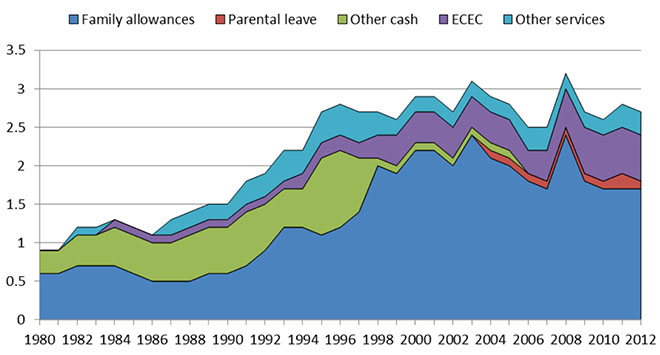

Figure 3 shows trends in family assistance expenditure in Australia from 1980 to 2012. Spending grew from 0.9 per cent of GDP in 1980 to 2.7 per cent of GDP in 2012, initially peaking at 3.1 per cent of GDP in 2003 and peaking again at 3.2 per cent of GDP at the time of the stimulus package in 2008.

Figure 3: Public spending on family assistance, Australia, per cent of GDP, 1980 to 2012

Source: OECD, 2015, Social Expenditure database. ECEC refers to early childhood education and care.

Over the long run, the rise in spending is mainly accounted for by increased spending on family allowances (FTB Parts A and B). Most of this increase occurred in the late 1980s and the first half of the 1990s following the Hawke government’s child poverty pledge, rather than as a result of the assumed increase in “middle-class welfare” during the Howard government. Since the mid 1990s, the increase has largely reflected higher spending on early childhood education and care, which grew from 0.2 to 0.6 per cent of GDP and from less than 10 per cent of total family spending to over 20 per cent.

In this sense, Australia has already started on a shift from cash benefits to spending on childcare services, a shift partly explained by the increase in female labour force participation during the period.

While there is an extensive body of literature arguing for the social investment approach, it is not without its critics. Chiara Saraceno has argued that the “ideal adult worker model” that underlies this approach

hides, and to some degree even takes for granted, gender inequalities in both the household and the labour market. [It] also undervalues the subjective and relational meaning of caring within households, while attributing to families a mainly functional role regarding societies and labour markets.

In addition, the Policy Network has highlighted possible tensions between the principles of social investment and social protection. Doubts have also been raised about whether this approach has the capacity to support those most at risk of poverty or social exclusion, a point particularly relevant to the government’s proposed shift from cash benefits favouring the poorest households to childcare support favouring those already in the labour market.

While the government’s childcare package, in combination with cuts in family payments, could be defended as a shift towards a social investment approach, it would be a stretch in current circumstances to see it as such. Neither the government nor the opposition has articulated a clear vision for moving towards this goal. Australia is a long way from the levels of social investment in childcare and labour market support that are characteristic of such a strategy. The fact that the expenditure savings from the proposed changes in assistance for families are more than double the extra outlays for childcare suggests that this package is motivated more by budgetary than social outcomes.

Calculating who wins and who loses from the budget, or from other policy changes, is an essential component of sensible analysis of public policies. It is normal practice of governments throughout the world to identify winners and losers from this kind of change. Since its 2010 Spending Review, for instance, the UK Treasury has published analyses of the impact of the budget on households, with the most recent analysis being for 2015.

Governments should welcome the type of evidence-based policy analysis exemplified by NATSEM’s analysis, and ideally provide it themselves. In a period where politicians complain about the poor quality of the conversation, analysis like this focuses the debate on how real people will be affected. •