When the Howard government lost office in November 2007, former treasurer and heir apparent Peter Costello displayed rare political farsightedness when he declined to throw his hat into the leadership ring.

It was a wise move. A honeymooning new prime minister and government would have buried him, as they did Brendan Nelson and then Malcolm Turnbull. Instead of remembering him as the country’s longest-serving treasurer and the man who (some believe) might, just might, have rescued the Coalition government had John Howard not been so stubborn, our final image of Peter would have been that old staple: the hapless opposition leader, unable to land a blow, who is eventually, humiliatingly, put out of his misery.

And yet, over the next two years on the backbench, when it was widely believed he could still have the leadership with the snap of his fingers, Costello regularly flirted with the party room, giving the impression he might perhaps be interested — Watch me perform; don’t you miss me? — but never quite got around to popping the question. It was as if he just loved being talked about.

Costello left parliament in December 2009, days after Tony Abbott replaced Turnbull as leader. An election was due the following year, one that didn’t look competitive for the Coalition but ended up a line-ball.

It’s easy to imagine Costello kicking himself several times about that decision. He hasn’t seemed a happy chappy since then. Like many of our former senior politicians, he’s a bit underutilised.

On budget eve he paid a visit to ABC’s 7.30 to remind us of his existence. There he was, bobbing and weaving, chewing the scenery, fluttering his eyelids, boasting of his record, complaining about income-tax rates on high earners, chastising the incumbents for not being as wonderful as him.

He even gave a straight-faced imprimatur to Scott Morrison’s loopy self-imposed tax limit of 23.9 per cent of gross domestic product, despite himself exceeding that level on five occasions when he was treasurer.

Does this performance, aimed squarely at the Liberal establishment, indicate a lust to return to politics or is it just more attention-seeking? Probably the latter; the former treasurer would be realistic enough to know that today’s economic circumstances, plus those swollen Senate crossbenches, would easily prove the better of him.

The years from the mid 1990s to 2007 — as governments at state and territory level, here and overseas, can attest — were a dream time to be in office. Wallets were open and coffers overflowing. The world is different since the global financial crisis, and Morrison could only dream (and only in the forward estimates) of reaping anything approaching 23.9 per cent of GDP in tax.

Which brings us to Canberra, awash with journalists, lobbyists and hangers-on, where it’s budget week.

Unless the government moves next year’s forward a month, or Malcolm Turnbull courageously follows Peter van Onselen’s advice in the Australian and decouples the Senate and House of Representatives elections, this one is a pre-election budget. The role of such budgets, according to conventional wisdom, is to buy enough votes to help lock in an election win. But here’s a little secret: political strategists don’t really know what determines election outcomes. It’s all rather hit and miss. They have their bags of tricks, which they dare not neglect just in case, and budget giveaways are one of them.

More important for political survival is a government’s perceived economic competence. As a factor, it’s not what it was before the bottom fell out of the global economy, but it still matters.

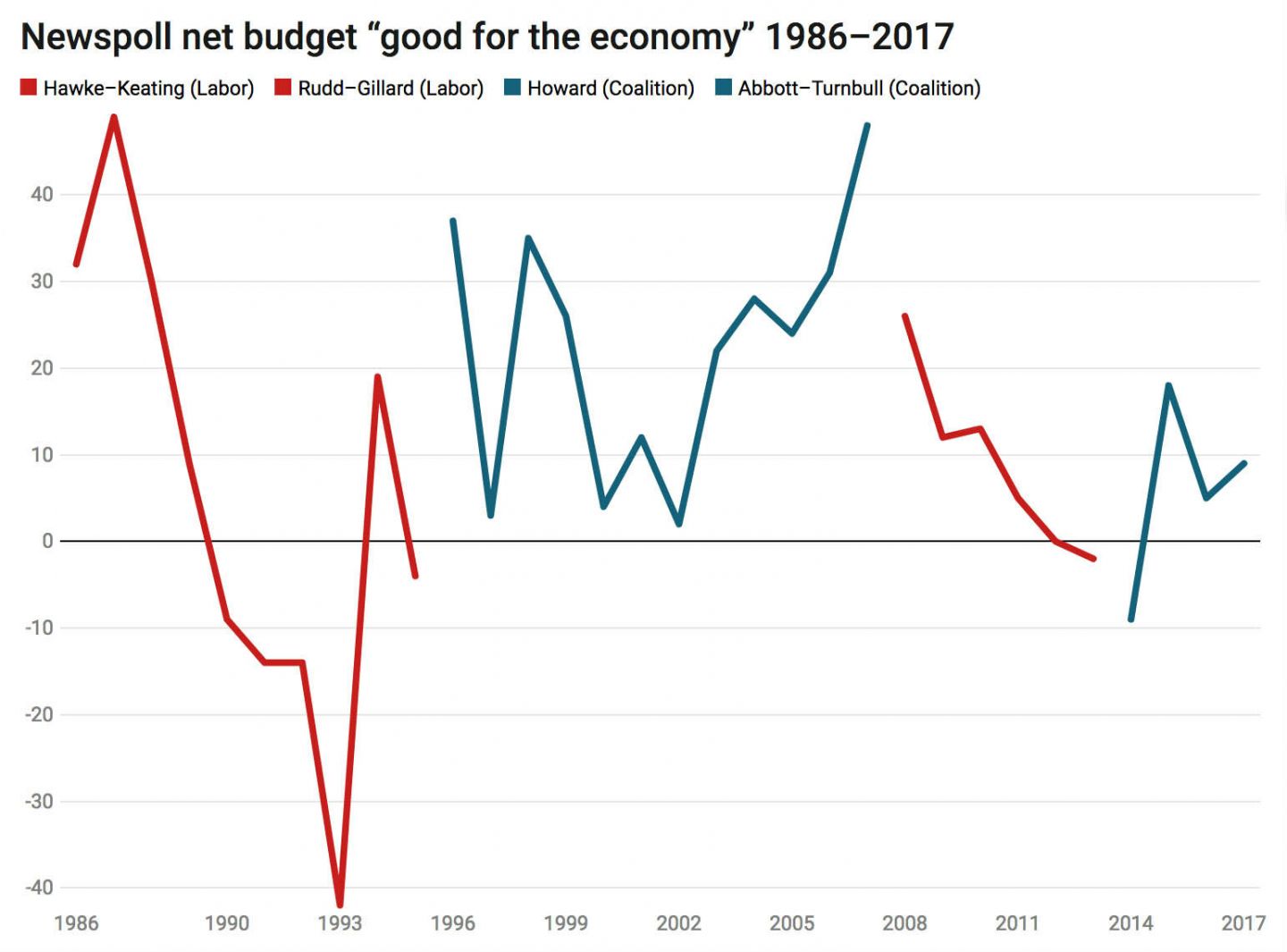

Since Newspoll began in late 1985 it has put a series of questions about each year’s budget, and probably (in my opinion, that is) the most important, the one that gets to perceptions of economic capability, is this:

Thinking of the federal budget handed down by the treasurer, [insert name], recently. Overall do you believe the budget will be good or bad for the Australian economy? If good do you believe it will be extremely good or just quite good? If bad do you believe it will be extremely bad or only quite bad?

Subtracting “bads” from “goods” gives a net “good for the economy” rating for each budget. They look like this on a graph:

Chart: Peter Brent, insidestory.org.au ● Source: Newspoll ● Created with Datawrapper

It’s a rollercoaster ride — and boy oh boy did the re-elected Keating government’s effort in 1993, with its hikes on indirect taxes and “withholding” of half the “L-A-W” tax cuts, fail to impress.

The second-best-received budget in Newspoll history (by this measure) was Costello’s last, in 2007. It sent the betting markets back to the Coalition for a little while, but didn’t do much for opinion-poll voting intentions.

As the graph shows, “budget bounces” are mostly observed in the breach, and anyway a “bounce” is almost by definition something short-lived and unsustainable.

Costello’s well-received 2007 budget didn’t prevent a change of government six months later. But that doesn’t mean it (or more accurately, its part in making voters believe they were blessed with a government of splendid economic managers) didn’t limit the size of the loss. To the very end, Australians believed in Howard’s and Costello’s economic prowess; in hindsight, after the bottom fell out of the world economy the following year, they looked even better.

Losing office before the economic cataclysm turned out to be wonderful for their legacy. The two key figures from 1996–2007, Howard and Costello, dine out on those memories to this day. And their reputation even helped Tony Abbott get elected. ●