Earlier this week media people gathered for the launch of a book of journalists’ stories. Nothing remarkable about that, you might say. But these aren’t the stories journalists write about other people; they are journalists’ accounts of their own lives and careers, and the tidal wave that has engulfed what is surely the fastest-changing profession on the planet.

Many of the stories come from the “golden age” of Australian journalism, bathed in the sweet light of nostalgia but also revealing a dark side. Others describe what happened when the golden age ended with the collapse of the business model that supported most journalism.

Although the collapse is seared into journalists’ consciousnesses, it isn’t well understood in the community. Recent research by the News and Media Research Centre at the University of Canberra found that two-thirds of Australians aren’t aware that commercial news organisations are less profitable than they were ten years ago. And yet this is the story that underlies almost every failure of today’s journalism.

The book being launched was Upheaval, edited by journalism academics Andrew Dodd and Matthew Ricketson, which draws on interviews with fifty-seven journalists conducted in partnership with the National Library’s oral history program. Rich with anecdote and personal perspectives, it includes vivid accounts of the traumatic loss of a vocation.

There are prominent names here. Amanda Meade tells us about working for the Australian, and how she got into trouble for being seen speaking to the ABC’s Kerry O’Brien at a time when the Murdoch paper was attacking the public broadcaster. George Megalogenis confides his thoughts when he put his hand up for redundancy at what he correctly deduced was a tipping point for the industry — in 2012, when both Fairfax and News Corporation shed up to a fifth of their editorial staff. David Marr details the twists and turns of his career. Cartoonist John Spooner recalls realising that he was considered more disposable than the Age’s other flagship cartoonists, Michael Leunig and Ron Tandberg.

All of this raises a question. Were things better “back then” — by which I mean in the 1970s, 80s and early 90s, when newspapers earned rivers of gold from classified advertising, families gathered around a single screen to watch the evening news, and newsrooms were awash with resources and largely unquestioned power.

I am as prone to nostalgia as anyone. I started my career as a cadet at the Age in 1982. (Matthew Ricketson was part of the same intake.) In the years that followed, I succeeded in grumbling my way through and out the other side of what I now know was the golden age.

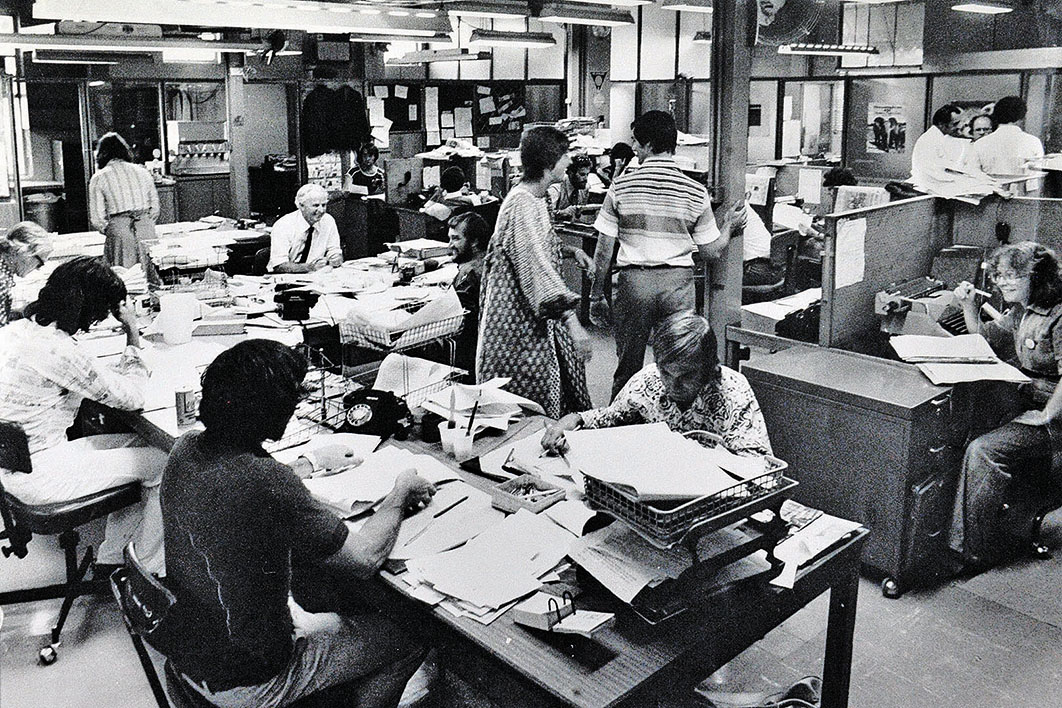

I remember newsrooms that, as Upheaval puts it, smelt “of stale sweat from the adrenaline and anxiety that drive daily journalism; of beer-soaked, never-quite-cleaned carpets and… cigarette smoke.” I remember the extraordinary resources we had: drivers to take us to stories; many, many subeditors to check our work; an army of “readers” who were employed to spot the mistakes that had still been missed.

As Marr recalls, newsrooms were unusual workplaces, “crazy universities” full of experts on the strangest of things. Newspaper men — and they were mostly men — were a breed apart. They were not the polished, tertiary-educated journalists who now dominate the newsrooms. They had a hard, twinkly-eyed charm, a knockabout empathy, a quick wit, and an intelligence that, if they had belonged to a different generation, would have sent them to university.

They dominated not only numerically but also because of their liveliness of mind. They were not in any sense intellectual — in fact, they were largely anti-intellectual. But they could grab a telephone and file a story in no time at all. They marshalled their thoughts quickly, put them forcefully and moved on. They were arrogant, of course. But that arrogance was masked by the real power that came with having access to the means of publication and broadcast.

Upheaval also documents some of the dark side. Jo Chandler talks about concealing her pregnancy at the Age in the knowledge that it could rob her of an expected promotion. Michelle Grattan recalls being denied the trades hall round because she might be exposed to “bad language.” Worse than this are the accounts of sexual harassment and assault, of women who could not bend down in the office without attracting offensive comments. Quite literally, it was hard for women to move, or even to exist, in these workplaces.

What brought this world to an end? It’s a complex story, but the dominant theme is the collapse of the business model, brought about by the internet.

The destruction came in two waves. First, the classifieds disappeared to dedicated online sites that better enabled people to search for jobs, cars and homes. At the same time came the beginning of the end of “appointment television,” with people able to view whenever they wished.

The industry was still struggling with that disruption when the second wave hit, starting around 2007. This was the rise of Google, Facebook and other social media platforms. They quickly grabbed most of the remaining advertising revenue.

Reliable estimates of job losses are hard to get. The Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance estimates that 5000 journalists’ jobs have been lost over the last ten years. Data provided to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission by the main media companies show that the number of journalists in traditional print media businesses (including their websites) fell by 20 per cent between 2014 and 2018, at a time when Australia’s population and economy were growing strongly.

The easy conclusion, of course, is that things must have been better “back then.” More outlets, particularly local newspapers. More reporting of local courts, councils and public figures. More interstate and overseas correspondents. More specialist journalists with depth of expertise. In Canberra, more and deeper engagement with thinking at the highest levels of the public service.

But not everything is worse. In the golden age, newsrooms were overwhelmingly run by white men, and nobody saw that as a problem. We told ourselves that it was our job to reflect the community we served, but we were almost completely blind to the absurdity of that claim when women were sidelined and people of colour almost completely absent from the newsroom. Things are a bit better now, with a long way still to go.

The mainstream media has undoubtedly lost power, and with it some of its arrogance. Even the Murdoch press can no longer turn an election through sheer vote-swaying heft. Instead, it attempts to fix the parameters of public debate — though even that power is under challenge.

The ranks of professional journalists might have thinned, but many more people are actively engaged in the newsmaking process. Consider, for example, how data analysts, putting their work out on Twitter, have contributed to our understanding of the pandemic.

The professional media attempts to maintain its position at the centre by corralling the work of others, largely in the format of the “live blog” — a kind of aggregation of things that are happening “out there,” including on social media. There is plenty to celebrate in the rise of social media platforms: voices once excluded from public debate can now be heard. And there is also plenty to fear, for the same reason.

Above all, the thinning of journalistic ranks affects just about everything about the media. Surely one of the reasons the pandemic has been politicised is because it is being reported by political journalists. The specialists of old — the medical reporters, the science reporters — are largely gone. And the disruption is not over.

Plenty of experimentation with business models has taken place. For serious media, clickbait didn’t work. Now the name of the game is persuading people to pay to access news online.

What will people pay for? We are still finding out, but there are encouraging signs that good journalism is the answer. The world’s serious newspapers now earn more than half their revenue from subscriptions.

Countering that optimism, the University of Canberra’s research tells us that only 13 per cent of Australians are paying for online news, which is below the global average of 17 per cent. The vast majority of those who are currently not paying say it is unlikely that they will pay in the future.

I don’t think I am only being nostalgic when I say that it is more important than ever for society to pay attention to and care about its journalistic capacity, which these days is more an ecosystem than a monoculture. •