Treasurer Jim Chalmers tells us the budget is back in surplus for the first time in fifteen years. He’s the third treasurer who’s told us that, and this is the fourth budget for which the claim has been made. But this is probably the first “surplus” we can believe in.

Chalmers’s former boss, Wayne Swan, forecast a $21.7 billion surplus in the 2008–09 budget. The global financial crisis took care of that. Four years later, heedless, Swan forecast an implausible $1.5 billion surplus. He was only $20 billion out. And we remember the hubris of Josh Frydenberg and Scott Morrison at the time of the 2019–20 budget, with their coffee cups printed “Back in Black.” Their budget was already heading for red when Covid arrived and gave them a good excuse.

This time, it’s the current financial year that Chalmers says will end in surplus. We’re in May now, and the year ends on 30 June. It would be a bad shot if he missed from this close. Let’s assume the long wait is over: Australia’s federal budget is finally back in surplus, even if only by $4 billion or so.

But will it last? The Murdoch hunting pack has focused on the budget’s forecast that this will be a one-off, and next year the budget will be back in a deficit that will then grow bigger still. And yes, that is what the budget forecasts say. But when you read the assumptions underlying those numbers you realise they’re not really forecasts, but rather a worst-case scenario. They assume a collapse of global commodity prices.

Why does Treasury give us a worst-case scenario? Because we don’t like unpleasant surprises. If a tradie promises to do the job for $1000 but then lifts his bill to $2000, we get cross. But if he promises to do it for $2000, but then after doing it, says “No, that was easier than I expected, $1000 will do,” we think he’s a great bloke.

Treasury now works on the same principle. It begins by forecasting a worst-case scenario: in this case, adopting the lowest market forecasts for prices of iron ore, gas and coal. The bears always predict a price collapse; that would flatten the profits of Australian miners, and hence Australia’s company tax revenue.

On that basis, Treasury forecast in October that company tax receipts would crash from $127 billion this financial year to $100 billion in 2023–24. But now it’s May, and prices are still high. Treasury has had to upgrade this year’s forecast to $138 billion, and the worst it can come up with for next year is now $129 billion.

Don’t assume it will end in deficit: no one knows yet. The future will reveal itself, as it always does. We could be entering a new era of surpluses or slumping back to the old run of deficits. Treasury is no longer trying to guess those numbers. It just starts with a gloomy forecast, so the eventual reality will be better than we expected, and we’ll hail their boss, the treasurer, as a good economic manager.

That’s how governments want us to see them. An unexpected budget surplus, especially the first for fifteen years, is a gold star on the treasurer’s report card. Well done, Jimmy Chalmers!

And by and large, he has done well, on the macro front. This budget is far from perfect. But as Chalmers keeps pointing out, it had to balance the need for restraint to bring down inflation with the reality that a lot of Australians are experiencing big falls in real income, the economic outlook has darkened, and the worst is yet to come. And those who have won or lost will be voting on the government in two years.

Economists in the ivory towers of academia or Murdoch’s propaganda machine feel free to ignore the pain felt by less fortunate Australians, or the government’s reasons for doing something for them. In the real world, though, Chalmers is right: government, of whichever party, has to find a balance between these goals.

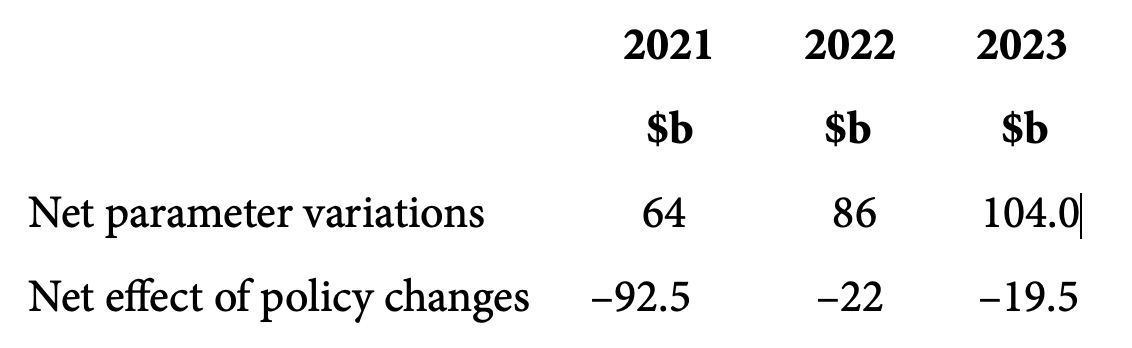

Here’s a concise comparison from the budget’s key table on macro matters: table 3.3 in budget paper 1. (“Parameter variations” are the changes in Treasury’s baseline estimates with no policy changes. And remember: by the 2021 budget, the economy was already roaring ahead, and by the 2022 budget, inflation was emerging as an issue):

Neither side would appreciate the comparison, but the balance Labor struck this time is remarkably similar to that of Josh Frydenberg’s budget a year ago. He banked 75 per cent of his windfall gains from Treasury’s upgraded bottom line; Chalmers has banked 81 per cent of his. Frydenberg was facing an election two months later; Chalmers is facing a more difficult economic situation.

An important note. The net effect of policy changes is not “new spending” as our ABC mates keep mislabelling it, but new spending minus new revenue. For the four years, the budget estimates a net $41.4 billion of new spending, only partially offset by $21.9 billion of net new revenue.

Chalmers points out that $7.5 billion of that new spending was required to correct unfunded or underfunded commitments left by the Coalition government, including underfunding our biosecurity program, digital health infrastructure, the Brisbane Olympics and Canberra’s national institutions. (While the War Memorial was given a $500 million expansion, all the other cultural institutions were starved by the Coalition, perhaps to pay for it.)

After perusing the departmental expenses table in budget statement 4, I doubt that Labor has dealt with all the underfunding. Excluding the National Disability Insurance Agency, the budget assumes that the cost of running departments and agencies will grow on average by just 2.8 per cent annually over the four years, down from an annual average of 5.3 per cent over the last four years. I’ll believe that when I see it.

There are lots of spending cuts in this budget, though relatively few are specified. The government says its two budgets so far have achieved almost $40 billion of “savings and spending reprioritisations.” We’ll come to them later, but the allusions to them in the budget papers are full of management speak: there are no “spending cuts,” just spending “efficiencies” or “streamlining and modernising.” Using that language must make cuts easier on the cutters.

Still, Treasury estimates that this budget restraint will have a significant impact. In the past three years, it estimates, public demand in real terms grew by 18.9 per cent. In the next three years, it is forecast to grow by just 5.3 per cent — about the same as expected population growth. Three years of zero growth per head in public spending will be a big brake on the economy.

While we’re on the macro issues, three important things to note. First, the mix of higher commodity prices, high job growth and strong GDP growth has caused a dramatic improvement in the budget outlook, even through Treasury’s gloomy binoculars. And that has dramatically changed Australia’s debt outlook.

Instead of gross federal government debt peaking in 2030–31 at 46.9 per cent of GDP, Treasury now forecasts it will peak in 2025–26 at 36.4 per cent. That’s a big turnaround, and if it happens a great relief that increases our ability to cope with future shocks.

Second, be aware that, like the International Monetary Fund, Treasury thinks worse times are on the way. Retail sales — which had been way above trend in 2022 — are now falling as higher interest rates bite. Employment growth is forecast to shrink to 1 per cent a year for the next two years: that implies only a third as many new jobs will be created as in the past two years. Unemployment would rise, and real GDP growth would fall to just 1.5 per cent in 2023–24 and 2.25 per cent the following year. Those forecasts sound plausible.

Finally, Treasury predicts a ray of sunshine on wages. By the first half of next year, it believes, wages will be rising faster than prices, giving Australian workers their first growth in real wages for four years. But even if that is right — and Treasury has often overestimated wage growth in the past — real wages will have fallen 7.5 per cent in that time. It’ll be years before Australian workers get back to where they were before Covid.

Treasury predicts that inflation as measured by the consumer price index will decline to 3.25 per cent by the middle of next year — helped by several budget measures designed specifically to lower the CPI. That could mean less reason for the Reserve Bank to increase interest rates. But while the Reserve might ignore these budget tricks as it focuses on underlying inflation, the case for further interest rate rises now looks weak indeed.

The gloomy macro outlook makes it even more important to get the microeconomic policies right. On that score, this budget has big problems.

Labor is selling its budget as a package of measures designed to provide “cost-of-living relief” targeted to “looking after the most vulnerable.” It does some of that, but only sporadically, where it has spotted an opportunity that appeals to it.

Until the last fortnight or so saw a clamour of protest against its decision to ignore the report of its Economic Inclusion Advisory Committee urging a big rise in JobSeeker benefits, it’s clear that Labor’s only plan for JobSeeker was to move fifty-fives to sixties into the slightly less poverty-stricken category with those over sixty.

Labor’s moral and political antennae were askew. Anthony Albanese was lucky that he grew up in an era when to be poor in Australia meant the government gave you an austere but liveable income and cheap housing. That is no longer true. Albo needs to get back in touch with the angry teenager he used to be. The smug, rich sixty-year-old he has become might have something to learn from that boy.

At least the budget included a last-minute decision to lift the JobSeeker benefit by $20 a week. That’s $2.86 a day: there’s not much you can buy with that, and the budget offered no prospect of any further increases — not because it can’t afford them, but because it just doesn’t see the unemployed as a priority.

By contrast, under the stage three tax cuts — totally unmentioned in the budget papers, prompting News Corp journalist Samantha Maiden to dub them Voldemort — people with incomes of more than $200,000 a year will get an extra $25 a day. That’s more like the rise Labor’s expert committee said the unemployed should be getting. How can Labor claim it is focused on those “most in need”?

The budget papers estimate that the two changes to JobSeeker combined will cost $1.3 billion a year, in a budget of $700 billion a year. Questioned by Maiden yesterday, Chalmers implied Voldemort will initially cost $23 billion a year when it takes effect on 1 July 2024. It’s just a matter of priorities.

The government gave a better hearing to the inclusion committee’s second priority, an increase in rental assistance payments for the hard-up. They will rise 15 per cent, costing roughly $700 million a year.

And it went much further for single parents whose youngest child is aged between eight and fourteen: their benefits will rise from JobSeeker-level to pension-level — an increase of nearly $90 a week as against the $20 a week rise for those left behind on JobSeeker.

The story the spin doctors left for the budget itself was perhaps the best of all. Labor has finally acted to stem the flow of doctors out of general practice, which has seen more than sixty GP clinics close their doors in recent years, some leaving towns without doctors. But their way of fixing it, while interesting, might just backfire.

The GP crisis stems from the long freeze in Medicare rebates, begun by Labor’s Wayne Swan and continued for years by the Coalition. This effectively cut GPs’ incomes by about 25 per cent. Frydenberg ended the freeze, but it has never been made up, and only 11 per cent of new doctors now nominate general practice as their future career.

Health minister Mark Butler deserves our thanks for having listened, and persuaded his colleagues to act. But Labor won’t increase the rebates, which would have seen benefits flow to all patients. Instead, it will roughly treble the separate incentive it gives to doctors to bulk-bill.

This should more or less restore GPs’ real earnings, and see more patients treated for free. That in turn could reduce medical cost pressures on the CPI. Labor estimates that 11.6 million Australians will be able to get free (bulk-billed) care from their GP. But that also implies about fifteen million Australians will not. Watch this space.

Still, the biggest issue in health funding appears finally resolved. But the biggest issue in housing is getting further and further from a solution.

The budget forecasts that residential investment will decline 7.5 per cent in the three years to 2024–25 — at the same time as national rental vacancies have hit a record low of 1 per cent and advertised rents have risen by 10 per cent in the year to April.

Yet the budget simultaneously reveals that in the year just ending, population growth will exceed 500,000 for the first time. In the year about to begin, it is forecast to be close to another 500,000. In three years, almost 1.5 million more people will join us, yet housing is in record short supply, new construction is slumping, and every week builders are going broke.

Population growth mostly comes from net overseas migration, which is mostly under the control of the federal government. This is as bad a failure of policy coordination as I’ve ever seen.

The solutions are obvious: put the brake on immigration — especially since job growth is forecast to collapse — and put the accelerator on housing. This is now a crisis. The government should stop persisting with a patently inadequate target and funding mechanism, sit down with its crossbench critics and the industry, and work out solutions that fit the scale and urgency of the problem.

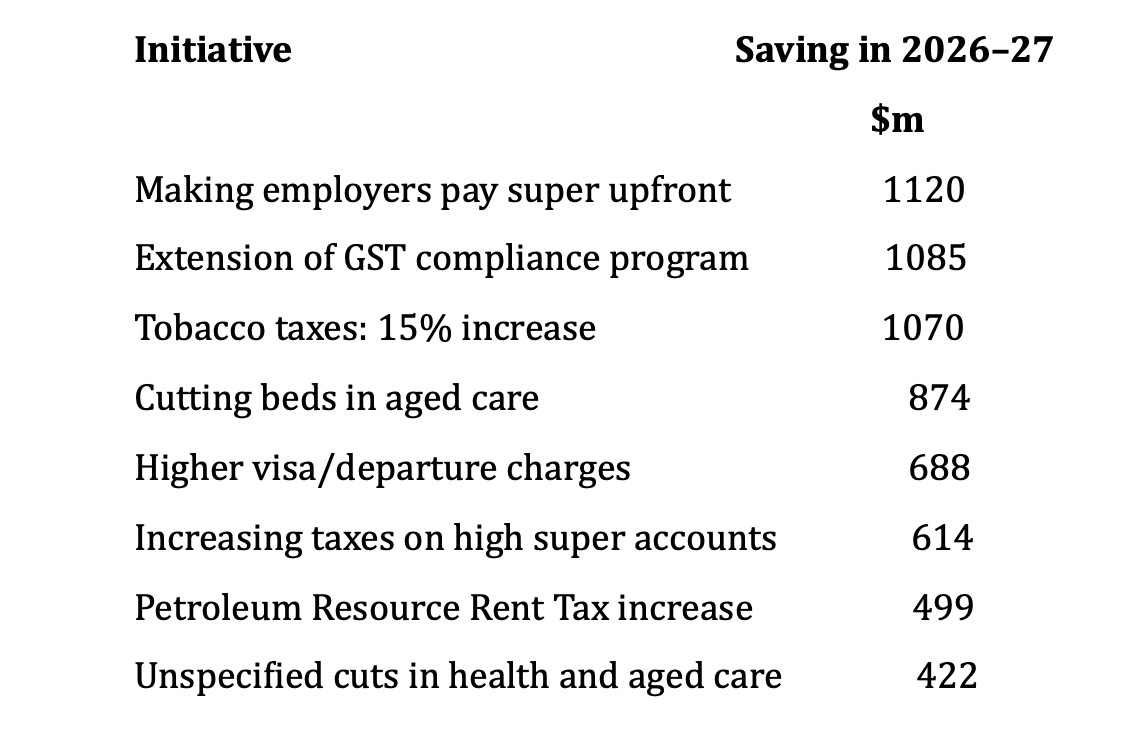

The other big problem with this budget is Labor’s fear of increasing taxes, which are far below the levels of comparable countries overseas. Just read the list of its “major budget improvements”:

The government is still frightened to impose significant new taxes on business, or any tax on “ordinary Australians.” Instead, it targets groups with no voice in public debate, like smokers and tourists. Yet many of the “most vulnerable” Labor wants to look after are smokers: the household expenditure survey shows smokers tend to be older and lower-income. Labor has hit them more heavily than the gas companies that make huge profits but pay little tax.

Cutting government-funded beds in aged care facilities from seventy-eight to sixty places per thousand people received little budget coverage. It’s one way of responding to staff shortages and “the increasing preference of older Australians to remain in their homes,” but it looks like a cynical move. It is expected to save eight times more than Labor’s extra spending on home care.

This budget is like a house with an impressive framework, built in difficult conditions, but puzzling in its detail. The further you explore inside this apparently attractive home, the more worried you become. •