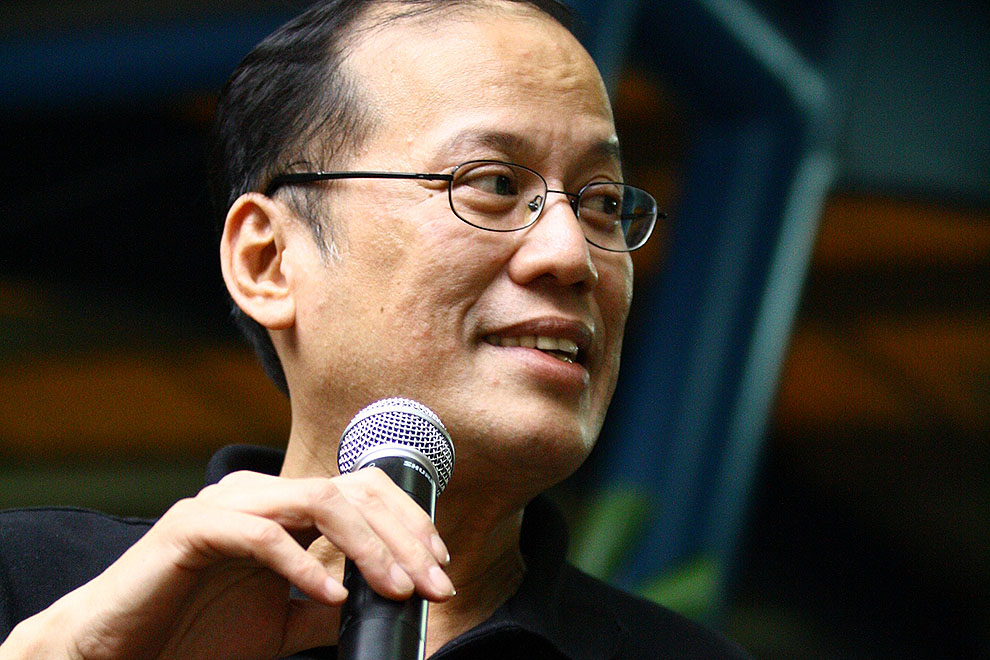

Benigno S. Aquino III – better known as Noy Noy or, since he became president four years ago, PNoy – has entered the final third of his six-year term with declining opinion poll ratings. After a remarkable four-year run of high approval and trust, the latest polling largely reflects his administration’s performance in dealing with corruption, an issue that dominated his campaign for office back in 2010. A year into a prolonged scandal involving the misuse of congressional funds, the public is yet to be convinced that PNoy has been resolute in pursuing those who have misused government funds, especially allies of the president identified as having colluded with bogus non-governmental organisations.

On top of that, PNoy and his budget secretary are accused of misusing the Disbursement Acceleration Program, a scheme deployed during 2011–13 to move savings within the national budget to other “fast-moving” programs and projects. In early July 2014, the Supreme Court ruled that the program was partly unconstitutional, a decision seen by some pundits as proof that the president had abused his prerogatives by disbursing sizeable portions of the budget to favoured groups and allies.

The Court’s decision limits the government’s capacity to use savings in Congress-approved programs to areas where more resources are needed within the fiscal year, a practice that PNoy and his allies argue had made government more responsive to the needs of constituents. More than this, though, the decision means that the president and other decision-makers could be called before other tribunals to explain whether their actions were undertaken in good faith.

Defending his actions in a televised statement to the Supreme Court in mid July, President Aquino tackled the Supreme Court head-on. “We do not want two equal branches of government to go head to head, needing a third branch to step in to intervene,” he argued, referring to the dispute between the Executive and the Court, and the prospect of Congress intervening. “We find it difficult to understand your decision. You had done something similar in the past, and you tried to do it again.”

What exactly the president expected from Congress wasn’t clear. Since then, however, his allies in the Lower House have started scrutinising the judiciary’s use of its own development funds, labelling them as “judicial pork.” One of PNoy’s allies even proposed that all Supreme Court justices should be impeached, an idea that thankfully was quickly scuttled.

A month after the televised statement, the drama intensified when PNoy appeared to significantly moderate his objections to a constitutional change that would allow him to serve a second term, which the constitution currently prohibits. Although it has been rumoured for some time, such a plan – referred to as charter change or, in inimitable Philippines style, Cha-cha – has only recently been treated seriously. He had reconsidered his position on Cha-cha, he said, chiefly because he saw a need to restore the checks and balances in the relationship between the branches of government, and specifically to review and possibly clip the power of the Supreme Court.

Basketball is the most popular spectator sport in the Philippines. In a country where players normally lack the height and heft to compete successfully with teams from other nations, the sport’s large following can partly be explained by the personal appeal of individual basketball stars, some of whom have even catapulted from the court to the political playing field.

So it’s not surprising that the president of the dominant party, PNoy’s Liberal Party, uses a basketball metaphor to describe his party’s strength and the support from within to push PNoy to seek a second term. Responding to a question about whether the Liberal Party was open to having PNoy as its standard-bearer once again, party president and transport secretary Jun Abaya described the president as “our best player,” though he also claimed that the party’s “bench is deep.”

Before the lifting of the single-term restriction was floated, interior secretary Manuel “Mar” Roxas – whom Abaya called the Liberal Party’s “second best player” – had been regarded as the party’s likely contender for the presidential race in 2016. A former senator whose grandfather founded the Liberal Party, Roxas had been slated to run in 2010, but gave way to Aquino and instead contested the vice-presidency. When he lost, PNoy appointed him to cabinet, first as transportation secretary and later to the interior and local government portfolio. Interestingly, the proposal to allow PNoy to extend his term was first broached by Roxas himself.

PNoy has yet to clarify his views on constitutional changes in general, and on the question of a second presidential term in particular. In mid August 2014, he said that he will listen to the views of his “bosses” on whether he should seek a second term. Asked what he will do on the day after his term ends, he said that he and his closest colleagues “will eat delicious food while there’s a streamer posted behind… with the word: Freedom.” If he does eventually decide to seek a second term, however, the constitutional change will have to clear a number of obstacles.

The first obstacle is the leadership of Congress. While a few of his Liberal Party colleagues have vocally supported the lifting of the single-term restriction, the leaders of both houses of Congress have been noncommittal or have rejected the changes. The Senate president, Franklin Drilon, has said any move for change would deflect attention away from other priority measures. The Lower House speaker, Feliciano Belmonte, opposes any such amendment outright. Without congressional support for a resolution, or for the creation of an appropriate venue to deliberate on the change, the two-term plan will go nowhere.

A second and even bigger obstacle will be public support. Though PNoy still retains the approval and trust of a majority of the public, the significant decline in his opinion poll rating this year indicates waning political capital for the president. Pushing for constitutional change may cause these ratings to decline further and generate broad opposition to a seemingly self-serving measure. This kind of opposition has certainly emerged in the past, against Ferdinand Marcos in 1971, Fidel Ramos in 1997, and Gloria Macapagal Arroyo in 2005.

President Ramos’s experience is particularly instructive for PNoy. In 1997, individuals and groups close to the president initiated a signature campaign to amend the single-term limit. This initiative, the People’s Initiative for Reform, Modernisation and Action, or PIRMA, was primarily driven by the desire to fend off a possible win in the 1998 presidential elections by Ramos’s popular deputy, Joseph Estrada. Interestingly, the argument used by PIRMA – that reform can only be sustained if the president is allowed a second term – is the same refrain sung by those currently pushing for constitutional change. Unfortunately for Ramos, the opposition against PIRMA was broad, uniting key figures from all political camps, including Estrada, Manila’s Cardinal Jaime Sin, former president Cory Aquino, and Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, who was a senator at the time. Should allies of PNoy push for change, a similarly strange set of bedfellows is likely to rally in opposition.

Among the likely motives for the proposal to allow PNoy to run again is the belief that he is the only Liberal Party figure who can give the current frontrunner in the presidential race, vice-president Jejomar “Jojo” Binay, a run for his money. The same fear that enveloped supporters of Marcos, Ramos and Arroyo, the fear of losing control of government, appears to be afflicting the members of the dominant party, and this fear is not without basis.

In a recent early poll measuring voting preference for the 2016 presidential elections, the Liberal Party’s “second best player,” Roxas, was trailing, tied at fourth place on 7 per cent, on a list of eleven possible presidential candidates. While it is still too early to rule out the possibility that Roxas’s support base could expand significantly, this dismal standing has led some supporters to look at alternative candidates, the incumbent president included. The claim that the Liberal Party’s bench is deep is clearly belied by the early poll: aside from Roxas, the only other Liberal Party member on the list is Senate president Drilon, whose support is a mere 1 per cent.

Meanwhile, Jojo Binay has the support of 41 per cent of polling respondents. This partly derives from the high approval and trust ratings he retains as a member of PNoy’s own cabinet, where he holds two portfolios, as head of the Housing Coordinating Council and presidential adviser on Overseas Filipino Workers’ concerns. Despite having run on a different party slate for the vice-presidency, Binay is a close friend of PNoy and his family. Former president Cory Aquino, PNoy’s mother, appointed Binay to his first government post, as acting mayor of Makati, the central business district of the country’s capital, in 1986. Binay has remained close to the Aquinos, and especially to the president’s sisters – close enough to have allegedly obtained their endorsement in the vice-presidential race of 2010 and their early support for the 2016 presidential race.

Binay’s electoral strength may also be a product of connections he built up among other local politicians during his long tenure in Makati. Looking every bit the ordinary Filipino, Binay also connects easily with the regular voter. The remarkable performance of his daughter Nancy, a political neophyte, in the 2013 senatorial race – fifth place in a race that included seasoned contenders – provides further evidence of his electoral pull. Given his current electoral support, however, he has inevitably become the subject of allegations, the most important of which concern an allegedly overpriced building he constructed when he was mayor.

The only other prospective candidate with double-digit support – though a much lower 12 per cent – is relative newcomer Grace Poe. Currently an independent, Poe ran as a guest candidate in the Liberal Party coalition for the senatorial elections of 2013. Her electoral support is partly rooted in the popularity of her father, the late actor and 2004 presidential candidate Fernando Poe Jr, known as FPJ. As the opposition presidential candidate in 2004, FPJ lost to the incumbent, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, probably as a result of cheating widely believed to have been orchestrated by groups allied with Arroyo. That view of the campaign was reinforced in mid 2005 with the leaking of a pre-poll recording of a conversation between Arroyo and an official of the Commission on Elections. Known as the Hello Garci tape – Garci being the nickname of the official, Virgilio Garcillano – it records Arroyo issuing instructions for her vote to be padded by at least a million. So far, Grace Poe has performed remarkably well as a senator, including playing a key role in the passage of freedom of information legislation.

Former president Joseph Estrada takes the third spot in the polls, but it is highly unlikely that he will run for the post for the third time. It is still too early to ascertain who else might eventually throw their hat into the ring. Even Binay’s current level of support is bound to change, especially given the new accusations that he behaved corruptly as mayor of Makati.

What will count for PNoy and his supporters, however, will be the state of the economy and politics over the next two years. The president will need to be more attentive to urgent policy concerns rather than jumping on the Cha-cha bandwagon. If he really is the best player on the team then he needs to begin the transition to the role of a coach and not be swayed to take on yet another term as star player.

If the Liberal Party president really wishes to employ sports metaphors, he and his party should heed the lessons of all winning teams and strive to work as a cohesive group. Philippine parties have historically been candidate-oriented rather than policy-oriented, mere vehicles for personalities to vie for elective office. So far, under PNoy, the Liberal Party has retained these characteristics.

As a professional basketball game in the Philippines draws close to an end, it is customary for the coliseum barker to announce that the game has entered the “last two minutes.” PNoy has entered into his last two years and it may be best for him to focus on institutionalising changes in administrative processes through the passage of statutes rather than venturing into the risky process of changing the rules of the game. •