Two scholarship boys, both born in 1894, both drawn to politics and the law, were destined to be fierce rivals on the national stage. Running for the Nationalist Party in 1928, one of them — Robert Menzies — secured election to the Victorian upper house; the following year he moved to the lower house and then in 1934, with the United Australia Party, to federal parliament. The other — H.V. “Doc” Evatt — resigned from NSW parliament to join the High Court at the unlikely age of thirty-six; even more unlikely was his decision to quit the bench in 1940 to run as a Labor candidate in the federal election.

Evatt’s move from court to federal parliament was considered “a most regrettable precedent” by Menzies, who was by then prime minister. (While it may have been regrettable, it wasn’t much of a precedent, never being repeated over the ensuing eighty-three years.) Evatt responded in kind, suggesting that Menzies would lose the next election. (That, too, proved a less than accurate prediction.) As Anne Henderson sees it in her new book, Menzies vs Evatt: The Great Rivalry of Australian Politics, battle was joined from that time.

Reading Henderson’s opening chapters it’s hard not to be staggered by Evatt’s workload as external affairs minister and attorney-general. No minister today would take on these dual roles, and Henderson highlights the difficulties the combination caused for Labor in government, especially at a time of war.

It would have been a punishing load for the best-organised minister (which Evatt clearly was not), and was exacerbated by his frequent absences overseas in the pre-jet age, including a year as president of the UN General Assembly. As an often-absentee attorney-general, he was unable to contribute fully to vital tasks, including defending the government’s bank nationalisation plan before the High Court.

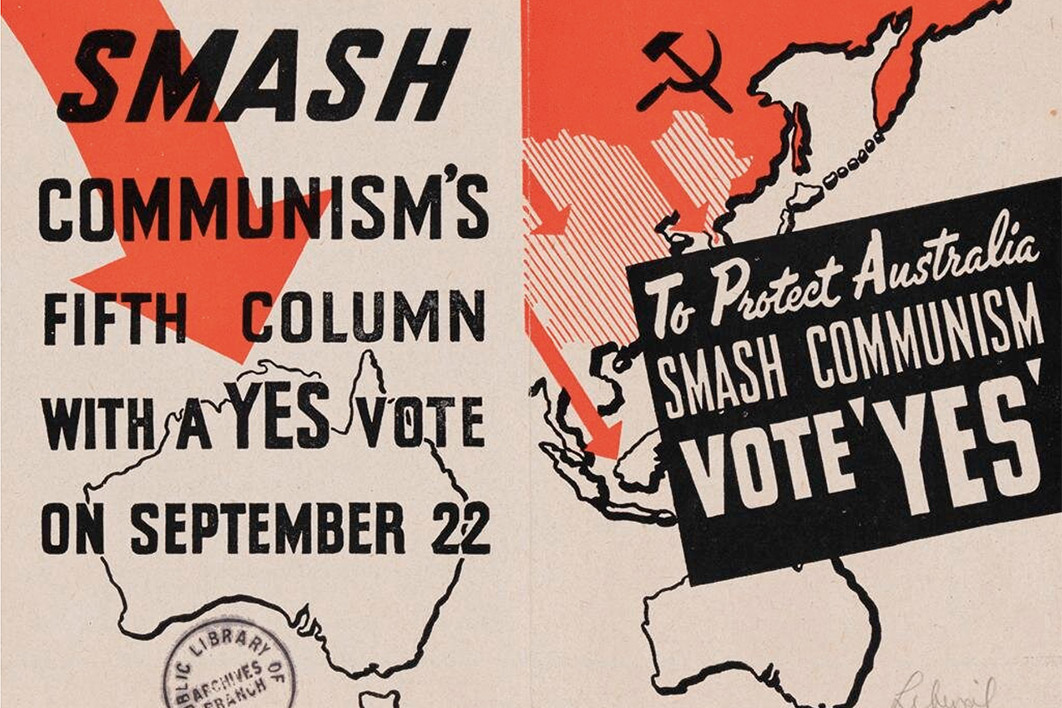

Evatt became Labor leader after Ben Chifley’s death in June 1951. His role later that year in defeating Menzies’s referendum to ban the Communist Party is seen by many as his finest moment, but Henderson downplays the victory. Support for the ban was recorded by polls at 73 per cent in early August but by polling day, six weeks later, it had dropped to just under 50 per cent. (The referendum was carried in only three states.) Henderson cites the history of defeated referendum proposals and asks why the Yes even got close — as if falling support for the ban followed a law of nature regardless of effective political campaigning.

It’s true that early support for many referendum proposals has evaporated by polling day. But it is difficult to think of a question for which Yes campaigners enjoyed more favourable circumstances than this one. The cold war was in full swing, Australian troops were fighting the communists on the Korean peninsula (under a UN flag), and communism was seen as an existential threat, broadly detested within the electorate. Menzies had warned of the possibility of a third world war within three years; strong anti-communist elements within Evatt’s own party supported the ban.

Indeed, one might equally ask why Menzies couldn’t pull it off. I suspect that he would have appreciated the irony that it was the internationalist Evatt, not the Anglophile Menzies, who campaigned by citing British justice’s onus on the state to prove guilt rather than (as the anti-communists proposed) on the accused to prove innocence.

As with most failed referendums, the loss did the prime minister no harm. In fact, Henderson makes the interesting suggestion that it saved him from having to enact legislation that may “have been as divisive and unsettling to civic order” as the McCarthy hearings were in the United States. It’s impossible to prove of course, but Australia definitely didn’t need that kangaroo court–type assault on individuals’ reputations and lives.

Henderson’s account of the Petrov affair and the subsequent royal commission — a disastrous time for Evatt — traverses territory that is probably less contentious than it was a generation ago. On the Labor Party’s 1955 split, she quotes with approval the claim by former Liberal prime minister John Howard that Labor’s rules afforded too much power to its national executive: a more genuinely federal structure (like that of the Liberals) would have rendered Evatt’s intervention more difficult and a split in the party less likely.

Whether a Victorian Labor branch left mostly to its own devices would have sorted out its problems is unclear, but the opportunity was unlikely given the hostility of Evatt and his supporters to the group of Victorians they saw as treacherous anti-communists. Ironically, it was this capacity to intervene that would facilitate a federal takeover of the moribund (and still split-crippled) Victorian ALP fifteen years later. That intervention eventually reinvigorated the state branch, establishing a Labor dominance in Victorian state elections and in the state’s federal seats that persists to the present day.

Henderson also poses the question of whether a different Labor leader could have avoided the split. What if deputy leader Arthur Calwell had been installed after the 1954 election loss? She speculates that Calwell might have been able to offer concessions to the anti-communist Victorians and stresses an absence of intense ideological fervour among many of those who would soon be expelled from the party.

While it is hard to envisage a leader handling the crisis less effectively than Evatt did, Henderson quotes Labor MP Fred Daly’s view that Calwell at the time was “hesitant, uncertain and waiting for Evatt’s job” — hardly the stuff of firm leadership. Arthur was always prepared to wait.

It may be true that most of the anti-communist Labor MPs, even in Victoria, were not fervent ideologues, but possibly more relevant was the ideological predisposition of the powerful Catholic activist B.A. Santamaria, who was able to influence state Labor’s decision-making bodies and preselections from outside the party. Santamaria boasted in 1952 to his mentor, Archbishop Daniel Mannix, that his Catholic Social Studies Movement (the infamous “Movement”) would be able to transform the leadership of the Labor movement within a few years and install federal and state MPs able to implement “a Christian social program.”

This may have been overly ambitious nationally, but Santamaria’s undue influence over Victorian Labor was already a concern for some. Moreover, the party Santamaria envisaged might be viewed as essentially a church or “confessional” party, at odds with traditional Australian “Laborism,” not to mention with the main elements of a pluralist, secular democracy.

Henderson’s most interesting observation, for this reviewer, is her contention that Evatt’s lack of anti-communist conviction owed much to his being “an intense secularist.” It is certainly the case that critics of communism in this era often preceded the noun with the adjectives “godless” or “atheistic.” In a predominantly Christian society like Australia, communism’s atheistic nature was a damning feature, especially among Catholics, including Catholic Labor MPs. Presbyterian Menzies also held strongly to this view.

If this review has focused more on Evatt than on Menzies, this reflects the enduring questions Evatt’s leadership raises — including the state of his mental health, which is seen by some as helping to explain his erratic and self-destructive behaviour. (Henderson doesn’t consider this question, but it was well covered by biographer John Murphy.)

Menzies, having survived the referendum result, was also undaunted by his narrow election victory in 1954, secured with a minority of the vote, a lucky escape to be repeated in 1961. He went for the Evatt jugular whenever it was exposed — which was often, as Henderson shows vividly. John Howard would later claim, on his own behalf, that the times suited him. Menzies had that advantage in spades, and he exploited it artfully.

If there is a central theme to Menzies’s approach to his battle with Evatt, it is his characterisation of the Labor leader as a naive internationalist, oblivious to the emerging threat of monolithic communism, especially to the north of Australia. This is a criticism endorsed by Henderson. A cynic might suggest that the communist threat was not only electoral gold for Menzies but also provided a convenient pretext for him to maintain his unwavering support for European colonialism. Better the colonialists than the communists.

Neither character was a team player by instinct, but Menzies adapted better and learned from mistakes. Among other flaws, Evatt’s lack of self-awareness was both crucial and crippling. There is no doubt that the winner of the “great rivalry” was Menzies.

As a known partisan, Henderson runs the risk that her book will be seen in that light, and that her put-downs of Evatt’s admirers — “a collective of scribblers,” “the Evatt fan club” — will be viewed accordingly. Her failure to acknowledge any merit in Evatt’s referendum victory will seem churlish to some. But Henderson can’t be faulted on the book’s readability: it’s a one-sitting job for those fascinated by the politics of that era.

I was left wondering about the depth of the personal animus between the two men. Henderson quotes Menzies accusing Evatt of being too interested in power — as “a menace to Australia” to be kept out of office “by hook or by crook.” Prime ministers and opposition leaders routinely find themselves in settings where some form of civil, non-political conversation is virtually unavoidable. What on earth might these two have talked about? Well, both of them loved their cricket. •

Menzies vs Evatt: The Great Rivalry of Australian Politics

By Anne Henderson | Connor Court | $34.95 | 236 pages