Accepting the inaugural Aspen Award for Services to the Humanities in 1964, the composer Benjamin Britten spoke of “this holy triangle of composer, performer and listener.” It’s a good line, and one I’ve trotted out myself from time to time, especially in order to make the point that music doesn’t really exist unless it’s being heard.

A composer may work for weeks, months or sometimes years to polish up a score, but the music remains silent on the page until brought to life by a performer or performers. This bringing to life is itself interesting, because it is essentially the same for a thirteenth-century motet as for a brand-new composition: in performance, all music is made new.

Something similar might be said of the listener’s role. If there’s no one to receive the music, the musical experience is incomplete. It’s not quite the tree falling in the forest, because the performer is also a listener, but a non-performing listener brings something else to the music, and it’s another form of participation, as Britten stressed in that Aspen speech.

Good listening, he said, “demands some preparation, some effort, a journey to a special place, saving up for a ticket, some homework on the program perhaps, some clarification of the ears and sharpening of the instincts.” It’s all true.

And yet Britten’s triangular formula only holds for notated music, where the composer and the performer are different people. It doesn’t cover improvisation, the spontaneous composition of music in which intense listening by the performers will dictate the next note.

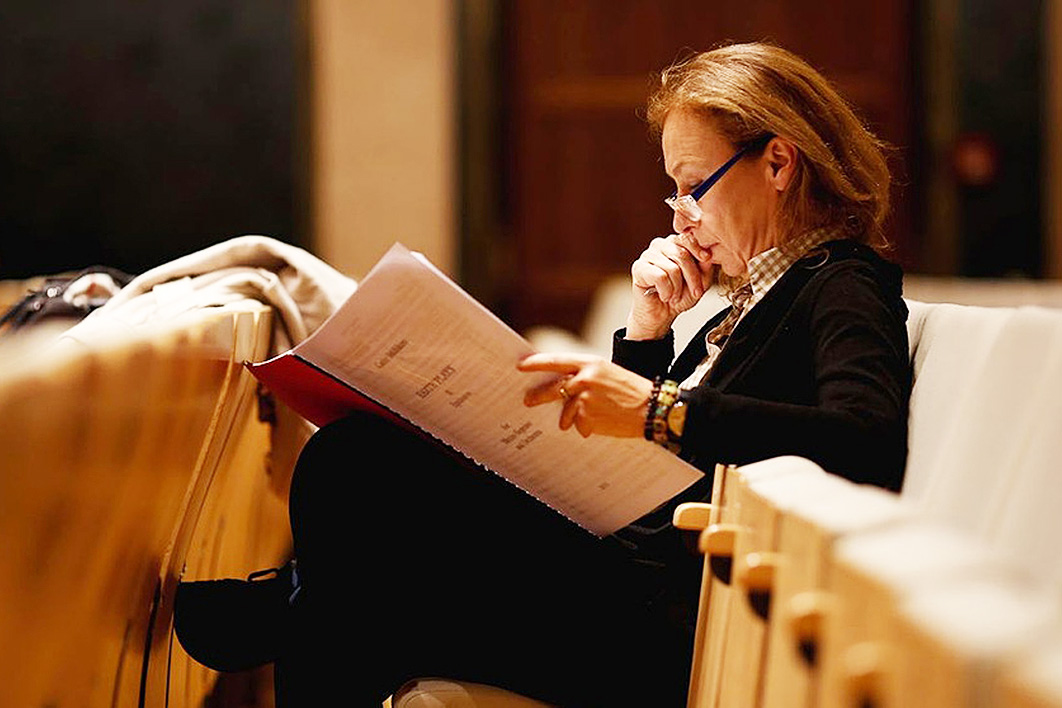

Two Step, by the Australian oboist and composer Cathy Milliken, certainly throws a spanner in the works of Britten’s theory. Long resident in Germany, Milliken collaborated with friends and colleagues from Brisbane, Berlin and Tel Aviv — players and singers, most of them also composers — to create a continuous span of seemingly evolving music. When the recording appeared at the start of the year, the producers of The Music Show on Radio National attempted to find a four- or five-minute section to play on the radio, but there’s really nothing that makes much sense as a standalone item: to do it justice, you must hear the whole, or at least a very long stretch. This is remarkable, given the circumstances under which the music was made.

The work comprises a series of duets between Milliken’s oboe and Sören Birke’s duduk, Milliken’s oboe and Vanessa Tomlinson’s percussion, Milliken’s oboe and Brett Dean’s viola, Milliken’s cor anglais and Carol Robinson’s clarinet; but also between Tomlinson’s percussion and Julian Day’s organs, Tomlinson’s vibraphone and Dietmar Wiesner’s bass flute, Wiesner’s flute and Dean’s viola: it’s like a chain. The duos, a mix of notated sketches and improvisation, were all recorded separately, then edited, juxtaposed and overlapped. The end result is music that flows from moment to moment. Except when it doesn’t.

Listening to this piece can seem like eavesdropping on a series of intimate conversations — not quite what Britten had in mind — though there are also moments when we are called to attention, when the music doesn’t flow so much as stop us in our tracks.

The first of these is the entry of William Barton’s didgeridoo, its glorious sonority overwhelming the nearby viola and cor anglais. Something similar occurs when Wu Wei’s sheng plays. When we hear the flute or the vibraphone for the first time in Two Step, we register that a new instrument has appeared in the piece, that a new sound has been added to the mix. Barton’s didgeridoo and Wu’s sheng come freighted with cultural significance we can hardly ignore and they grab our attention. Perhaps that’s why Milliken used them sparingly in her final assembly of the component parts.

Then there are the voices, singing and speaking. The spoken words are from poems in Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons (1914), read by Day, Tomlinson, Dean and Milliken herself. The composer explained to Shirley Apthorp in the sleeve note accompanying the Tall Poppies album that she incorporated the poems in her musical landscape because she “was interested in seeing whether the texts stand out or merge with the music.” She concludes that they do both.

At first, I wasn’t so sure. When you hear words, particularly Stein’s rather inscrutable texts, you try to comprehend them. And the speaking voices are generally in the foreground, adding to this inevitability. But one day I found myself, by chance, listening to the album with the volume very low. I could still hear the voices, but only as murmurs. The words were indiscernible, the voices now fully part of the music.

Where does all this leave Britten’s triangle? In Two Step, the roles of composer and performer are blurred, but the listener — and this includes Milliken and her colleagues, as well as you and me — is more important than ever. Any piece of notated music is made first by its composer, then by its performers, then once more in the listener’s head. Even a piece such as Britten’s War Requiem, which we might know well, is remade each time we hear it, affected by what we’ve listened to and possibly read in the time since our last encounter with it, what we heard just yesterday, and how we’re feeling today. Sometimes one is simply not in the mood.

But Milliken’s Two Step, which its composer assembled from fragments of musical ideas — many of them the performers’ ideas — and which retains a somewhat provisional air, requires more of us. We must bring our imaginations to the project, as well as our experience of Western and non-Western instruments and our ability to parse Stein’s writing. It’s hard, indeed, not to feel that we are, to some extent, composing the music ourselves. And with that, Britten’s triangle collapses. •