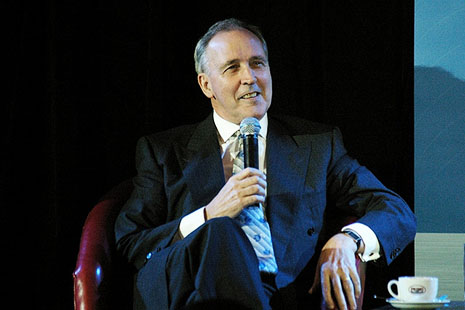

IT IS now clear that the union movement made a bad mistake when it backed the introduction of the compulsory superannuation scheme devised by Labor’s Paul Keating, urged on by the ACTU secretary at the time, Bill Kelty. To this day, there is still no detailed policy report showing that net economic and social gains flow from forcing employees to hand over a growing slice of their salary to the richly rewarded fund managers in the nation’s booming financial sector. Appointed by the super fund trustees to “invest” the money, these managers usually focus on taking huge punts on the financial markets. Simply swapping the ownership of existing shares and fancy financial derivatives between fund managers and other market players creates little of economic value, however – unlike direct investment in productive new capacity.

Several younger union officials now say privately that they believe the majority of their members would be better off if compulsory super contributions were paid instead as a normal part of salaries, letting all employees decide how best to allocate their income over the course of their working life. Many could make a well-reasoned decision to enjoy a better standard of living while working rather than forgoing income now in an attempt to have extra money in their old age.

Given a choice, many members of the workforce would probably put more money into raising a family, paying off a mortgage, upgrading their educational qualifications and so on. But compulsion robs them of that choice. The cost of the tax concessions for super – heavily biased towards high-income earners – also robs the government of tens of billions of dollars a year that could enhance well-being by funding tax cuts, education, child care, health and transport infrastructure.

Some older union officials like to portray money diverted compulsorily to super as a free gift from employers. It is not. It is money that could otherwise be paid as wages – a point that the superannuation minister (and former Australian Workers’ Union secretary) Bill Shorten candidly acknowledges. Everyone is compelled to put 9 per cent of their salary into a super fund, and now, despite financial sector lobbyists having given up hope of winning an extension of compulsion, the Labor government has decided to lift contributions to 12 per cent.

If the government decided instead that employers should pay the existing 9 per cent as part of a normal salary, this would boost by $43.60 the take-home pay of someone on the minimum wage of $570 a week. Those on average weekly earnings of $1260 a week would get around $80 extra; those on $1800 a week would get an extra $102.

Although it’s easy to dismiss this option as too politically difficult, boosting disposable income by scrapping compulsory super could prove electorally popular with households that find it hard to make ends meet. Everyone would still be free to contribute to super, which, as discussed below, could remain an attractive savings vehicle for many Australians. But the finance sector would scream that the end of compulsion would mean that people would not have “enough to live on” in retirement.

No one is suggesting that saving should be forbidden – merely that people should be free to decide how much they want to save and in what form. There is no reason to believe that retirees won’t continue to own more assets, on average, than those still working. Without compulsion, even low-income earners would still be likely to accumulate assets, often in the form of their home, and be eligible for the age pension. In terms of what the government considers “enough,” the age pension sure beats the Newstart Allowance paid to those who lose their job; at present, the single rate for the age pension is $123.20 a week higher.

In any event, many people don’t feel they have “enough” to live on while working – a period when their expenses are usually higher than in retirement. If they prefer to get access to more of their income while they’re working, mainstream economics suggests that the choice should be left to them. The finance sector would argue that the cost of the age pension would rise if less money went into super. But, as the Henry tax report makes clear, the combined budgetary cost of the age pension and the tax concessions on super rises with increased contributions. If you want to save the budget billions of dollars – and increase take home-pay – scrapping compulsory super is the way to go.

The performance of the fund managers over the past decade hardly suggests that governments should force people to give them another cent. The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority recently released figures showing that the average nominal annual super fund return over the ten years to 30 June 2011 was a pathetic 3.3 per cent. Given that the average annual increase in the CPI over that period was 3.2 per cent, returns only beat inflation by the slimmest of margins. Australians would have been better off putting their money into government bonds and term deposits, or reducing their mortgage or upgrading their educational qualifications or those of their children.

Returns from super might improve over the next ten years. Then again, they might not. Contrary to the nonsense peddled by supporters of the efficient markets hypothesis, no one knows what will happen to financial prices in a radically uncertain future. As an assistant governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia, Guy Debelle, explained in a speech on 31 August last year, a key problem in the recent financial crisis stemmed from the financial world’s failure to accept the distinction between risk and uncertainty made early last century by two economists, Frank Knight and John Maynard Keynes. In Debelle’s assessment, financial institutions and regulators mis-assessed risk by ignoring Knight and Keynes’ convincing conclusion that risk is quantifiable and uncertainty is not. “Ultimately,” Debelle said, “the future is uncertain, in the sense that it cannot be quantified.” In these circumstances, it is hard to see how governments can justify compelling Australians to hand over a significant slice of their income to super funds whose future returns are inherently uncertain.

But the government remains committed to compulsion and to the recommendation of Jeremy Cooper’s review of Australia’s super system that all funds be obliged to adopt a “forward‐looking, risk-targeting framework” to “provide members with a proper indication of expected future returns.” Cooper is demanding the impossible.

Once tax obligations have been met, policy-makers usually prefer to let people decide for themselves how to allocate their income. But compulsory super seems to be generally accepted – without any solid back-up analysis – as a “good thing.” Nevertheless, some Liberal party politicians are starting to wonder how compulsion fits into their philosophical framework of supporting individual liberty. The finance sector’s massive lobbying power seems likely to ensure these doubts are not converted into policy.

Contrary to a key goal of the economic reform agenda in Australia, compulsion can distort the efficient allocation of resources. Thanks largely to government compulsion, fees paid to fund managers and administrators now amount to about $18 billion a year. Billions more will flow from the move to 12 per cent compulsory contributions. Other industries can only dream of receiving a similar leg-up. In effect, the government has ordered dump trucks to line up each morning and tip millions of dollars through the front doors of the super funds. Even the motor industry would willingly swap its generous assistance package for one in which the government decreed that all Australians must buy a new car from a local manufacturer every year, regardless of whether they had better things to do with their money.

In contrast to the silence of most other economic agencies, the Productivity Commission drew attention to the problems of compulsion – without specifically criticising Australia’s $1.2 trillion super system – in its recent draft report on aged care. “Compulsory saving imposes a deadweight loss as it distorts decisions about which savings vehicles to use, as well as between consumption and savings,” said the commission. “In particular, younger people may be less able to invest in their preferred mode of savings (for example, owning their own home, which is a tax effective savings vehicle and offers social benefits).”

The commission’s report also rejected calls to encourage extra savings for aged care by introducing the type of tax concessions applying to super. “Such subsidies,” it said, “perform poorly on equity grounds as they offer the greatest benefit to those with the greatest capacity to save (being also those most likely to have the capacity to contribute to their own aged care in the future).”

The tax concessions on super provide no advantages for those on incomes up to $37,000, but certainly help those on higher rates. At present, someone on the top tax rate of 45 per cent only pays 15 per cent on their contributions. The same rate applies to fund earnings before age sixty. Abolishing compulsion would mean that contributions would now come from after-tax income. If it were seen as desirable, incentives to contribute – including retaining concessional treatment for earnings in the fund – could be maintained.

Based on figures in Treasury’s tax expenditure statements, the increase in super contributions to 12 per cent is likely to cost the budget at least $8 billion a year when fully implemented in 2019. Even before then, the combined budgetary cost of the age pension and the super tax concessions is likely to hit an annual $100 billion. Yet the budget papers estimate that lifting compulsory contributions to 12 per cent of salaries will add a tiny 0.4 per cent to national saving by 2035. Left to their own devices, there is no reason why most people couldn’t do as well as that. •