For the tenth year in a row, the Australian National Audit Office, the agency that brought us the sports rorts affair and revealed that the federal government had massively overpaid for land in Western Sydney, had its funding cut in the federal budget.

The ANAO is not alone. Government funding for the Independent Parliamentary Expenses Authority, the information commissioner (who deals with freedom of information appeals), the Administrative Appeals Tribunal and the Commonwealth ombudsman have all gone backwards this year, too. These are some of Australia’s most important accountability agencies, and they’re shrinking.

When treasurer Josh Frydenberg was questioned about the ANAO cuts on ABC TV’s Insiders, he brushed them off as largely inconsequential. “The departmental appropriation is only $600,000 lower this year versus last year,” he said, “and importantly the average staffing levels are broadly similar as well.”

The treasurer is right to say that the funding cuts are not huge in dollar terms and that staffing has been roughly maintained. But this ignores a long history of cuts, year after year, to a small agency with little fat to absorb further savings.

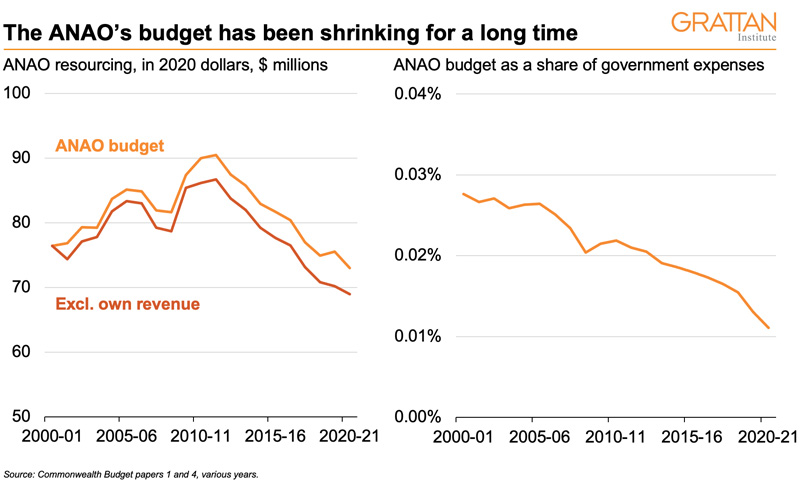

The ANAO’s budget has been going backwards for a decade. As a share of government expenditure, the pattern is even more striking: it has fallen for most of the past twenty years. It has more government spending to monitor, but fewer resources to do it.

The shrinking budgets for accountability agencies partly reflect a long-term trend of reduced spending on the public service. In office, both major parties have used an “efficiency dividend” to cut expenditure. This small annual reduction in operating expenses applies across almost all of the public service (with the notable exceptions of the National Disability Insurance Agency and most of the defence budget).

Efficiency dividends have been around for decades but have grown much larger in recent years. They apply budgetary pressure, which can encourage departments to continually seek new or more efficient ways of doing things. But they are a blunt tool that can punish agencies that are already running efficiently.

A 2008 review found that the efficiency dividend is especially punishing for small agencies like the ANAO that have more tightly defined functions and, thus, less flexibility to find savings. And because they are rarely involved in new policy, small agencies are also much less likely to be able to top up their funding by proposing new programs.

Before the 2020 budget, the auditor-general wrote to the prime minister pleading for additional resources. The ANAO has operated at a loss for the past couple of years and will (again) need to reduce the number of performance audits provided to parliament.

That means fewer reports like those that revealed the sports rorts and the Western Sydney land scandal. This might make life more comfortable for politicians and public servants, but it could embolden the type of maladministration seen in those cases.

Weakening the watchdog is an even bigger worry in the context of unprecedented post-pandemic government spending, including hundreds of millions for community infrastructure, capacity building and tourism-related infrastructure projects. These are exactly the types of political danger zones that benefit from scrutiny.

The plight of the ANAO also highlights a much broader problem. Accountability and integrity agencies must survive on budgets granted by the government of the day — the very governments whose programs they are set up to monitor. Australia needs a better way of providing adequate, secure and stable resourcing. In the first instance, the Productivity Commission should review the budgets of these agencies and provide guidance to parliament on a more appropriate and sustainable funding model.

When the government is shrinking the budgets of the few agencies that ask difficult questions — meanwhile attempting to justify its glacial progress on a federal ICAC — perhaps the only logical conclusion is that accountability isn’t high on its list of priorities. •