Fifty years ago, I witnessed Captain James Cook’s arrival on the shores of Botany Bay — or rather, a re-enactment of the event on one of the barren asphalt assembly grounds at Mona Vale Primary School. The bicentennial event involved a reconstruction of the Endeavour in the form of an awkward float, and some sort of confrontation with pupils cast as Aboriginal people. Such commemorations are supposed to foster feelings of national belonging, but my recollection is one of tedium and indeed alienation from the heroic perseverance our headmaster stressed in his address. Throughout my childhood, Cook seemed a statue rather than a story: a bearer of unachievable and even unattractive virtues rather than a life that was extraordinary or enigmatic.

Later, as a university student increasingly absorbed in the anthropology and history of the Pacific, I retained this sense of Cook as an indomitable but apparently one-dimensional explorer, a man who wanted only to put lines on a map. Beginning research on the Marquesas Islands, I was fascinated by a drama of shamanism, taboo, tattoo, unfamiliar gender relations and cross-cultural exchange. Even as I began reading mariners’ journals for what they revealed of early encounters, Cook, the most celebrated of them, seemed a fixture of national histories rather than a character who might himself be an actor or locus of interest. Yet I was surprised when I read his account of first contact at Kamay, or Botany Bay, where the Endeavour’s crew was famously resisted by the Gweagal. After the seamen had tried fruitlessly to initiate relationships with local people, Cook candidly acknowledged, “it was to no purpose, all they seem’d to want was for us to be gone.”

I was still more surprised, a few years later, to come across a monumental but obscure book by one of the participants in Cook’s second voyage. Joseph Banks had been expected to again accompany Cook, this time on an expedition that sought to establish once and for all whether any southern continent existed. But Banks wanted to take a larger scientific party than he had on the Endeavour, and angrily withdrew after rows about the suitability of the accommodation on the ships selected for the new voyage. The hastily nominated substitute as natural historian was Johann Reinhold Forster, a polymath even by Enlightenment standards, who turned out to be both a brilliant observer and a difficult and contentious character, during and after the voyage.

Though Forster avidly collected natural specimens, he was intensely interested in the Pacific peoples encountered over the three years of the voyage. Cook’s method was to use the summers to search for the hypothetical continent in far southern latitudes, and he interspersed those forays with extended cruises in the Pacific tropics. He sought refreshment at places he had previously visited, including Tahiti and New Zealand; he investigated the situations of islands identified by earlier mariners; and he came upon other islands previously unknown to Europeans. Some visits were brief, others extended, and some repeated: the Europeans would visit Society Islanders twice and at length, and the people of Queen Charlotte Sound three times, as well as meeting, for the first time, people in Vanuatu and New Caledonia among other islands and archipelagos.

From the Admiralty’s perspective, the second voyage’s findings were negative: there was no great south land other than what might lie beyond ice, and certainly no land that offered produce or trade. But for an empirical philosopher like Forster the wealth of discovery was extraordinary. He was prompted to write a 600-page book of “observations” made during the voyage, the bulk of which reflected on “manners and customs.” He painstakingly detailed the behaviour, the institutions and the social condition of the various peoples the mariners encountered. He was particularly interested in the condition of women, especially in places like Tahiti, where they were evidently of high status and influential in political affairs. Separately, he wrote the first extended essay about the moai, the great ancestral statues of Rapa Nui. That manuscript was lost in a Polish library until just a few years ago, reflecting the extent to which Cook voyage research is not done and dusted: even now, new material continues to be found.

Forster’s intense curiosity regarding practices that were for him exotic, and the sheer variety of Islanders’ lives, was fully reciprocated by Pacific peoples. Some, like Indigenous Australians, were indeed cautious, and sought to avoid intruders, or at least maintain distance. But across Polynesia, local people, and particularly local people of high status, were eagerly interested in understanding these visitors from beyond the known universe, who came in great ships, bearing extraordinary things. Islanders keenly traded for fabrics, not least because Indigenous forms of beaten and woven cloth were of exceptional importance in their own regimes of value. The Tahitian chief Pomare, among many others, not only wanted novel things, but relationships. He understood that Cook was King George’s emissary, and presented the mariner with gifts for his sovereign. He wanted to extend the alliances he already had with the chiefs of other islands by embracing Peretania, as Britain was rendered in Tahitian.

In the Pacific, the decade of Cook’s voyages was thus an extraordinary time. The mariners’ encounters with Islanders were sometimes tense, there were misunderstandings and moments of violence. Yet there were also sustained diplomatic interactions, and much generosity. People revealed new worlds to each other; Europeans discovered Islanders, and Islanders discovered Europeans; Islanders also rediscovered each other, in the sense that Society Islanders and Māori joined Cook’s ships and visited other parts of the Pacific, encountering peoples to whom they were ancestrally related. One, Mai (generally known as Omai), also travelled to Britain, a precursor of many Pacific Islanders who visited Europe early in the nineteenth century.

Over the last twenty or so years, new scholarship focused on Indigenous perspectives has revealed and explored local experiences of these encounters. Extraordinary work by Indigenous artists has made the diversity of these perspectives and experiences public and prominent for the first time.

The decade from 2018 onwards has been and will be marked by a series of 250th Cook anniversaries, from that of the Endeavour’s departure from England through first contacts in New Zealand and Australia and other events of Cook’s second and third voyages to the anniversary, on 14 February 2029, of his death at Kealakekua Bay. These events seem defined less by the rich, unpredictable and difficult world of the voyages themselves and more by the long history of commemoration and argument about Cook. The little life itself is typically eclipsed by successive afterlives, pageants and re-enactments.

In the early twentieth century, Sir Joseph Carruthers, premier of New South Wales in the years after Federation, was an ardent Cook champion, advocating Cook statues and memorials in London and Hawaii and playing a key role in the dedication of the Kurnell landing area as a national park. Carruthers’s conservative historical imagination was challenged by writers on the left, one of whom, D. Healy, felt it important to contribute an essay on Cook’s death to the Communist, a Sydney journal “for the theory and practice of Marxism.” There was “something fascinating,” he noted, in the story of “an empire-builder who was actually worshipped by a primitive people but made the fatal mistake of being found out.” “No more than the usual arrogant, harsh and stupid British naval commander,” briefly misrecognised as a deity by the Hawaiians, Cook then died in a banal confrontation. The explorer’s death might prefigure a wider modern demystification of false gods, Healy hoped.

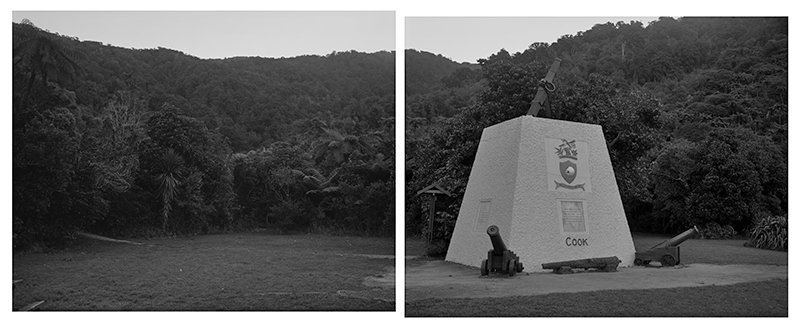

Mark Adams’s Cook Memorial, taken at Meretoto-Ship Cove, Totaranui-Queen Charlotte Sound, New Zealand. Silver gelatin prints. Courtesy of the artist

Debate of this kind periodically resurfaced. At the time of the 1970 anniversary there was growing awareness of just how damaging European settlement had been for Aboriginal people. Yet the tenor of events was nevertheless essentially celebratory. That mood has since been shaken repeatedly by war, economic challenges, environmental crises and acrimonious debate about nationality and immigration.

A consequence of an increasingly polarised politics has been much controversy about the global order’s antecedents. Some historians have sought to rehabilitate empire, suggesting that colonial rule broke up old hierarchies and hegemonies and brought the benefits of modernisation. From another direction, the legacies of slavery and other forms of oppression have been denounced by a new generation of anticolonial activists, exemplified by the “Rhodes must fall” campaigns, which sought (successfully in Cape Town, unsuccessfully in Oxford) to have statues of Cecil Rhodes removed from university precincts. In both Australia and New Zealand, monuments to “Captain Crook” are occasionally vandalised.

Cook’s own writings from the voyages make it evident that the morality of cross-cultural contact was a problem at the time. Cook was conscious of the legacies of his expeditions and was deeply troubled by the deleterious impact of sexual traffic on the health of Indigenous populations. Referring to sexual contact between sailors and local women, he wrote “I allow it because I cannot prevent it.” He was still more disturbed by the fact that the mariners’ demands appeared to have motivated Māori men to make prostitutes of their women. He feared that the trade in goods introduced new wants, and hence disease, and served “only to disturb that happy tranquility they and their Fore fathers had injoy’d.”

Cook extrapolated these reservations globally, to the whole business of European colonisation: “If any one denies the truth of this assertion, let him tell me what the Natives of the whole extent of America have gained by the commerce they have had with Europeans.” Early in his naval career, Cook had met dispossessed Beothuk of Newfoundland: he knew what he was talking about.

Among the many ramifications of the Covid-19 pandemic has been the cancellation of commemorative events associated with Cook’s arrival at Kamay. No doubt the messages offered would have been more reflective and representative than those foisted on schoolchildren such as me in 1970. But celebration, anti-celebration and even commemoration that aspires to cultural balance will inevitably diminish the rich mess of encounter, exchange, novelty, violence and moral murk that Islanders and mariners contributed to and suffered through the 1770s.

Community members studying artefacts collected during Cook’s 1769 visit to Turanganui-a-kiwa, at the Tairawhiti Museum, Gisborne, New Zealand, in September 2019. Courtesy Tairawhiti Museum

There is another story altogether. Things that people invent can, over time, assume absolutely different values from those that motivated their creation. During the Endeavour voyage, Joseph Banks, James Cook and others made extensive collections not only of natural specimens but also of Indigenous works of art and artefacts. The material they gathered, mainly through gift exchange, constituted the very first such collection to be systematically made, documented and subsequently deposited in museums.

Whatever values the Endeavour collections have had in academic, historical and artistic terms, they are unambiguously now cultural resources of unique significance. They exemplify Indigenous life and Indigenous culture; they include implements that reflect day-to-day subsistence, and art forms associated with genealogy, sanctity and ritual. They amount to material archives of sustainable ways of life. They bear the hands and values of ancestors.

To be sure, we could just cancel Cook. But the commemorative programs in New Zealand and Australia have provided occasions for artefacts to be returned for extended exhibition, on a model very different from those of standard museum loans. In Gisborne — near the sites of first contact between Cook and Māori in October 1769 — taonga, ancestral treasures normally cared for in Cambridge, were taken from the airport to the local tribal meeting house, where they were blessed, handled and deployed in performance by community members. Prior to the opening of Tu te Whaihanga, an exhibition at the Tairawhiti Museum, a series of community study visits took place, enabling descendants of the people who traded artefacts with members of the Endeavour’s crew to engage more intimately with the historical pieces. Ahead of the event, elder and artist Steve Gibbs looked forward to being able “to honour our ancestors by bringing back something very special to us all here at Turanganui-a-kiwa.”

In Australia, at the National Museum in Canberra, the spears appropriated by Cook 250 years ago are exhibited alongside a set made recently by Dharawal man Rod Mason. “The most important thing,” he has said, “is our connection to the things like the spears, that were taken from Botany Bay, and how we’re still making spears today — no one can take that away from us, because we’ve been doing it all our lives.” Shayne Williams from the Aboriginal community at La Perouse adds, “It makes me feel proud to see those spears from 1770. They are extremely valuable, not just for us at Botany Bay but for Aboriginal people right across the nation.” •