On 28 April treasurer Scott Morrison announced a $50 million upgrade of the visitors’ centre at the Captain Cook memorial on the shores of Sydney’s Botany Bay, together with $3 million in funding for new monument. Funds were duly set aside in the federal budget just a few weeks later. The site, he said, would become “a place of commemoration and recognition and understanding of two cultures, and the incredible Captain Cook.” A day before the treasurer’s announcement, the British Library’s impressive Captain Cook: The Voyages exhibition opened in London.

That the figure of James Cook (1728–79) should feature simultaneously, and so prominently, in two different hemispheres — joined, it’s true, by more than 200 years of colonial history — is powerful testament to a legacy that has been vigorously debated not only in Australia but also in other places where his shadow still falls: in Canada, New Zealand and a succession of Pacific islands from Tonga to Fiji to Hawaii.

Through much of Australia’s modern history, Cook was the archetypal “hero of Empire,” the very embodiment of civilised British virtues. His “discovery” of the eastern coast of the continent is still widely regarded as the founding moment of the modern Australian nation. But his legacy has been clouded by a reconsideration of the violence perpetrated on Indigenous peoples, not only during the voyages themselves, but also during the process of colonisation after he took possession of Australia on 22 August 1770.

The first of those two views of Cook was captured in the early twentieth century in E. Phillips Fox’s imagining of his landing at Botany Bay (above); the second can be seen in Daniel Boyd’s reworking of that image in We Call Them Pirates Out Here, painted just over a century later. Both are on display at the British Library in an exhibition that valiantly ventures beyond the dichotomy they encapsulate. What the library’s curators attempt to offer — using an enormous array of documents, artefacts, maps, videos and other installations — is a more complicated appraisal of the man in his historical context.

Viewing this exhibition as an Australian is both a privilege and a provocation. Cook is not a figure towards whom indifference is possible; but nor is he someone whose legacy we should let be plundered for political purposes. Like all treasurers, Scott Morrison is accused of cooking the books for political advantage; the metaphor is apt here, as our evaluation of the man and the figure of James Cook is subject to another kind of cooking the books.

At the behest of both the British Admiralty and the Royal Society, James Cook undertook three voyages to the Pacific Ocean, first as Lieutenant James Cook aboard the Endeavour in 1768–71, and later as Captain James Cook in command of the Resolution and Discovery in 1772–75 and 1776–80. The voyages were remarkable feats in their way, arduous and exacting, involving years away from the comforts of home amid storms at sea, towering icebergs in the far southern latitudes, and near shipwreck off the Australian coast. The toll was enormous. Disease, bad food, and the physical rigours of voyaging meant that many were never to return. By the time of his final voyage, Cook was worn down by the pressures of command, a punishing workload and illness, fated to be killed in a confrontation with Hawaiian islanders.

Using the words of Cook’s own journals and the writings of the naturalists who accompanied the voyages, the exhibition curators seek to do justice to both the geostrategic and the scientific purposes of the expeditions by showing us how its members interpreted oceans, lands and peoples previously (largely) unknown in Europe. Aboard the Endeavour were Joseph Banks, gentleman botanist and later president of the Royal Society, and Daniel Solander, a favoured former student of the great Swedish botanist and natural historian Carl Linnaeus. Father-and-son German naturalists Johann Reinhold and Georg Forster travelled on Cook’s second expedition. Other naturalists on the various expeditions included the Swedish naturalist (and another former pupil of Linnaeus) Anders Sparrman, and the Scottish surgeon and naturalist William Anderson, neither of whom, sadly, feature much in this exhibition.

The expeditions were partly the product of the Enlightenment. That renovation of European intellectual, artistic, scientific and religious endeavours gave rise to the agricultural and industrial revolutions, economic and cultural globalisation, unprecedented movements of population, and new patterns of global encounter and exchange. The Enlightenment was also entangled with Europe’s slave trade and its eventual abolition, and it played host to the first conflict that can genuinely be considered a world war (the Seven Years’ War), which reached into all theatres of European imperial rivalry, including the Americas, the Caribbean, the Indian Ocean, the Philippines and India. It was this conflict that gave the young Cook his first commission, enabling him to display his talents as mathematician and cartographer as part of Britain’s conquest of the French colony in Canada.

From France and Sweden to Scotland and Germany, intellectuals engaged in the task of reconstructing and reordering knowledge, not just of nature but of society, history and humanity itself. Cook’s voyages were inspired by efforts to investigate and to catalogue the world, and the voyages themselves (and the works they inspired) became favoured sources of data and matters of debate among intellectuals who never left Europe.

In anticipation of their significance, all three expeditions were accompanied by naturalists, botanists and astronomers. Each was expected to observe, record and write about what he saw and heard and learned, and to communicate these findings to an eager public. The artists who accompanied the three expeditions all worked under trying conditions. Alexander Buchan, Herman Sporing and Sydney Parkinson, each of whom travelled aboard the Endeavour, were botanical illustrators who soon found themselves painting landscapes and even portraits inspired by the scenes and the people they beheld. The expedition also claimed their lives, first Buchan’s and then Sporing’s and Parkinson’s, but not before they had created a rich record of cross-cultural encounters.

The formally trained professional artists who accompanied the second and third Cook expeditions were more fortunate. William Hodges (Resolution, 1772–75) and John Webber (Resolution, 1776–80) each left a considerable body of accomplished images, often framed by dramatically rendered scenery or classically posed figures that echoed the neoclassical sensibilities of the period. They also amplified a more overtly propagandistic image of Cook the peace-maker and Cook the civiliser, benevolently spreading Britain’s Empire. Both men also produced arresting portraits and social scenes that provided the ethnographic insights for which there was an insatiable appetite in Europe.

A Canoe of Tongatapu by William Hodges, 1774. British Library

The exhibition presents a great variety of images — landscapes, seascapes, portraits, botanical illustrations, drawings, paintings and sketches — some of which reveal the artists’ attempts to work out exactly what it was they were seeing. In Parkinson’s sketch of a kangaroo, for instance — the first known European drawing of the marsupial — we can see on the paper a rapid search for the right lines, the correct bulk and heft.

Inevitably, the magnificence of Hodges’s dramatic scenes and the humanity of his intimate portraits make the most vivid impression. A high point of the exhibition is the pairing of Hodges’s preparatory sketches and portraits with finished works such as his large painted cartoon of the Tahitian war fleet. These images, surely difficult to execute aboard the ship, would serve as preparatory sketches for paintings to be finished back in London.

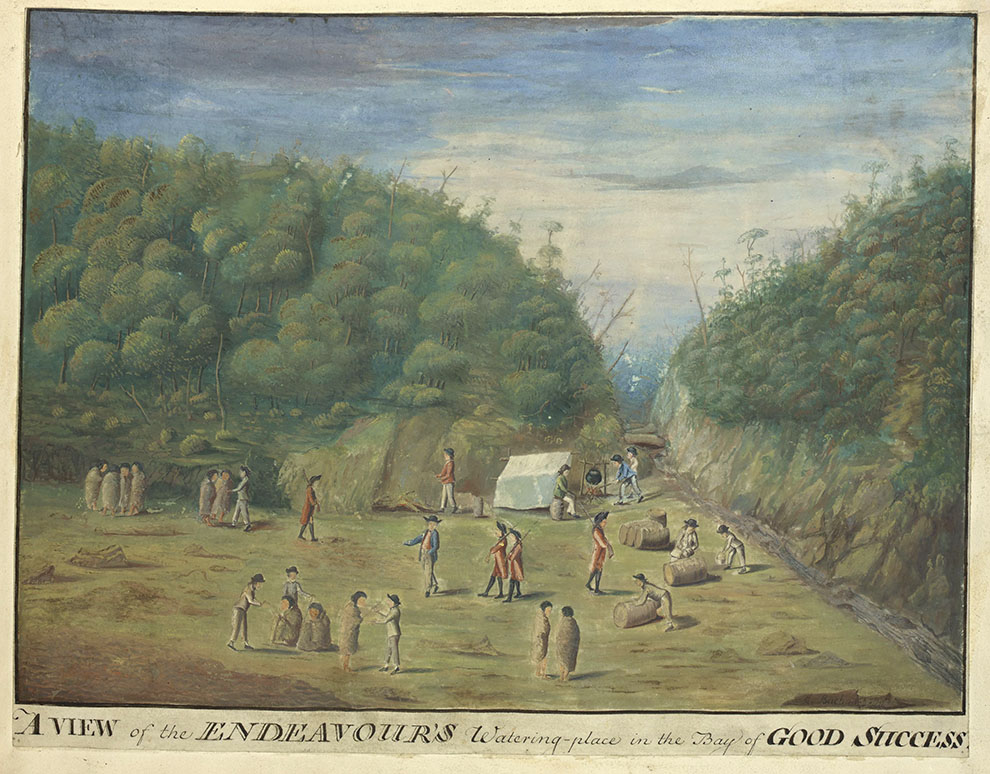

By contrast, scenes from the earlier voyage — Buchan’s depiction of the interaction between Cook’s crew and a group of Tierra del Fuegan people at the A View of the Endeavour’s Watering Place in the Bay of Good Success (below) and Parkinson’s curious image of a New Zealand War Canoe Bidding Defiance to the Ship — are less stagey and self-conscious records of encounter. Buchan seems to show the prosaic search for communication in trade. Parkinson’s image is more of a mystery. His journal, like those of Cook and Banks, testified to complex encounters between British and Māori, in both eager trade and loud defiance. But what did he depict in this image? This is no haka. Was the botanical artist trying things out again, searching for the forms and rhythm of the scene?

A View of the Endeavour’s Watering Place in the Bay of Good Success by Alexander Buchan, 1769. British Library

The encounters with Indigenous people were often charged with tension and mutual incomprehension. They could end in violence, though frequently a more peaceful exchange of goods and of information took place. The curators of Captain Cook: The Voyages want to make us aware of how the travellers sought to understand peoples so different from themselves, and how they earnestly tried to convey their humanity to audiences at home, there to be reinterpreted by other writers and artists. In the process, the distorted lens of colonial travel and observation was further distorted by a range of factors, from ignorance to arrogance and from prurience to commercial interest. To its credit, the exhibition challenges the distorted lens through which episodes of violent contact were viewed, and especially the accusations of cannibalism made in Aotearoa/New Zealand.

Arguably the most potent case of a distorted lens was the depiction of the death of Cook himself. The circumstances are hazy and the eyewitness accounts vary. The bald facts are that, having spent a month peacefully in Hawaii in 1779, the Resolution and Discovery departed amid signs the islanders were sorry to see them go. Was the departure regretted because ties with the Europeans provided the islanders with access to prestige and knowledge of use to them in island politics? Was Cook’s departure mourned because his arrival had coincided with the harvest festival of Makihiki, and he regarded as the personification of the god Lono?

Whatever the case, when the Resolution returned to Kealakekua Bay a few days later, after breaking its foremast, the islanders were tense. Quarrels and arguments broke out, and the travellers described the islanders’ behaviour as “insolent.” When Cook attempted to assert his authority by marching through the town with his armed marines and seizing King Kalaniʻōpuʻu-a-Kaiamamao, an angry crowd gathered. Stones were thrown, and Cook was hit. He fell, and was clubbed and stabbed to death in the crowd. Guns were fired. Four marines were also killed, and two wounded. Cook’s body was taken by the islanders and disembowelled, the flesh baked off the bones in accordance with islander funerary practices. Some of the remains were eventually returned to the distraught crew for burial at sea.

Whether or not Cook had been deified by the islanders, news of his death led to his European deification, or apotheosis. Omai: Or, a Trip Round the World, a play produced in 1785, culminated in the figure of Cook rising heavenward above the island, borne aloft by the figures of Fame, blowing her trumpets to the ages, and Britannia, the female embodiment of Britain’s national and imperial identity. The island and ocean he did so much to chart and claim recedes beneath his ascent, inviting other Britons to follow in his wake. The image of the apotheosis was based on a drawing by Webber, and the shipboard artist was front and centre in the myth-making. James Cook the man would become Captain Cook the imperial icon.

The exhibition uses the death of Cook as an opportunity to explore the unreliability of eyewitness reports and the shifting tropes of representation. The small selection of images depicting Cook’s death includes Webber’s, which appears to show a peaceful Cook — arm extended to dissuade his marines from firing — about to be stabbed by sinister, crowding islanders. Webber, who was on board the ship that day, would not have seen the events close up, but his image appeared to provide a powerful verification of European assumptions about islander savagery.

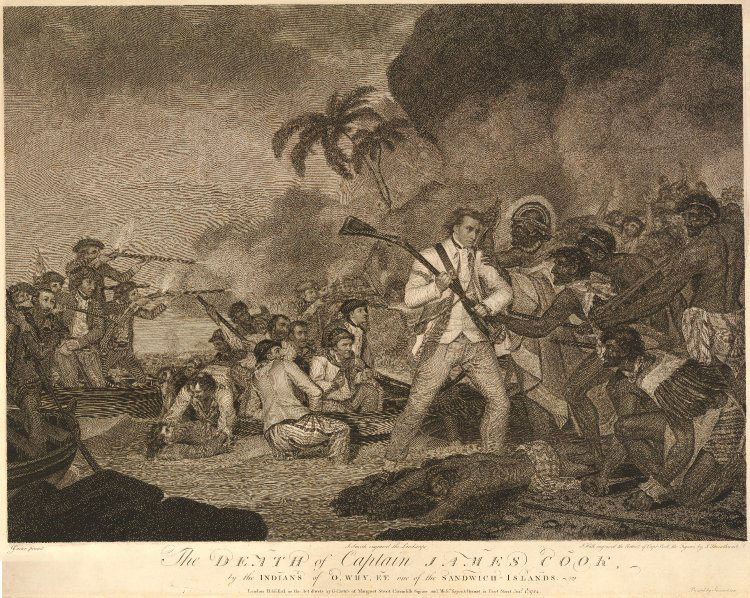

Other artists used Cook’s death as a subject for grand historical drama. In George Carter’s 1783 Death of Captain James Cook (below, but not in the exhibition), violence on both sides is emphasised, and Cook himself is implicated, his musket raised as if to club assailants who are imagined as very dark-skinned and sinister. In Johann Zoffany’s unfinished painting of 1795, The Death of Captain James Cook (also below and not in the exhibition), the islanders are used to epitomise “savagery” in muscular, neoclassical forms, hinting that these were people, like Europe’s ancient Greeks and Romans, of another, less civilised age.

Death of Captain James Cook, George Carter, 1783. British Museum

The Death of Captain James Cook, Johann Zoffany, 1795. Royal Museums Greenwich

Whose savagery? Which civilisation? What benevolence? Why violence? The voyages raise so many intersecting questions, amplified by a visual legacy that includes the meticulous maps and charts that Cook himself produced. Visitors to the exhibition are shown how science and art, mathematics and emotions, knowledge and ignorance were all decisively intertwined, bequeathing a compelling and complicated legacy.

That legacy is entwined with the mantle of “discovery.” Cook’s expeditions encountered peoples who were in no sense in need of “discovery.” The Pacific had been voyaged across and its islands populated hundreds of years before the arrival of Cook and the other European travellers who preceded and followed him.

The curators of Captain Cook: The Voyages have striven to represent Indigenous agency and register their orders of knowledge. They draw attention to the Tahitian islander Tupaia, who (with his companion Taiata) accompanied Cook for part of the Endeavour voyage. (He would die in Batavia, or modern Jakarta.) Not only did Tupaia leave images indicating how he saw these newcomers and others along the way, he also provided vital information about local Pacific islander geography and languages. Cook valued his knowledge even as he appropriated it in his own maps and charts.

Banks and a Maori, Tupaia, 1769. British Library

On the Resolution voyage, the Ra’iatean islander Mai (Omai) accompanied Cook all the way home to Britain, where he became, to Cook’s chagrin, a social sensation. But Cook was annoyed by more than Mai’s fame: he had been embarrassed by the Admiralty’s publication of his own journals from the Endeavour expedition, prepared by a professional writer, John Hawkesworth. These editions, beautifully produced in bound volumes with accompanying maps and engravings, sold like hot cakes. The suggested sexual improprieties of Banks with the Tahitian “Queen” Purea (Oberea) sparked ridicule. (Cook, who was scrupulous in such matters, had good reason to fear unregulated sexual relations between his crew and islanders; they could easily lead to tension and bloodshed, as they had on Captain Wallis’s voyage to Tahiti aboard the Dolphin in 1767.)

Further controversy — this time over which imperial nation was responsible for spreading venereal disease among the islanders — would erupt in the pages of published accounts of Cook’s expedition and in contemporaneous publications based on the French expedition under Louis Antoine de Bougainville.

The exhibition doesn’t avoid uncomfortable truths about colonial encounters in the Pacific. But it prefers to dwell on perceptions: who was looking at whom, and what did they see? Through Tupaia’s images, and through William Parry’s portrait of Mai with Banks and Solander, it allows us to see the moment of “discovery” from the other side. Colonial encounters were moments of seeing that were seen; the discovery was mirrored. One arresting image in the exhibition is Tupaia’s sketch of Indigenous Australians — people he and other Pacific islanders had not (to our knowledge) ever encountered before — fishing from their canoes. Who discovered whom here?

This is a reminder that it is time, finally, to retire “discovery” from the vocabulary that for so long framed Cook’s expeditions. It is like a mantle of lead, cast over Cook’s shoulders, bearing the impression of Empire. It’s no wonder that the human has sunk beneath the waves without trace, leaving only monuments in his place.

Monuments of empire cast long shadows, and Australians should be willing to cast more light into the gloom to see what the shadows conceal. In 1768, the British believed that Cook’s expedition would cast its own new light of knowledge. Aboard the Endeavour, Banks and Solander, working in conjunction with the illustrators who accompanied them — Sporing, Parkinson and Buchan — undertook an enormous amount of botanical work. Among them they collected, catalogued and illustrated 110 plant genera previously unknown in Europe and 1300 new species.

The ostensible purpose of the voyage, though, was not botany but astronomy. Cook was instructed to observe the Transit of Venus, which offered an opportunity to map the path of the planet between the Earth and the Sun. The calculations involved were not only of scientific interest, but also promised significant advantages in navigation. That the British should be so interested in better navigating an expanse of ocean still largely unknown to Europeans spoke of their rapid rise to global imperial status. It is therefore highly significant that Cook was also instructed, having completed the observation from Tahiti, to proceed south and to “discover,” chart and take possession — “with the consent of the natives” — of the presumed vast southern continent, Terra Australis Incognita.

It is his compliance with those orders that still divides Australians to this day. By his act of possession, he turned Terra Australis into British imperial territory and, as some see it, created the lie that this could be done because that territory was also a terra nullius, an empty, unpossessed, unowned land. In reality, he did no such thing. The characterisation is simply too crude. At no point did Cook declare or assume that Australia was a terra nullius. Indeed, he famously expressed his own misgivings about the imperial quest on which he was embarked (others, such as William Anderson, gave voice to more strident criticism).

Nonetheless, it was Cook’s Endeavour voyage that facilitated (and Banks and others who avidly promoted) the colonisation of Australia. Cook’s second and third expeditions also consolidated British claims and ambitions against other rival European imperial powers (notably France, Spain and Russia) on the northwest coast of Canada, in the central Pacific and in Aotearoa/New Zealand. He did this not just by raising flags and firing guns to take possession of various locations, memorably also by scratching out the inscription of prior Spanish claims to possession of Tahiti. He also did it by enabling the colonisation of knowledge.

The exhibition celebrates the scientific legacy of the expeditions, especially in the field of botany. Even here, though, a more critical appraisal would be welcome. In the eighteenth century, botany had become a kind of master science of European colonisation. It was a means to render known the untapped potentials of nature, to map landscapes, and to appropriate local knowledge in the authoritative cadences of scientific credibility. Colonial travel and exploration were the means whereby new catalogues of plants and new possibilities for harnessing their potential could be exploited.

It was for this reason that Solander and Banks accompanied Cook aboard the Endeavour in 1768–70. By ambitiously botanising at each and every port of call, they were claiming new ground for European knowledge, just as Cook was claiming seas and territories for Britain’s Empire. Both claims were a form of colonisation, extending a new dispensation that echoed in new names for places and for plants, where they presumed no prior names should remain. To botanise was to give purpose to colonisation by collating and curating the means to turn “wasteland” into Empire. To collect and catalogue plants on new shores was to botanise in terra nullius.

The exhibition allows us to see how intimately scientific activities were interwoven with colonial aspiration. Cook’s own journals from the expedition attest that Banks and Solander were direct participants in the key moments of colonial contact throughout the expedition. When the two men ventured ashore, as they did at every opportunity, they collected and catalogued as many plants as they could find. In 1768, at Tierra Del Fuego, they became lost gathering plants on shore and almost died from exposure to the extreme cold. (Two of Banks’s servants actually did die.) The following year, on Tahiti, Solander assisted Cook in making his important astronomical observations, and was also an unwitting subject of the islanders’ efforts to acquire the sacred prestige of the newcomers by picking their pockets, in his case depriving him of his spyglass. As unfortunate as that sounds, it was not as bad as the theft of Captain Cook’s stockings one night from under his very head.

Later that year, on Aotearoa/New Zealand, Solander accompanied Cook and Banks on their first landing and meeting with the Māori. And in Australia on 29 April 1770, he again accompanied Cook and Banks on their first encounter with Indigenous Australians. It was an inauspicious meeting: the Indigenous warriors they saw on the beach all ran off at the sight of the boat coming ashore. Cook and his party resolved, Cook wrote, to “throw them some nails, beads, etc., a shore, which they took up, and seem’d not ill pleased with, in so much that I thought that they beckon’d to us to come ashore; but in this we were mistaken, for as soon as we put the boat in they again came to oppose us, upon which I fir’d a musquet…” They threw a spear in reply. Cook then fired “a Second Musquet, load with small Shott,” which hit one of the warriors.

It was in this way that the colonisation of Australia began: with misunderstanding, shouted threats, thrown objects, and gunfire. Banks and Solander were there again at another and even more telling incident on 22 August 1770. On this day, at a place forever since named Possession Island, Cook recorded:

I landed with a party of men, accompanied by Mr. Banks and Dr. Solander… Having satisfied myself… [that] from the Latitude of 38 degrees South down to this place, I am confident, was never seen or Visited by any European before us… I now once More hoisted English Colours, and in the Name of His Majesty King George the Third took possession of the whole Eastern coast from the above Latitude down to this place by the Name of New Wales, together with all the Bays, Harbours, Rivers, and Islands, situated upon the said Coast; after which we fired 3 Volleys of small Arms, which were answer’d by the like number from the Ship.

This was a moment of profound significance in Australia’s recent history. Despite the continuous 60,000-year (or more) inhabitation of the land by a people rich in culture and knowledge, subjects of laws and of lore since time out of mind, as fully in possession of themselves as it is possible for a people to be, by this simple act of possession they and the land on which they lived became subject to another’s ownership. Australia, from Cook’s act of possession forward, was to be irrevocably colonised.

In the early days after Federation in 1901, Captain Cook was a useful symbol to reassert British identity and imperial belonging. In his reimagined majesty he became the semi-divine presence invoked in statuary and art — an anaesthetising balm for a hapless nation of arriviste white-skinned ex-colonials earnest to deny the antiquity of prior inhabitation by a peoples they were engaged in supplanting, and troubled by their isolation in a region teeming with other peoples they feared would do the same to them. Cook became an image of how Australians of a particular pedigree wanted to see themselves: as bold, brave, heroic and civilised.

In 2018, Cook certainly continues to symbolise, but what exactly? Most recently his likeness in heroic bronze has intensified the dispute over the date of Australia Day (since 1988, commemorated on the anniversary of the landing of the first British convict-colonists in 1788) and the accusation that the date commemorates a colonial genocide.

The bronze relics of Australia’s colonial insecurities in the early twentieth century have attracted new commentary.

Boyd’s We Call Them Pirates Out Here, like the British Library exhibition, is a provocation to think carefully about our national symbols. Symbols are never just symbolic; they tremble with a latent power. Cook as a pirate is an image that confronts us with the reality that European colonisation was a theft, not just of land and resources but also of whole peoples’ futures. Those thefts were sanctified with laws and justified by the other peoples who inherited the theft by building their own futures.

Pirate, hero, coloniser, civiliser, scientist. Who was James Cook? The question lingers over another recent reimagining, Michael Parekowhai’s The English Channel, on display at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. A larger-than-life figure of a dejected-looking Cook, fashioned in highly polished stainless steel, it is sitting on a sculptor’s tripod and positioned to look down through a large window onto Sydney Harbour (but not Botany Bay, where he actually landed). This Cook reflects all attempts to answer that very question.

Michael Parekowhai, The English Channel, 2015.

He seems weighed down by his own legacy, and we see ourselves reflected but weirdly out of shape. We might be led to ask why we remain so convinced that the figure of Cook should bear images of ourselves.

This is not a question the British Library exhibition asks directly, but it is a question that it invites us to consider. The decision by the federal government to fund the renovation and enlargement of the memorial to Captain Cook might seem an anachronistic gesture if not for the fact that our colonial and military past has become so relentlessly politicised, mined for bullets in the pitiless war for momentary advantage, and carried on in confected tones of aggrieved and indignant pride or sentimental advocacy.

Captain Cook: The Voyages is the kind of exhibition that might provide impetus for a more complicated public appraisal of Cook. But few Australians will have the opportunity to see it, or to hear the videotaped views of Indigenous Australians, Māori, Canadians and Pacific Island peoples who have the opportunity, in the course of the exhibition, to reflect on Cook’s complicated legacy.

Not long ago, the Australian government dismissed the latest attempt by Indigenous Australians to present their own vision for the future, in the Uluru Statement from the Heart. Cook is not the appropriate avatar of Empire to embody this continued denial, but his persistent enrolment as national icon ensures that his legacy will continue to shadow the nation’s future. Would it be too much to ask that, instead of avatar or icon, hero or villain, we begin to see Cook with fresh eyes? We might then begin to see beyond him, beyond the reflection of our wished-for selves, and begin to perceive new possibilities. ●