Moneyland: Why Thieves and Crooks Now Rule the World and How to Take it Back

By Oliver Bullough | Profile Books | $39.99 | 368 pages

The rich live globally, the rest of us have borders.

— Oliver Bullough

In a parallel world, money writes its own rules. It’s the land of the super-rich: a place where the normal laws no longer apply, numbers don’t add up, and words twist into unsolvable riddles.

Oliver Bullough calls this world Moneyland. You’ve probably never been to Moneyland but you certainly know of it. Moneyland is the home of shell companies that seemingly don’t do anything but somehow make huge profits. It shelters offshore bank accounts that are owned by nobody but still benefit somebody. As if by magic, a person on a declared salary of $4000 a month can afford to buy a $35 million mansion in Malibu. Even national identities can be bought or hidden.

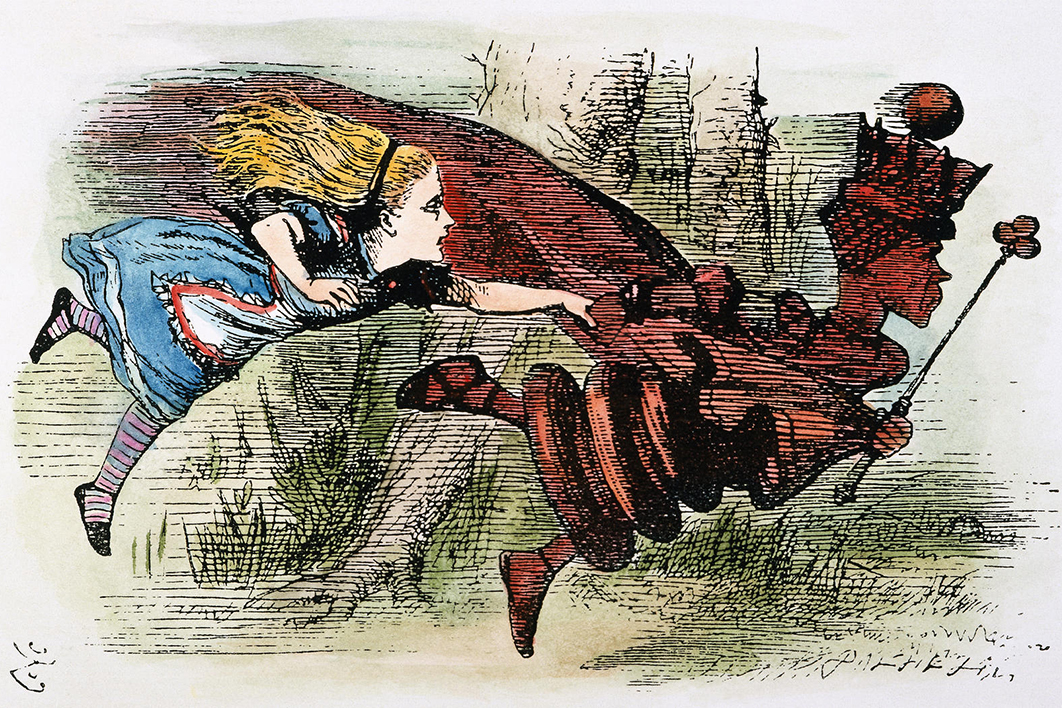

Are you ready to jump down the rabbit hole?

Bullough will be your white rabbit. Follow him and he’ll show you this surreal world and its hidden influence over your day-to-day life.

He knows the terrain well. A Russian-speaking journalist, he’s been observing the emergence of Moneyland since the fall of the Soviet Union. In those heady days, Bullough believed (along with almost everyone else in the West) that the “good guys” had won. Democracy, capitalism and globalisation promised to bring liberty and prosperity to Eastern Europe and beyond. The end of history — the final point of political, economic and social development — was nigh.

But as it turned out, history didn’t end. If anything, Bullough says, it accelerated.

When developing countries opened up to global financial markets, corrupt officials found it much easier to siphon public funds into their own pockets without anyone catching on. And because there’s profit to be made by catering to footloose international capital, financial institutions that should have known better took the money without asking where it came from.

Take Ukraine, for example. Bullough details how the country’s president, Viktor Yanukovych, made hundreds of millions of dollars from a “shadow state” operation that engaged in bribery, intimidation and fraud.

When the citizens of Ukraine revolted and threw Yanukovych out of office in 2014, they were gobsmacked by the extent of his personal wealth. His presidential palace, an enormous log cabin, was situated on a block so big it required bicycles to traverse. While living off a state salary, Yanukovych had somehow amassed countless treasures: among them, a private galleon restaurant on his lake, golden golf clubs, a private cinema, and a piano worth more than $100,000.

The bathrooms in Yanukovych’s palace even had televisions mounted on the wall at sitting height, in front of the toilets. As Bullough writes, “While Ukraine’s citizens died early, and worked hard for subsistence wages… the president had been preoccupied with ensuring his constipation didn’t impede his enjoyment of his favourite TV shows.”

Corruption is not new, especially in countries with weak democratic institutions. What has changed, Bullough says, is how effectively pilfered funds can be secreted away in the nooks and crannies of the global financial system. Corruption now takes place on a global scale.

Fraud of the state procurement system may have cost the Ukrainian government US$15 billion a year. It’s hard to say exactly where all that money went; it is exceedingly difficult to find stolen funds once they have entered the Moneyland machine. It might have flowed into Swiss bank accounts, or offshore companies (apparently) located on a tropical island in the Caribbean, or high-end London apartments seemingly owned by no one.

The trouble is that globalisation allows money to flow freely across national borders, but democratic laws stop at those boundaries. As Bullough shows time and again, the laws of Moneyland are whichever laws anywhere in the world are “most suited to those wealthy enough to afford them.”

Economic competition should lead to efficient outcomes by rewarding investors who put their money into productive activities. Everyone benefits from the economic growth and innovation that result. But that can’t happen when there’s more profit to be made in rent-seeking. By making money out of loopholes and contradictions between different countries’ tax and legal systems, or by embezzling public funds, the denizens of Moneyland divert investment into activities that don’t benefit anyone — except themselves.

Bullough couldn’t be a better guide through this strange world. Fuelled by his impeccable research, he expertly follows the trail of breadcrumbs left behind as money moves from one jurisdiction to another. He takes you from Yanukovych’s palace in Ukraine to a retired mechanic’s garage on a tropical island, to a bridal shop in Britain. The stories he tells along the way paint a picture of a broken system.

What he lacks is a solution to all this. If we agree that Moneyland is unfair and unproductive, what should we do about it? Bullough might be wearing rose-tinted glasses: at times he speaks wistfully of the Bretton Woods era after the second world war, when capital controls prevented money from flowing freely across national borders. One gets the sense he wishes the controls had never come down.

I’m not convinced that capital controls are the answer. This egg can’t be unscrambled. But the only solution I see is almost as hard: countries need to work together to protect democracies with weak institutions, and to increase transparency and prevent fraud. Ironically, that might require forfeiting some national sovereignty so that when money flows across borders, laws can too.

It won’t be easy. Like Alice, we’ll have to be brave and jump. •