On Tuesday this week, the Northern Territory quietly became the last Australian state or territory to introduce a compulsory custody notification service, or CNS, for Indigenous people arrested by police. But sources in Darwin say that the soon-to-be-introduced legislation, which requires police to notify an Aboriginal legal service of every arrest, was written by police and doesn’t go far enough to protect arrested people’s legal rights. Nor does it require police to make a notification after they take people into custody for being intoxicated in public, a scenario most at risk of resulting in a death in custody.

From 11 June, NT police are obliged to contact the North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency, or NAAJA, whenever an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person is arrested on suspicion of criminal activity. The new rule is in line with a memorandum of understanding between NAAJA and the police finalised at the end of May. But neither the memorandum nor the amendment will forbid police officers from interviewing people before contacting NAAJA. As a result, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people arrested by police could continue to give recorded interviews before they get legal advice against doing so.

Mandatory notification of an Aboriginal legal service was a recommendation of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody when it reported nearly three decades ago, in 1991. Since then, legal services have also seen CNS services as ways to advise their clients about their legal rights, such as the right to silence in the face of police questioning. This broader view of the CNS system is not typically shared by police.

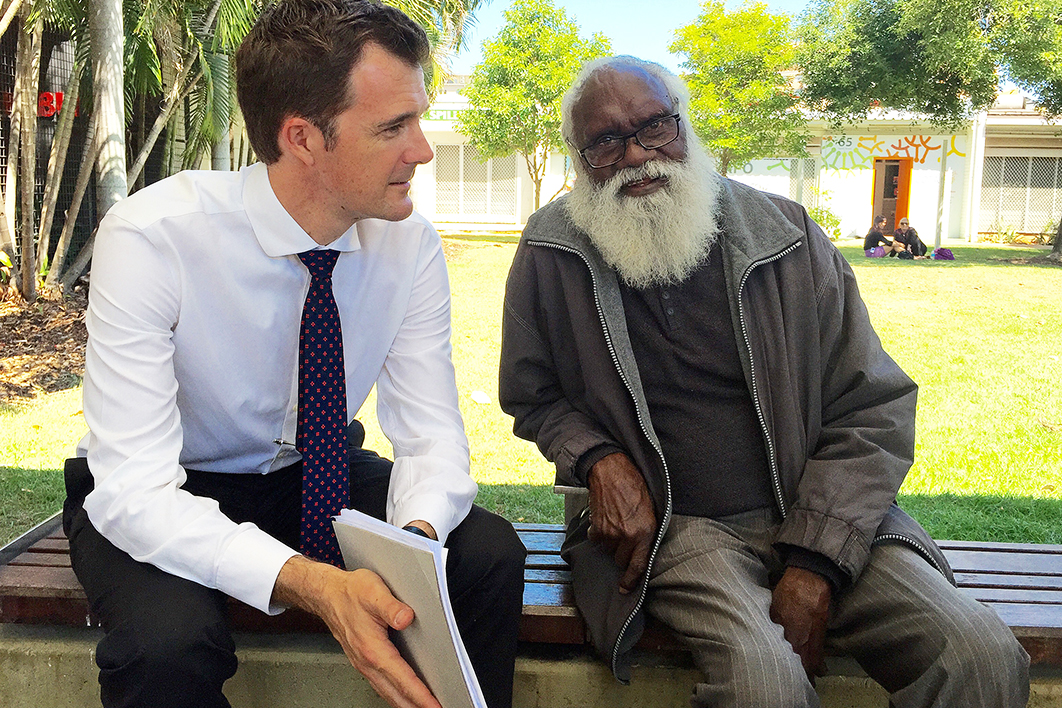

This tension between the two visions for a CNS — the narrow police vision and the broader one held by NAAJA — appears to have been behind repeated delays in its rollout following its announcement by the new chief minister, Michael Gunner, in 2016.

In October of that year, Gunner wrote to federal Indigenous affairs minister Nigel Scullion committing the Territory to a legislated CNS scheme. Scullion wrote back offering the Commonwealth’s terms: the prime minister’s department would fund a CNS for three years on condition that the NT government introduced the necessary legislation and committed to picking up the tab after the first three years. Deputy chief minister Nicole Manison, also police minister, confirmed her government’s acceptance of Scullion’s offer in December 2017.

In November last year Scullion announced $2.25 million in federal funding over three years for NAAJA to run a CNS throughout the Northern Territory. (Since it took over the Alice Springs operations of what had been the Central Australian Aboriginal Legal Aid Service in November 2017, NAAJA has been the Territory’s only Aboriginal-run legal service providing criminal defence services to Aboriginal people.)

NAAJA immediately set about recruiting staff. But it was hardly smooth sailing. Sources claim that the CNS design is flawed, and the funding agreement doesn’t provide quite enough money to run it.

NAAJA’s service won’t replicate the highly effective, nearly twenty-year-old NSW notification service, which takes Aboriginal Legal Service lawyers out of their normal court-based routines and rosters them onto phone shifts for a week at a time. Instead, it will employ entirely new staff who don’t have existing knowledge of particular police practices or of clients’ communities and likely bail options. And the new CNS team’s work will be entirely phone-based. “Like a justice call centre,” one source said.

Some of the CNS staff members at NAAJA are non-lawyers who can’t lawfully give legal advice. The federal funding appears not to be adequate to fill all CNS positions with lawyers and account for minimum after-hours loading requirements in the industry award. It is understood that when non-lawyers take custody calls from police, they will be providing clients with “legal information” based on a written manual, as distinct from advice.

Despite these concerns, the CNS seemed all set to begin operations by a March 2019 deadline. But the Gunner government’s promised legislation failed to materialise. Rumours began circulating that NT police were holding out on a CNS design agreement. The office of the police commissioner, Reece Kershaw, has not responded to interview requests for this article, but sources close to police have suggested this was the case.

In a 7 March statement obviously motivated partly by political concerns in the lead-up to the federal election, Scullion was heavily critical of what he called the “do-nothing Gunner government” and its failure to introduce CNS legislation. He said that NT police “strongly support the establishment of a CNS as a tool to also assist the police in their engagement and interactions with Indigenous Territorians.”

Kershaw, Manison and Priscilla Atkins, chief executive of NAAJA, have maintained a collective silence, and none of them commented for this article, despite requests. Behind the scenes, negotiations continued between NAAJA, Northern Territory Police and the Gunner and federal governments, resulting in the memorandum of understanding and the legislative amendment. It is understood that NAAJA was not involved in drafting the bill, and that it was written substantially by police.

A spokesperson for the prime minister’s department says that it has been working closely with the NT government to have the legislation passed, with the CNS to be governed by the NAAJA–police memorandum in the meantime. Until the amendment formally becomes law, police won’t legally be able to contact NAAJA without first getting consent from the person they’ve arrested. After it becomes law, police must contact NAAJA regardless of the arrested person’s wishes.

But in what appears a glaring omission, police may not be legally required to contact NAAJA whenever they place Aboriginal people in so-called “protective custody,” which happens often. Police can remove people from public places if they deem them too intoxicated to care for themselves. If police can’t safely leave them at home or a sobering-up shelter they can keep them in police cells overnight. Critics have long been concerned that “protective custody” is too often used to lock Aboriginal people up for no good reason, and they point to consistent research findings that show police often mistakenly assess Aboriginal people as intoxicated.

Quarantining protective custody and paperless arrests from the CNS could subvert its intent, which is to prevent Aboriginal deaths in custody. In May 2015, fifty-nine-year-old Warlpiri man Kumanjayi Langdon died in a cell inside the Darwin police watch house after police saw him drinking in Spillet Park and arrested him for the purpose of giving him a $74 fine once he’d become sober. And in January 2012, twenty-seven-year-old Kwementyaye Briscoe died in an Alice Springs police cell, where he’d been placed in protective custody. It is understood that the new CNS legislation would not have required police to contact NAAJA in either circumstance, though it is hoped these situations will be covered by the memorandum.

Across the country, more than 400 Aboriginal men, women and children have died in custody since the royal commission reported in 1991. Since New South Wales legislated its CNS in 2000, just one Aboriginal person has died while in police custody in that state. That single death, in 2016, happened after Maitland police failed to use the CNS to notify the Aboriginal Legal Service of the arrest of a thirty-six-year-old woman. Only the Australian Capital Territory has introduced similar legislation.

Police forces in other states have convinced governments to avoid legislating CNS systems in favour of provisions in police operational manuals. The Victoria Police Manual’s instruction 113-1, for instance, requires a police officer who arrests an Aboriginal person to call the Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service within an hour. Notification requirements in South Australia, Tasmania and Western Australia are similarly limited to police policy and operations documents, while Queensland’s CNS relies on a memorandum of understanding with that state’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Service. The Northern Territory will be the third jurisdiction to legislate, with Western Australia set to follow.

Until Tuesday, NT police merely had to make “reasonable efforts” to put an arrested person in touch with a lawyer — but only if the arrested person requested legal advice. Extraordinarily, police were not required to inform people of their right to speak to a lawyer. Nor were they legally obliged to use interpreters, even if the person they arrested was from a remote Aboriginal community and spoke little or no English. Interpreters aren’t mandatory under the CNS, either, but it is understood the memorandum requires police to make genuine efforts to make one available on request by either the arrested person or NAAJA.

Sources say some inside NAAJA are disappointed that the right to seek legal advice before being interviewed — and therefore the right to silence — is not explicitly protected in the CNS legislation. A January 2018 decision of the Supreme Court, upheld in March this year, means it is rarely in people’s interests to participate in a recorded interview if they’re arrested in the Northern Territory.

While CNS services reduce the likelihood of deaths in police watch houses, they can’t prevent people from dying in prisons. (Despite New South Wales’s legislated CNS, at least ten Aboriginal people have died in that state’s prisons and remand centres in the past decade alone.) Advocates and researchers agree that the underlying reasons for the proportionally high numbers of Aboriginal deaths in custody remain the same as they were during the royal commission thirty years ago: the appalling health gap between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians, and the astonishing — and growing — rate at which Aboriginal people are being locked up. •